Transcriptions

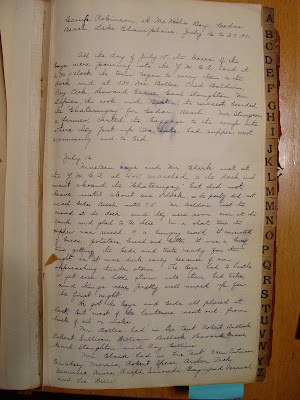

/ Back in December, I received a digital copy of Byron Clark's journal - a goldmine of information on my subject - dates, thoughts, and details that I didn't really have a good grasp on before.

There are 659 high quality images that makes up the entire journal, with a number of images, hand-written notes and news paper articles.

Currently, I'm transcribing the entire thing. I'm finding that it's the best way for me to understand the sequence of events that occurred at camp, and what Clark was thinking. So far, I've transcribed about nineteen pages of handwritten text, from the beginning of the first camping session to just after.

It's absolutely astounding to what information is in those pages, about that first camping session, about the foundation upon which a lot of my life has essentially been based on. There's a bunch of things that I knew about, but mostly just general things. Here was specific, day by day information about the first camping session, with some things that really stood out. For example, I was unaware that the frist campers started a secret society, and that five of the campers were kicked out towards the end for stealing 30 bananas.

I think that I'd be able to finish my paper without this, but it would be severely diminished. Fortunately, I was able to obtain a digital copy of this, which brings me to my next point - digital copies of physical documents is going to be an essential tool for researchers as technology and access developes further. Currently, the main problem with this is the sheer volume of materials that do not exist as a digital copy. Currently, according to an article in Seven Days, there's efforts underway for high resolution scans for some of the state's older documents, like the State Constitution. A couple months ago, I tried looking into getting mission reports for various Infantry and Armored divisions for D-Day to work on my Normandy paper a bit more, to no avail - according to the man I spoke with, there are just too many mission reports and files in hard copy, that the process will take years, if not decades of dedicated work. Another person I spoke with about military files stated that an entire repository was destroyed by fire a couple years ago - raw information that is lost forever.

The advantages of digital scanning and replication are clear - it allows, first and foremost, a backup copy, something that really hasn't been available to historians before. Originals of documents, barring extraordinary cases, don't last the long, and are susceptible to changes in heat, temperature, humidity and human interactions. A digital copy would practically eliminate that, provided that a secure digital filing system can be perfected. (From what I have read and understand, there's no sure way to store digital information, something that, interestingly, the film industry is currently up against when storing film data files.) Additionally, digital copies make distribution of documents and files much, much easier, either via online databases such as JStor or similar sites, or on a user to user basis. There's an entire industry here, as these sites aren't free, and are generally used by universities and institutions.

The main downside is probably going to be an ongoing argument regarding the nature of information and its distribution via the internet. Should information be completely free? And if historical documents are brought to the digital world, who will control it? The company or institution that does the scanning and storing?

I can see this opening up some problems for researchers. What is to prevent institutions from selectively releasing information to researchers to alter histories? While the government has laws that allow for transparency (which should help military historians), I'm not aware of any such laws that could operate with the private sector.

That being said, digital copies would also make historian's lives easier, because it really doesn't help when you need physical copies, and they're 7-10 hours away by car.

Back in December, I received a digital copy of Byron Clark's journal - a goldmine of information on my subject - dates, thoughts, and details that I didn't really have a good grasp on before.

There are 659 high quality images that makes up the entire journal, with a number of images, hand-written notes and news paper articles.

Currently, I'm transcribing the entire thing. I'm finding that it's the best way for me to understand the sequence of events that occurred at camp, and what Clark was thinking. So far, I've transcribed about nineteen pages of handwritten text, from the beginning of the first camping session to just after.

It's absolutely astounding to what information is in those pages, about that first camping session, about the foundation upon which a lot of my life has essentially been based on. There's a bunch of things that I knew about, but mostly just general things. Here was specific, day by day information about the first camping session, with some things that really stood out. For example, I was unaware that the frist campers started a secret society, and that five of the campers were kicked out towards the end for stealing 30 bananas.

I think that I'd be able to finish my paper without this, but it would be severely diminished. Fortunately, I was able to obtain a digital copy of this, which brings me to my next point - digital copies of physical documents is going to be an essential tool for researchers as technology and access developes further. Currently, the main problem with this is the sheer volume of materials that do not exist as a digital copy. Currently, according to an article in Seven Days, there's efforts underway for high resolution scans for some of the state's older documents, like the State Constitution. A couple months ago, I tried looking into getting mission reports for various Infantry and Armored divisions for D-Day to work on my Normandy paper a bit more, to no avail - according to the man I spoke with, there are just too many mission reports and files in hard copy, that the process will take years, if not decades of dedicated work. Another person I spoke with about military files stated that an entire repository was destroyed by fire a couple years ago - raw information that is lost forever.

The advantages of digital scanning and replication are clear - it allows, first and foremost, a backup copy, something that really hasn't been available to historians before. Originals of documents, barring extraordinary cases, don't last the long, and are susceptible to changes in heat, temperature, humidity and human interactions. A digital copy would practically eliminate that, provided that a secure digital filing system can be perfected. (From what I have read and understand, there's no sure way to store digital information, something that, interestingly, the film industry is currently up against when storing film data files.) Additionally, digital copies make distribution of documents and files much, much easier, either via online databases such as JStor or similar sites, or on a user to user basis. There's an entire industry here, as these sites aren't free, and are generally used by universities and institutions.

The main downside is probably going to be an ongoing argument regarding the nature of information and its distribution via the internet. Should information be completely free? And if historical documents are brought to the digital world, who will control it? The company or institution that does the scanning and storing?

I can see this opening up some problems for researchers. What is to prevent institutions from selectively releasing information to researchers to alter histories? While the government has laws that allow for transparency (which should help military historians), I'm not aware of any such laws that could operate with the private sector.

That being said, digital copies would also make historian's lives easier, because it really doesn't help when you need physical copies, and they're 7-10 hours away by car.