Annalee Newitz's Autonomous is a razor-sharp look at the future

/ In 2009, I got a phone call for what turned out to be an internship at a new website about science fiction and science fact called io9. At the other end of the line was Annalee Newitz, the site's editor, and we chatted about academics, science fiction, and what I wanted to write about. That was the start to a really wild ride, and ultimately has brought me to the place where I am today: writing about science fiction and science fact.

In 2009, I got a phone call for what turned out to be an internship at a new website about science fiction and science fact called io9. At the other end of the line was Annalee Newitz, the site's editor, and we chatted about academics, science fiction, and what I wanted to write about. That was the start to a really wild ride, and ultimately has brought me to the place where I am today: writing about science fiction and science fact.

So, I'll get it out of the way that I owe Annalee big time, but as with any book I crack open, I attempted to get into it objectively. Either way, I really adored Autonomous, her debut novel. It's a book that crackles with a really intriguing, nuanced vision the future of work, drugs, technology, and ownership that's both terrifying and exhilarating at the same time. If you want a review that's not mine, I wholeheartedly agree with my colleague Adi Robertson's take over on The Verge. (I did get to take the picture for the review!)

Set about a century in the future, Autonomous follows a pharma pirate named Jack who reverse-engineers drugs to give out to those in need. This future is ruled over by powerful governmental organizations that rigorously enforce property rights and ownership laws, where people and robots can be legally contracted out for work (really, a form of slavery), if they don't purchase an enfranchisement (citizenship) in any given territory.

When Jack reverse-engineers a drug called Zacuity, a work enhancement drug that gives its user a high while they go about their jobs. It turns out that it's highly addictive and leads to some bad outcomes: addicts become so addicted to their work that they don't do anything else, and they end up crashing trains or flooding cities, or just die from forgetting to take a break to drink water. Jack unleashes this drug on the open market, and has to turn around and figure out how to reverse-engineer a cure.

Meanwhile, this outbreak of addicts attracts the attention of the International Property Coalition, an organization that enforces intellectual property rights — with armed androids and soldiers. It sends a duo, Eliaz and Paladin, to track her down and take care of the problem.

Annalee plays with a lot of things in this book, and if you read io9 under her tenure, some of this will be familiar. The book plays out a sympathetic argument about intellectual property rights — how things like copyright and patents hamper innovation and contribute to the feedback loop that is capitalism. Jack and her academic compatriots are revolutionaries who work to try and break that system, opening free labs and pirating drugs.

On the other side of things, she explores some interesting thoughts on what the nature of work might be, for robots and humans. With the rise of intelligent robots, a system of contracts comes about: robots can offset the cost of their creation by going into a contract with their 'employers,' and people are brought in under the same system. It's essentially dressed-up slavery, and Annalee plays out these arguments between the Eliaz and Paladin's relationship.

The two dynamics tie into one another, but they are a bit uneven: this feels almost like two books smashed together, but they complement one another decently enough, essentially coming down to citizenship acting as another form of property.

As someone who wrote for io9, I really appreciate the sheer vibrancy of this book. It's packed with ideas and visuals and weird technologies. It's like walking through a crowded bazaar somewhere: there's too much to look and take in, and the book is a sensory overload in paper form. It's buzzing with huge ideas that warrant their own stories, but Annalee buzzes past them as the main narrative thunders along.

Ultimately, it's a fantastic, brilliant debut novel. I can't wait for her next one.

I finally finished slogging through Netflix's Iron Fist. I really enjoyed watching Daredevil, Jessica Jones, and Luke Cage, and I was interested to see how this one would turn out. It's... definitely at the bottom of the list when it comes to MCU entries.

I finally finished slogging through Netflix's Iron Fist. I really enjoyed watching Daredevil, Jessica Jones, and Luke Cage, and I was interested to see how this one would turn out. It's... definitely at the bottom of the list when it comes to MCU entries. This is a cool book I picked up recently: The Card Catalog: Books, Cards and Literary Treasures, written by the Library of Congress. It's a cool blend of history and visuals, and if you're nostalgic at all for the days of the card catalog or even libraries, it's well worth picking up.

This is a cool book I picked up recently: The Card Catalog: Books, Cards and Literary Treasures, written by the Library of Congress. It's a cool blend of history and visuals, and if you're nostalgic at all for the days of the card catalog or even libraries, it's well worth picking up.

I'm a sucker for durable space opera novels. I like crews on space ships flying around doing things in the vastness of space, and one of the books that I came across earlier this fall was Scott Warren's new novel Vick's Vultures.

I'm a sucker for durable space opera novels. I like crews on space ships flying around doing things in the vastness of space, and one of the books that I came across earlier this fall was Scott Warren's new novel Vick's Vultures. Nightshades was a book that I had placed on

Nightshades was a book that I had placed on  I have to admit, I hesitated a bit when my wife first showed me a picture of Tiki on her computer screen. We had just gotten married, and were in the final stages of getting a house. A dog was something that we had talked about for quite a while, and we had gone through the ups and downs of searching through countless pictures of pets from the local shelters. I had my heart set on finding a black lab, a type of dog that I've always seen as loyal and family-friendly.

I have to admit, I hesitated a bit when my wife first showed me a picture of Tiki on her computer screen. We had just gotten married, and were in the final stages of getting a house. A dog was something that we had talked about for quite a while, and we had gone through the ups and downs of searching through countless pictures of pets from the local shelters. I had my heart set on finding a black lab, a type of dog that I've always seen as loyal and family-friendly.

Earlier today, I got a new computer in the mail: an Acer Chromebook. For most of my freelancing / working life, I've used a work computer in my off hours to write up just about everything. When it became clear last year that I'd be leaving Norwich, I ended up buying a used iMac at a good price, which has been an absolute joy to use. It's reliable, user friendly, and didn't require too much effort to get used to.

Earlier today, I got a new computer in the mail: an Acer Chromebook. For most of my freelancing / working life, I've used a work computer in my off hours to write up just about everything. When it became clear last year that I'd be leaving Norwich, I ended up buying a used iMac at a good price, which has been an absolute joy to use. It's reliable, user friendly, and didn't require too much effort to get used to. I've always been more of a Marvel and Dark Horse Comics fan: I picked up a ton of Hellboy, Fantastic Four, Daredevil, Spider-Man and Iron Man comics over the years, but only the occasional DC comic: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen currently sit on my shelves. Superman, Green Arrow and most of the others really haven't interested me over the years, until I came across Darwyn Cooke's artwork.

I've always been more of a Marvel and Dark Horse Comics fan: I picked up a ton of Hellboy, Fantastic Four, Daredevil, Spider-Man and Iron Man comics over the years, but only the occasional DC comic: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen currently sit on my shelves. Superman, Green Arrow and most of the others really haven't interested me over the years, until I came across Darwyn Cooke's artwork. Like many people, I got hooked on Serial about halfway through the first season when I had heard a bunch of ads for it on NPR, and diligently listened to the rest of the season as Sarah Koenig, worked her way through the story.

Like many people, I got hooked on Serial about halfway through the first season when I had heard a bunch of ads for it on NPR, and diligently listened to the rest of the season as Sarah Koenig, worked her way through the story. Here's a book that I've been looking forward to for a long while, ever since it was first announced a couple of years ago: Charlie Jane Anders' All The Birds In The Sky. It's a stunning debut novel, one of the best that I've ever read.

Here's a book that I've been looking forward to for a long while, ever since it was first announced a couple of years ago: Charlie Jane Anders' All The Birds In The Sky. It's a stunning debut novel, one of the best that I've ever read. I'm trying to make it a point to read up on some of the books that I missed over the last couple of years. One, V.E. Schwab's A Darker Shade of Magic came recommended from all corners of the internet, and it lives up nicely to those reviews.

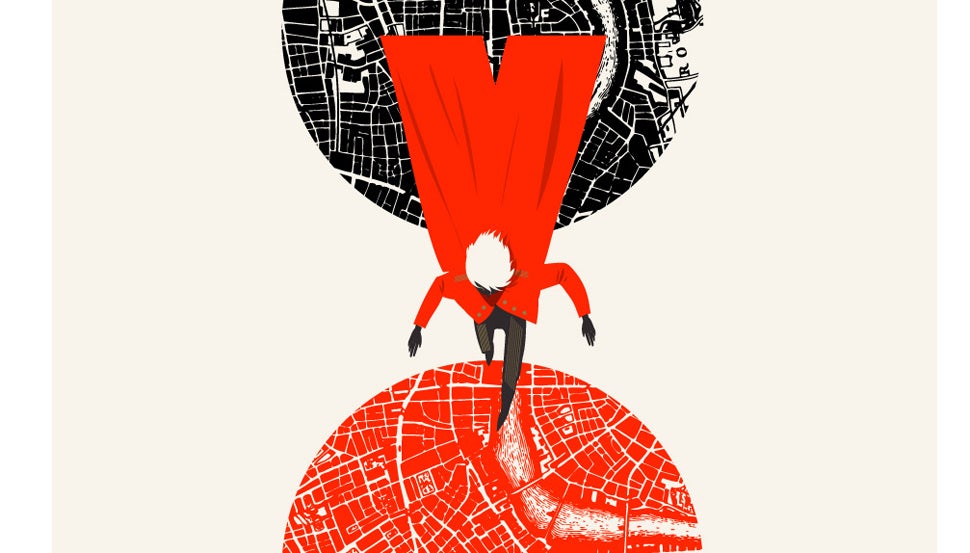

I'm trying to make it a point to read up on some of the books that I missed over the last couple of years. One, V.E. Schwab's A Darker Shade of Magic came recommended from all corners of the internet, and it lives up nicely to those reviews.

Ernie Cline's novel Armada dropped last week with an enormous publicity campaign that's sure to get this book selling exceptionally well. Cline has been riding high on his debut novel, Ready Player One, an Easter-egg infused novel that hit the nerd sweet spot with a hefty dose of references and nostalgia. The problem with Armada is that it's absolutely, fucking terrible.

Ernie Cline's novel Armada dropped last week with an enormous publicity campaign that's sure to get this book selling exceptionally well. Cline has been riding high on his debut novel, Ready Player One, an Easter-egg infused novel that hit the nerd sweet spot with a hefty dose of references and nostalgia. The problem with Armada is that it's absolutely, fucking terrible.

For me, the best types of history books are the one that look at something that seems innocuous, but turns out to be a small part in a much larger story. Mary Pilon's history The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World's Favorite Board Game is one such book, and it's an excellent look at the history of the board game Monopoly and how its history is murkier than one would ever expect. The board game you likely played as a family has a long, fascinating and exciting story behind it, and a story that ties into tax philosophy and business practices from major game maker Parker Brothers.

For me, the best types of history books are the one that look at something that seems innocuous, but turns out to be a small part in a much larger story. Mary Pilon's history The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World's Favorite Board Game is one such book, and it's an excellent look at the history of the board game Monopoly and how its history is murkier than one would ever expect. The board game you likely played as a family has a long, fascinating and exciting story behind it, and a story that ties into tax philosophy and business practices from major game maker Parker Brothers.