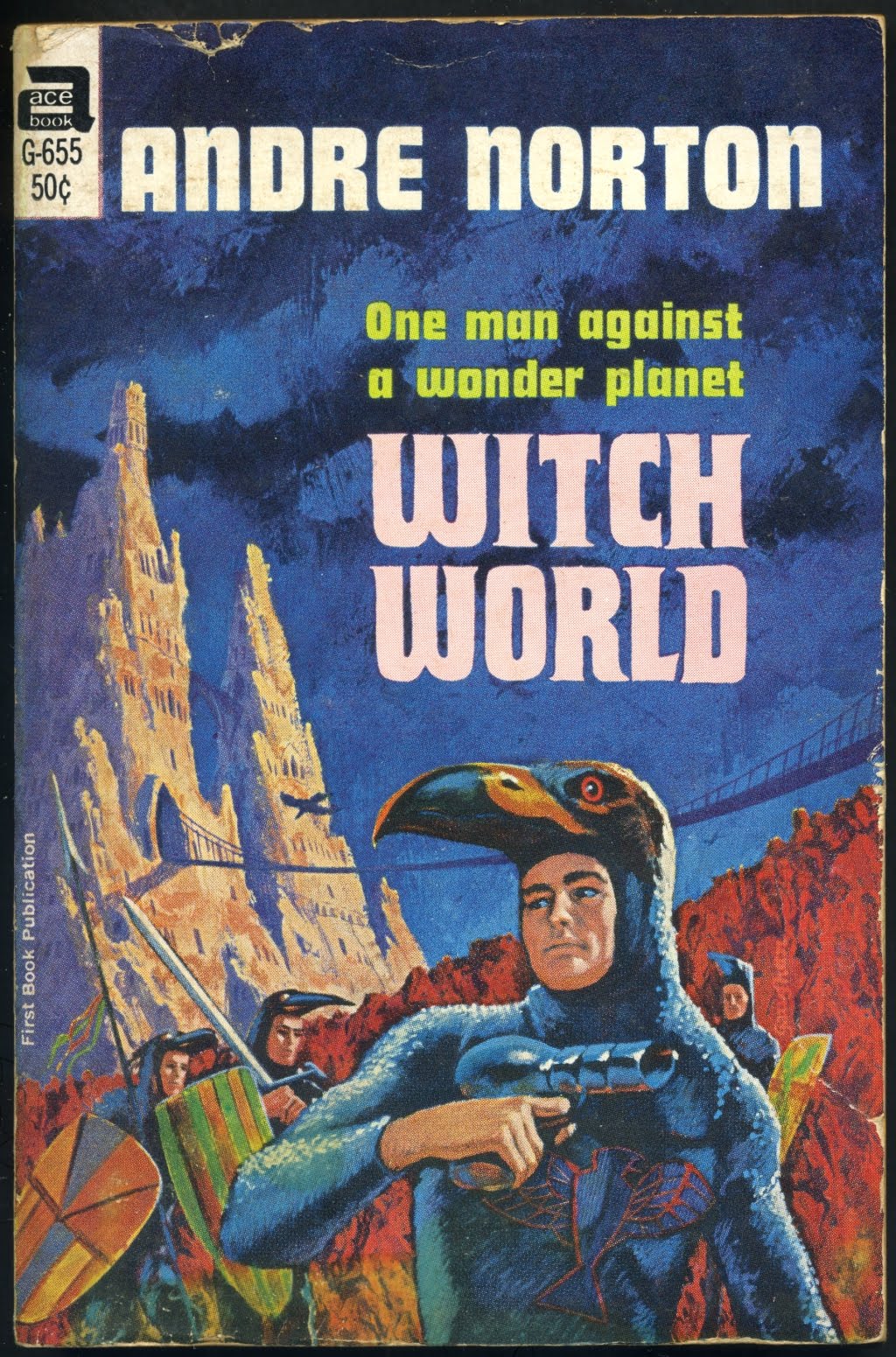

Andre Norton's YA Novels

/ When I worked at a bookstore (the now defunct Walden Books), I had a co-worker that loved Andre Norton. I'd never read any of her books throughout High School, although I was certainly familiar with her name. I wish now that I did.

When I worked at a bookstore (the now defunct Walden Books), I had a co-worker that loved Andre Norton. I'd never read any of her books throughout High School, although I was certainly familiar with her name. I wish now that I did.

Norton wrote largely for what we now call the YA audience: teenagers, with fantastical adventures throughout numerous worlds and times. She was also largely ignored or dismissed for writing 'children's literature', which is a shame, because it's likely that she had as great an influence on the shape of the modern genre as Robert Heinlein, who's Juvenile novels attracted millions of fans to new worlds. Norton was the same, and influenced countless readers and writers for decades. It's fitting that the major SF award for YA fiction is titled The Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy.

Go read Andre Norton's YA novels over on Kirkus Reviews. Sources:

- Trillion Year Spree, Brian Aldiss. Aldiss contends here that Norton was part of a growing movement in science fiction in the 1950s, along with a small core of other authors.

- Who Wrote That? Andre Norton By John Bankston. This book designed for YA readers seems to be the only Norton biography on the market right now. I used the chronology to help structure this post.

- Science Fiction, Today and Tomorrow, edited by Reginald Bretnor. Anne McCaffrey has an essay in this book that mentions Andre Norton briefly.

- The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction, Paul Allen Carter. Carter talks about Norton very briefly here in a larger context within the genre.

- Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction, by James Gunn. Norton has a couple of mentions here, talking about her work in the 1950s.

- Science Fiction after 1900, Brooks Landon. Landon's book is a great look, and he talks about Norton a couple of times in this book regarding her influence in the genre.

- The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James. This book also mentions Norton sparingly, but does so within the context of SF, Women and the 1950s.

- The Faces of Science Fiction: Intimate Portraits of the Men and Women who Shape the way we look at the future, Patti Perret. Norton has a portrait in here, where she talks about science fiction as an entertainment medium.

Web:

- Andre Norton correspondence, literary and dollhouse, Cleveland Public Library. There's some interesting letters here that talk quite a bit about Norton's character and personality.

- Obituaries: Los Angles Times and The Guardian. Both were helpful, as they provided some good (although at times, inaccurate) details about her life.

As I've been writing this column, I've realized that there's points where I have to move ahead and skip authors, or, after some reflection, research and writing, that I missed someone critical. Over the last couple of months, I've been realizing that not covering L. Frank Baum has been a drastic oversight, and that at the next available opportunity, I need to cover him and his wonderful world of Oz.

As I've been writing this column, I've realized that there's points where I have to move ahead and skip authors, or, after some reflection, research and writing, that I missed someone critical. Over the last couple of months, I've been realizing that not covering L. Frank Baum has been a drastic oversight, and that at the next available opportunity, I need to cover him and his wonderful world of Oz.

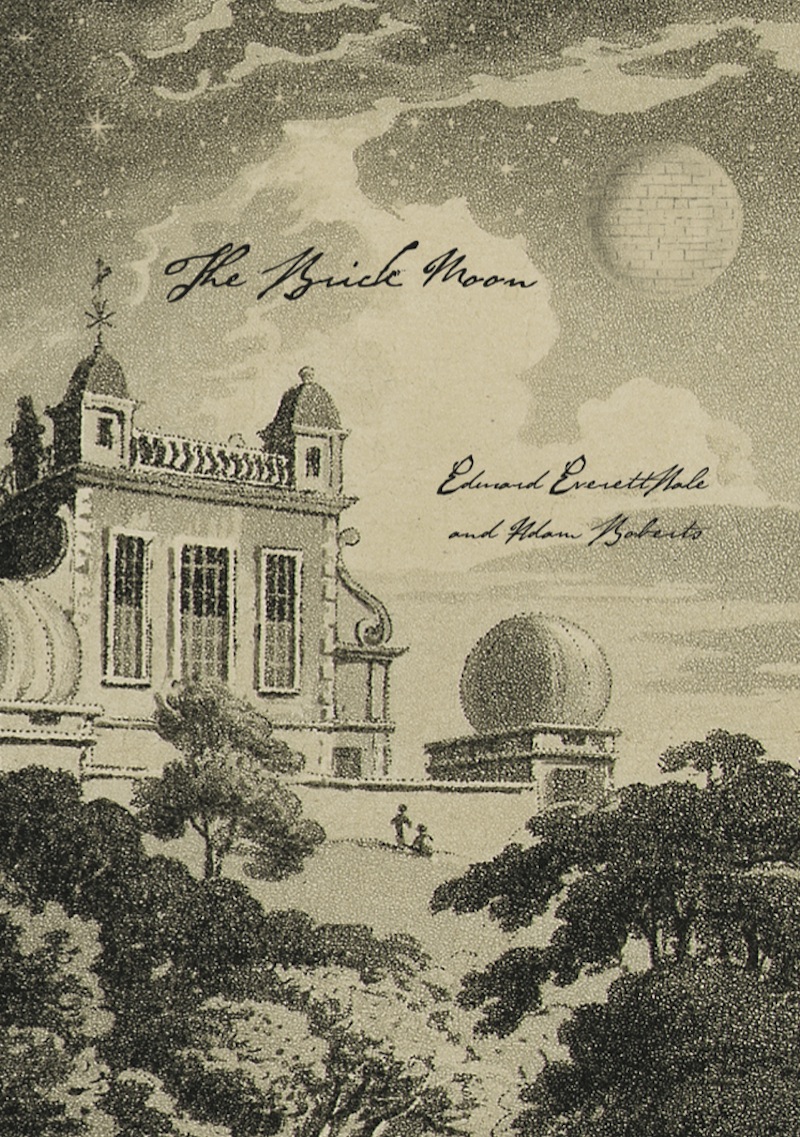

I've got a bit of a bonus installment for my column on SF History. I've got a limited amount of space that I've got to work with for Kirkus, and as such, I've had to blow past a couple of things. Fortunately, with Jurassic London's new release of The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale, I've had the opportunity to circle back and write about this particular novel.

The Brick Moon is the first science fiction story that uses the idea of an artificial satellite, and it's an excellent example of what science fiction is: extrapolation into the near future. In this instance the need for a navigational beacon in the skies. It's a cool premise, and in one fell swoop, Hale comes up with the idea for a satellite, communications satellite and space station. (Yes, Clarke came up with the idea as well. His invention is notable because it wasn't in SF, but a non-fiction speculation).

I've got a bit of a bonus installment for my column on SF History. I've got a limited amount of space that I've got to work with for Kirkus, and as such, I've had to blow past a couple of things. Fortunately, with Jurassic London's new release of The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale, I've had the opportunity to circle back and write about this particular novel.

The Brick Moon is the first science fiction story that uses the idea of an artificial satellite, and it's an excellent example of what science fiction is: extrapolation into the near future. In this instance the need for a navigational beacon in the skies. It's a cool premise, and in one fell swoop, Hale comes up with the idea for a satellite, communications satellite and space station. (Yes, Clarke came up with the idea as well. His invention is notable because it wasn't in SF, but a non-fiction speculation). I've had a passing fascination with McCaffrey's books over the years, even as I never really dabbled in them. (I owned one book, Dragonflight, years ago.) I was always somewhat intimidated by the sheer size and scale of the series, and I was always more interested in SF than I was Fantasy (although now, I realize that that was a bit misguided.) Anne McCaffrey was always an author I was aware of: one of the female authors alongside the Asimovs, Herberts and Heinleins in my high school library.

I've had a passing fascination with McCaffrey's books over the years, even as I never really dabbled in them. (I owned one book, Dragonflight, years ago.) I was always somewhat intimidated by the sheer size and scale of the series, and I was always more interested in SF than I was Fantasy (although now, I realize that that was a bit misguided.) Anne McCaffrey was always an author I was aware of: one of the female authors alongside the Asimovs, Herberts and Heinleins in my high school library. I've been a fan of Game of Thrones since I first caught it a couple of years ago, and I've been impressed with the HBO series as I've continued to watch. When Season 1 hit, I pulled out my copies of A Song of Ice and Fire and started the first book, alternatively reading and watching the show. I've found the books to be a trial to get through, but I've ultimately enjoyed them.

I've been a fan of Game of Thrones since I first caught it a couple of years ago, and I've been impressed with the HBO series as I've continued to watch. When Season 1 hit, I pulled out my copies of A Song of Ice and Fire and started the first book, alternatively reading and watching the show. I've found the books to be a trial to get through, but I've ultimately enjoyed them. In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history.

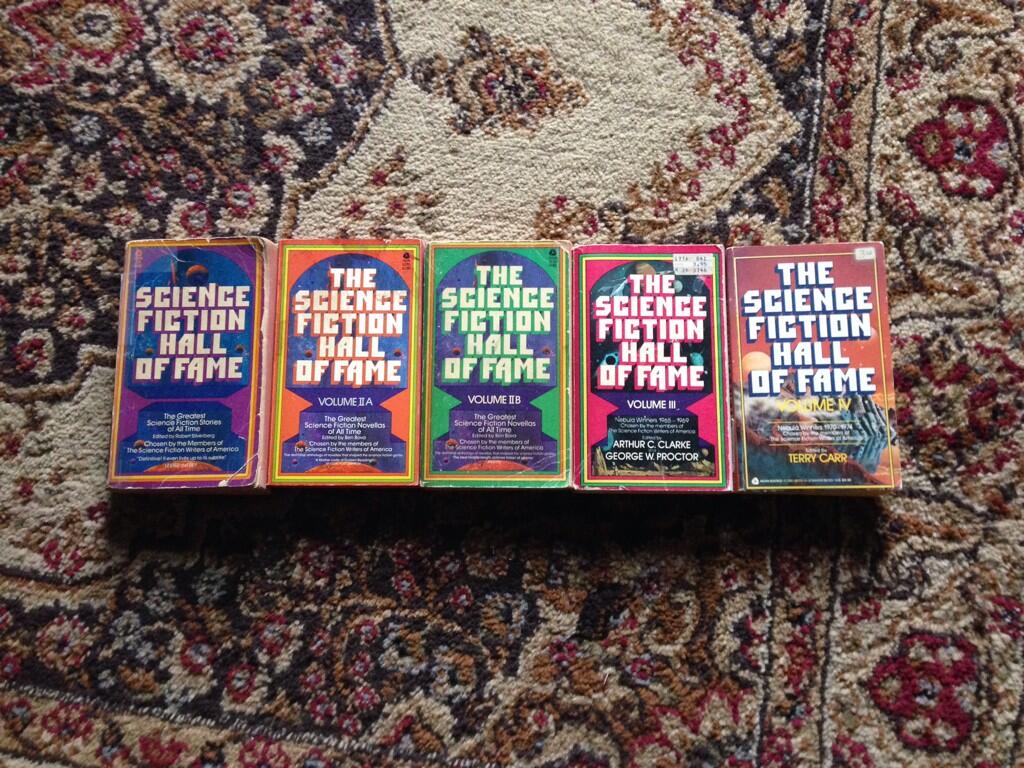

In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history. One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him.

One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him. The latest issue of

The latest issue of  When Megan and I started dating, I made the trip from Vermont to Pennsylvania. It's around eight hours, covering four states. On one such trip, I decided I really didn't want to endure New Jersey, and took an early exit off of I-87 toward the alluring sign 'Delaware Water Gap'. It didn't take me much longer to cut through the two-lane road, perfect for driving a Mini Cooper on, and it took me through a quiet, quaint looking town of Milford. Since Megan and I have married, we make the trip frequently, crossing through Milford a couple of times a year. I like the town, even though I've never stopped.

When Megan and I started dating, I made the trip from Vermont to Pennsylvania. It's around eight hours, covering four states. On one such trip, I decided I really didn't want to endure New Jersey, and took an early exit off of I-87 toward the alluring sign 'Delaware Water Gap'. It didn't take me much longer to cut through the two-lane road, perfect for driving a Mini Cooper on, and it took me through a quiet, quaint looking town of Milford. Since Megan and I have married, we make the trip frequently, crossing through Milford a couple of times a year. I like the town, even though I've never stopped. The first Blish story I read was Surface Tension in Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology. While there's certainly some issues with the anthology, it's a solid collection of short fiction. Blish isn't an author I've read extensively, but I remember him popping up frequently in the various anthologies I read over the years.

The first Blish story I read was Surface Tension in Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology. While there's certainly some issues with the anthology, it's a solid collection of short fiction. Blish isn't an author I've read extensively, but I remember him popping up frequently in the various anthologies I read over the years. There were two authors I read extensively when I first started reading science fiction. The first was Isaac Asimov, because, well. Robots. Foundation. Reasons. The other was Arthur C. Clarke. The first story I really remember reading from him came from a thick anthology cultivated by Asimov, with one fantastic story by Clarke in it: Who's There? I then ran through a bunch of his books: 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010, 2061 and 3001 are the ones I checked out over and over again. Later, I dug into Rama and even later, Childhood's End.

There were two authors I read extensively when I first started reading science fiction. The first was Isaac Asimov, because, well. Robots. Foundation. Reasons. The other was Arthur C. Clarke. The first story I really remember reading from him came from a thick anthology cultivated by Asimov, with one fantastic story by Clarke in it: Who's There? I then ran through a bunch of his books: 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010, 2061 and 3001 are the ones I checked out over and over again. Later, I dug into Rama and even later, Childhood's End.

Over the course of writing this column for Kirkus Reviews, I've found that the early women authors writing in the genre were some of the most influential, producing some incredible stories over their careers. I've looked at quite a few who were incredibly influential:

Over the course of writing this column for Kirkus Reviews, I've found that the early women authors writing in the genre were some of the most influential, producing some incredible stories over their careers. I've looked at quite a few who were incredibly influential:

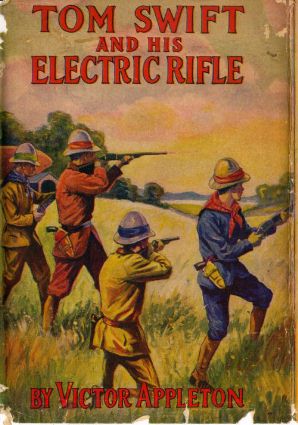

I never read the Tom Swift novels as a kid; I was always more obsessed with the Hardy Boys series. Over the years, I've read bits and pieces about Edward Stratemeyer, the man who was behind the long-running book series, as well as those of Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins (a favorite of my mother's), The Rover Boys and Tom Swift. He conceived of a character, put together a formula, and had a freelancer ghost write the novel before editing it. The process has always fascinated me, but when it came to looking into his background, an entire segment of early science fiction comes to light: the Dime Store novels, which created entire subgenres in their own right. More than that, they carried with them some real kernels of thematic material which have since propagated far into the future, which surprised and delighted me.

I never read the Tom Swift novels as a kid; I was always more obsessed with the Hardy Boys series. Over the years, I've read bits and pieces about Edward Stratemeyer, the man who was behind the long-running book series, as well as those of Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins (a favorite of my mother's), The Rover Boys and Tom Swift. He conceived of a character, put together a formula, and had a freelancer ghost write the novel before editing it. The process has always fascinated me, but when it came to looking into his background, an entire segment of early science fiction comes to light: the Dime Store novels, which created entire subgenres in their own right. More than that, they carried with them some real kernels of thematic material which have since propagated far into the future, which surprised and delighted me.

When the fall arrives, I get into the mood for darker fiction, particularly H.P. Lovecraft. I've written about Lovecraft before, but I didn't quite realize how important the magazine was, despite its general flaws in quality, to the genre. Authors such as C.L. Moore, and quite a few others passed through its pages, and it's clear that it's a publication that's just as important as Astounding or Amazing Stories.

When the fall arrives, I get into the mood for darker fiction, particularly H.P. Lovecraft. I've written about Lovecraft before, but I didn't quite realize how important the magazine was, despite its general flaws in quality, to the genre. Authors such as C.L. Moore, and quite a few others passed through its pages, and it's clear that it's a publication that's just as important as Astounding or Amazing Stories. It's fall, and I've been once again shifting from the usual topic of science fiction to horror and fantasy. Last year, I wrote about H.P. Lovecraft, and in my last column, I wrote about Robert E. Howard. As I've researched these guys, I continually came up with a common name: Lord Dunsany, and I've been looking to write about him and his works.

It's fall, and I've been once again shifting from the usual topic of science fiction to horror and fantasy. Last year, I wrote about H.P. Lovecraft, and in my last column, I wrote about Robert E. Howard. As I've researched these guys, I continually came up with a common name: Lord Dunsany, and I've been looking to write about him and his works.