According to a random longevity calculator that I found on the web, my son, Bram (as a white male, born in Vermont) has a projected lifespan of 78 years, giving him until the year 2091 to live, provided everything remains the same. I'm guessing, given the age of some of my relatives, and the potential for progress in medical science, that there's a good chance that he could live to see 2100 and beyond. By the same measure, someone born in 1913 would live until 1991, or someone born in 1935 would live until 2013. It's an impressive range of time, and it gets me thinking about how things change from one time to another, and what it means.

It's a slightly morbid subject, but it's an interesting one to look at. I'm a historian, and recently, I've been reading quite a bit on the development of the 20th Century. Human nature generally gives us a short-term viewpoint for everything around us, and when it comes to imagining what the future holds for us, our art fails us. Science fiction doesn't really have a good track record, despite some notable predictions here and there from Verne and Clarke. SF is more about the present than it is about what the future will really be like.

So, what's Bram's world going to be like over the next eight decades? To get an idea of how things change, it's instructive to look at how much has changed since 1935 for some context.

Between 1935 and 1945, the Great Depression was underway and ending. World War 1 was just about two decades behind everyone, with those veterans now parents and trying to find work. The repercussions from the Great War no longer in the immediate forefront in US policy. Facism was on the rise in the world with Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler in power and actively breaking treaties. The Dust Bowl, a major ecological catastrophe, caused by over farming, loomed in the American Southwest. The WPA was formed by the Roosevelt administration, as well as the Social Security administration. World War 2 rose and broke over a majority of that time, with devastating, transformative consequences for the world. In the science fiction world, the pulps were started up and took off into a run, with the Golden Age starting up.

From 1945 to 1955: The Second World War ended with Hitler's suicide and the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan. The nuclear race started, with a Soviet bomb in 1949. The Korean war started and ended, and the Cold War began. The US was quickly becoming an economic powerhouse in the new world. Golden age of SF was still going strong. Novels were starting to appear, magazines were waning. The Baby boomer generation were around, and getting older.

From 1955 to 1965: Sputnik orbited the planet in 1957, and the first man went into space a couple of years later. The Cold War was still going strong, and the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs showed us that we could go into space. The Vietnam War was starting to brew (US not fully involved yet). John F. Kennedy was killed.

1965-1975: Vietnam War was going strong. Robert Kennedy was killed, as well as Martin Luther King. Counterculture was in full swing, and the Vietnam War reaches its peak and ended. We landed on the Moon, more than once, and launched Skylab in 1973. Computers were starting to appear in colleges.

1975-1985: Iranian revolution happened and began to change some things in the Middle East, while the 1st Persian Gulf War began. Space Shuttle program was in full swing. The Regan administration was elected. Science Fiction shifts from books to movies. Star Wars, Alien, Blade Runner were all released during this time. I was born.

1985-1995: 1st Gulf War, Space Shuttle Challenger, fall of the Soviet Union all happen. Computers begin to enter classrooms, introducing the Internet to students (like myself). We get a computer in our house for the first time. Babylon 5 starts airing.

1995-2005: The internet is here to stay. Terror attacks in New York City and Washington DC shift the political focus in the country. Soviet Communism is a pretty distant memory, with the threat of radicalized islamic groups taking their place. Star Wars is re-released and a new trilogy hits theaters. Firefly is aired and cancelled. Space Shuttle program suffers blow with Columbia's loss. The ISS begins construction in '98.

2005-2013: Social Media sites take over the web, internet communications are intensely monitored. I watch/read (almost) live as a Mars lander hits the surface of the planet. Space X becomes first private company to launch and dock with the ISS. The Space Shuttle program ends. Bram is born into a house that has eight computers (5 of them hand-held) and parents who are both working in a technology-based workplace.

There's a lot of changes in that time.

Born in 2013, Bram will never know a world in which the United States hasn't had an African-American president, where the mobile phone is one of the dominant and most proliferated pieces of technology on the planet, and where he can watch an astronaut fix a space station from his home. He can talk to someone on a video phone with the tap of a couple of buttons. He's growing up in a household with a robot in it.

He's never going to know a world where there's more hours of Star Wars: Clone Wars episodes than there are of the Original Trilogy. He'll never know a household where there isn't something to do with that franchise kicking around. He'll never know a world in which the space shuttle was in operation, but he will know one where private operations are in existence, even flourishing. In all likelihood, he'll see people land on the moon again, as well as seeing manned missions to asteroids, Mars and potentially, the moons of Saturn and Jupiter. He'll see the beginning of a new space program, Orion. He's growing up in a world where he'll never know a World War I veteran.

Politically, while he's growing up in a state that's one of the least diverse in the US, he's part of a generation that's going to be amongst the most diverse in the country - ethnically, sexually, politically. This'll have major implications for policy and the general makeup and attitude of Americans. He's the beneficiary of a world that doesn't have Osama Bin Laden or Saddam Hussein, but there's plenty of other bad people in the world to take their places. He'll see the final years of the war in Afghanistan.

Environmentally, he's going to get the full brunt of global anthropomorphic climate change. If he stays in Vermont, we'll likely still see extreme winters, but as global temperatures rise, the state will most likely see a collapse of its Maple Tree population as it gets too warm for them - no more glorious fall hillsides. Invasive species will decimate other tree species, which makes me wonder if we'll see more evergreens over maples and ashes. Vermont will have its own issues as we see major storms pass over the state - our geography will lend itself to major flooding throughout the fall and spring seasons, and parts of the state will need to be reinforced against it, with more green spaces in flood plains, or total abandonment of some areas.

Computer-wise, he's never going to know a time without a computer. A mobile phone that was pure imagination in 1935 took his first picture minutes after he was born, and he sees us work and watch things on our home computers. He's entering an age when the television isn't supreme: we don't have live TV in the house at all. Moore's Law will probably end, but computers will grow increasingly faster. Almost half of the world's population will have access to the internet.

Bram will be 10 in 2023. Countries such as China, India and Brazil will likely be major world powers alongside the US, and we'll likely see major space efforts to reach the Moon and Mars during this time. Bram's schooling will probably have a lot to do with computers and online classrooms. We'll probably see autonomous cars and aircraft more often, but not everywhere. The ISS will be decommissioned and will be deorbited over the Pacific Ocean. The veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars will be in their 30s/40s/50s, and the conflicts will start to pass into history. They'll likely become precursors to other major conflicts in the region as it continues to stabilize after the Arab Spring a decade earlier. The US will be composed of a far different ethnic makeup, and there'll likely be some grumbling about that. I'm guessing that women will become a more dominant part of the workplace, while transgendered and non-CIS folks will be far more accepted than they are now. The 99942 Apophis will pass by us, but won't impact. I'll be 38.

Bram will be 20 in 2032. The world population will be at least 8 billion people. io9 predicts that we'll have some form of AI, computers everywhere, major effects from climate change (and mitigation projects), 3D printed organs, and more space travel and settlement. Bram will probably be in college or about to leave. His job likely doesn't and can't exist right now. 99942 Apophis could impact the planet. I'll be 48. The last remaining World War II veterans will have died.

Bram will be 30 in 2043. Bram will have some form of job that's unheard of now. Global climate change will bring up major storms, and will likely be the cause of conflicts as the global population shifts around. Africa will see some major growth, if not before. I'll be 58, and maybe, I'll be a grandfather.

Bram will be 40 in 2053. The world's population will be at least 9 billion people, putting a huge strain on resources, provided that economics and infrastructure are insufficient. We might very well see the construction of a space elevator. I'll be 68 - Maybe I'll be retired, if such a thing still exists.

Bram will be 50 in 2063. Lunar mining operations might be around, and a good chunk of our energy will come from renewable energy. I'll be 78, my projected life-span, if nothing else changes. Megan will probably outlive me.

Bram will be 60 in 2073. Space and international travel might be pretty easy to go do, but still expensive. I could be 88.

Bram will be 70 in 2083. China will likely be the major global power on the planet. We might be able to live on the Moon. I could be 98.

Bram will be 80 in 2093, the end of his projected lifespan - he might go far past that. The planet might be completely converted to renewable energy by this point. The world will be completely different from now, ecologically, politically, socially. The last veterans of the Iraq / Afghanistan wars will be few in number. I'll be 108. Who knows what science fiction will bring at that point?

The point to all of this isn't to be predictive: it's to think about how much things will have changed. It's easy to imagine our lives right now with things like space travel, 3D printed organs and computers controlling everything, but the ramifications on how that affects everything is much harder to predict. Very few people in the 1800s had any idea of what the world a century later would look like, and the same is exactly the same now. It's a nebulous point in time, but there's one major point to keep in mind: things will change, and we can't - and shouldn't - expect to build a world that's a mirror of our own. My world isn't and never will be Bram's - he'll have is own.

One of the major takeaways from this is that he's likely going to lead a very different life from the one I've lived, something that's relatively new in human history: up through the industrial revolution and even deep into the 20th Century, families often followed similar paths: sons would take their occupation from that of their father, and so forth. The shift is even more jarring when it comes to female employment. My father works in business and geology; I work as a freelance writer and educational administrator for a job that simply didn't exist when I was born, or largely in the last two decades (online education is still a young field). Bram will probably do something completely different, and in a field that simply doesn't exist yet. More than just employment, though; the lessons, habits and personality that he picks up from Megan and myself will come with him, and it's something that remains at the back of my mind. Hopefully, we'll impart habits of generosity, friendliness and curiosity to him, and hopefully, those will be traits that will aid him throughout his life.

If things go well, Bram might be among the first generations of people who could easily leave the planet and go somewhere else. He'll be the recipient of technologies that will fundamentally change how humans live and interact with one another, and will continue to accelerate our development moving forward. Interestingly, while we can make some scientific predictions (I'd bet that most of them will come faster than we expect), I can't get a good idea of most of the geopolitical ones.

These are all guesses. Looking at science fiction, it's clear that their guesses for the future were sometimes correct, but more often wildly off target. There's things that we know, barring something major and unforeseen: global climate change will be a factor in life. The prevalence of technology will continue. People will act like jerks to one another, and there'll be a lot more of us.

I hope that we'll see some of those things come to fruition, and that we'll be fortunate enough to live to see them. Those predictions? Science fiction, especially as you get further and further away. Looking back at the past, they'll likely marvel at just how much they've changed in their own generation.

In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history.

In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history.

This coming week is the

This coming week is the  One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him.

One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him. The latest issue of

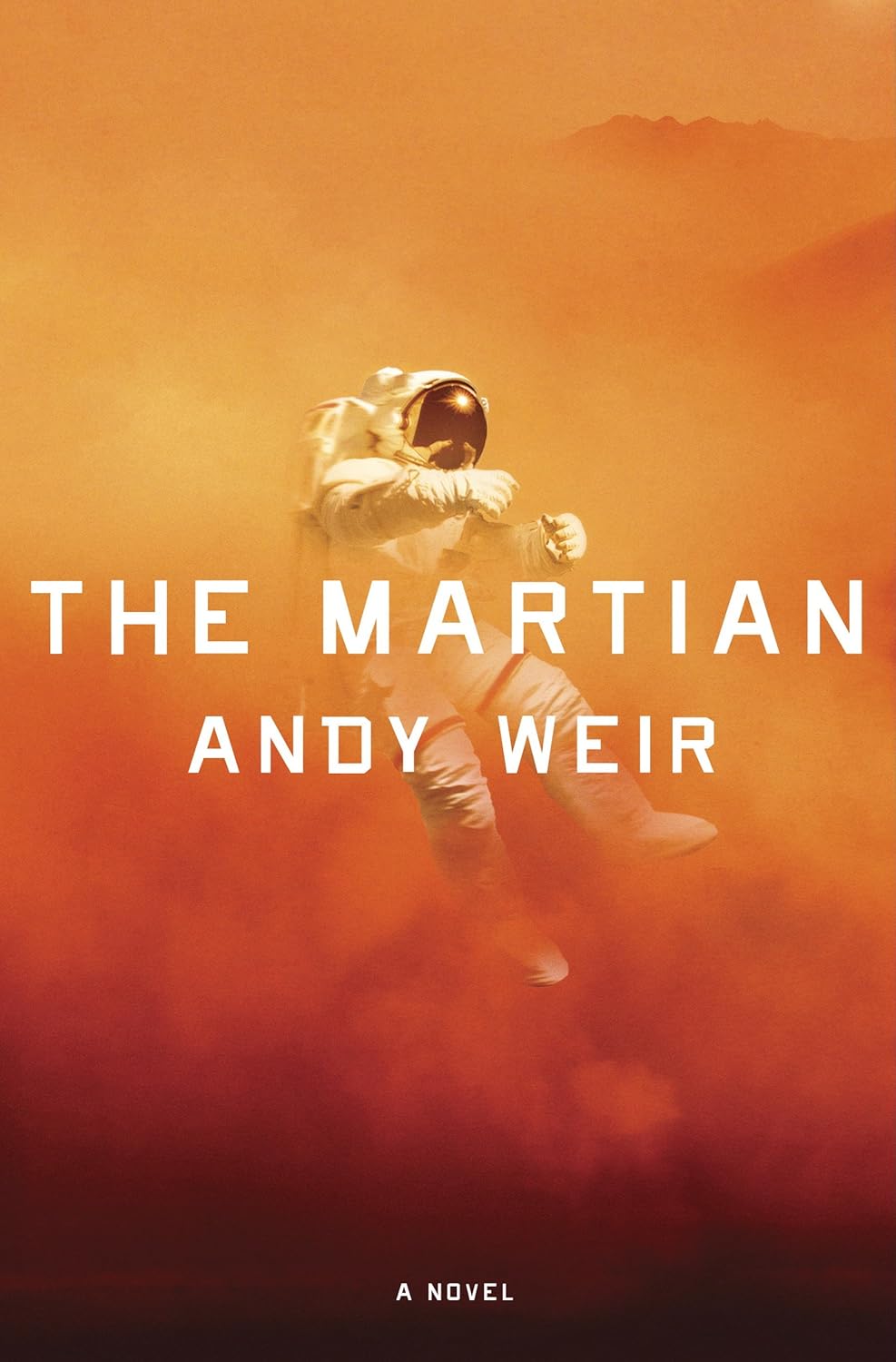

The latest issue of  Andy Weir's first novel, The Martian: A Novel, has garnered a lot of buzz lately: it's an addicting, rapid-fire book that runs along with a manic energy that makes it difficult to put down. You know how you slow down while passing an accident on the high way? I had that reaction as I blew through it, waiting to see just how Astronaut Mark Watney would survive.

Andy Weir's first novel, The Martian: A Novel, has garnered a lot of buzz lately: it's an addicting, rapid-fire book that runs along with a manic energy that makes it difficult to put down. You know how you slow down while passing an accident on the high way? I had that reaction as I blew through it, waiting to see just how Astronaut Mark Watney would survive. My Facebook wall blew up this morning with the following news: Star Wars author Aaron Allston collapsed at a

My Facebook wall blew up this morning with the following news: Star Wars author Aaron Allston collapsed at a

When Megan and I started dating, I made the trip from Vermont to Pennsylvania. It's around eight hours, covering four states. On one such trip, I decided I really didn't want to endure New Jersey, and took an early exit off of I-87 toward the alluring sign 'Delaware Water Gap'. It didn't take me much longer to cut through the two-lane road, perfect for driving a Mini Cooper on, and it took me through a quiet, quaint looking town of Milford. Since Megan and I have married, we make the trip frequently, crossing through Milford a couple of times a year. I like the town, even though I've never stopped.

When Megan and I started dating, I made the trip from Vermont to Pennsylvania. It's around eight hours, covering four states. On one such trip, I decided I really didn't want to endure New Jersey, and took an early exit off of I-87 toward the alluring sign 'Delaware Water Gap'. It didn't take me much longer to cut through the two-lane road, perfect for driving a Mini Cooper on, and it took me through a quiet, quaint looking town of Milford. Since Megan and I have married, we make the trip frequently, crossing through Milford a couple of times a year. I like the town, even though I've never stopped. The first Blish story I read was Surface Tension in Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology. While there's certainly some issues with the anthology, it's a solid collection of short fiction. Blish isn't an author I've read extensively, but I remember him popping up frequently in the various anthologies I read over the years.

The first Blish story I read was Surface Tension in Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology. While there's certainly some issues with the anthology, it's a solid collection of short fiction. Blish isn't an author I've read extensively, but I remember him popping up frequently in the various anthologies I read over the years. There were two authors I read extensively when I first started reading science fiction. The first was Isaac Asimov, because, well. Robots. Foundation. Reasons. The other was Arthur C. Clarke. The first story I really remember reading from him came from a thick anthology cultivated by Asimov, with one fantastic story by Clarke in it: Who's There? I then ran through a bunch of his books: 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010, 2061 and 3001 are the ones I checked out over and over again. Later, I dug into Rama and even later, Childhood's End.

There were two authors I read extensively when I first started reading science fiction. The first was Isaac Asimov, because, well. Robots. Foundation. Reasons. The other was Arthur C. Clarke. The first story I really remember reading from him came from a thick anthology cultivated by Asimov, with one fantastic story by Clarke in it: Who's There? I then ran through a bunch of his books: 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010, 2061 and 3001 are the ones I checked out over and over again. Later, I dug into Rama and even later, Childhood's End.

The nominations period for the Hugo Awards are now open! This year's World Science Fiction convention will be held in London. Nominations are open through March 31st.

The nominations period for the Hugo Awards are now open! This year's World Science Fiction convention will be held in London. Nominations are open through March 31st.

2013 was a rush. So many things happened that have never happened to me before, all positive.

2013 was a rush. So many things happened that have never happened to me before, all positive.

Over the course of writing this column for Kirkus Reviews, I've found that the early women authors writing in the genre were some of the most influential, producing some incredible stories over their careers. I've looked at quite a few who were incredibly influential:

Over the course of writing this column for Kirkus Reviews, I've found that the early women authors writing in the genre were some of the most influential, producing some incredible stories over their careers. I've looked at quite a few who were incredibly influential:

I never read the Tom Swift novels as a kid; I was always more obsessed with the Hardy Boys series. Over the years, I've read bits and pieces about Edward Stratemeyer, the man who was behind the long-running book series, as well as those of Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins (a favorite of my mother's), The Rover Boys and Tom Swift. He conceived of a character, put together a formula, and had a freelancer ghost write the novel before editing it. The process has always fascinated me, but when it came to looking into his background, an entire segment of early science fiction comes to light: the Dime Store novels, which created entire subgenres in their own right. More than that, they carried with them some real kernels of thematic material which have since propagated far into the future, which surprised and delighted me.

I never read the Tom Swift novels as a kid; I was always more obsessed with the Hardy Boys series. Over the years, I've read bits and pieces about Edward Stratemeyer, the man who was behind the long-running book series, as well as those of Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins (a favorite of my mother's), The Rover Boys and Tom Swift. He conceived of a character, put together a formula, and had a freelancer ghost write the novel before editing it. The process has always fascinated me, but when it came to looking into his background, an entire segment of early science fiction comes to light: the Dime Store novels, which created entire subgenres in their own right. More than that, they carried with them some real kernels of thematic material which have since propagated far into the future, which surprised and delighted me. Last night, War Stories officially tipped over the 100% mark and officially funded. As of this morning, we've reached 104% of our goal, and with 33 hours left to go, we're hoping to hit a couple of additional goals above and beyond that.

Last night, War Stories officially tipped over the 100% mark and officially funded. As of this morning, we've reached 104% of our goal, and with 33 hours left to go, we're hoping to hit a couple of additional goals above and beyond that.