The Real Robotic Revolution: P.W. Singer and August Cole's Burn-In

/In 1920, Czech playwright Karel Čapek published an unusual work: a play called Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, or Rossum's Universal Robots. Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction cites the play as the first use of the word “robot,” and ever since, robots have been a fixture of science fiction drama, used by countless authors throughout science fiction’s long history, who have imagined all of the ways that they could break, help, murder, or otherwise exist alongside humanity.

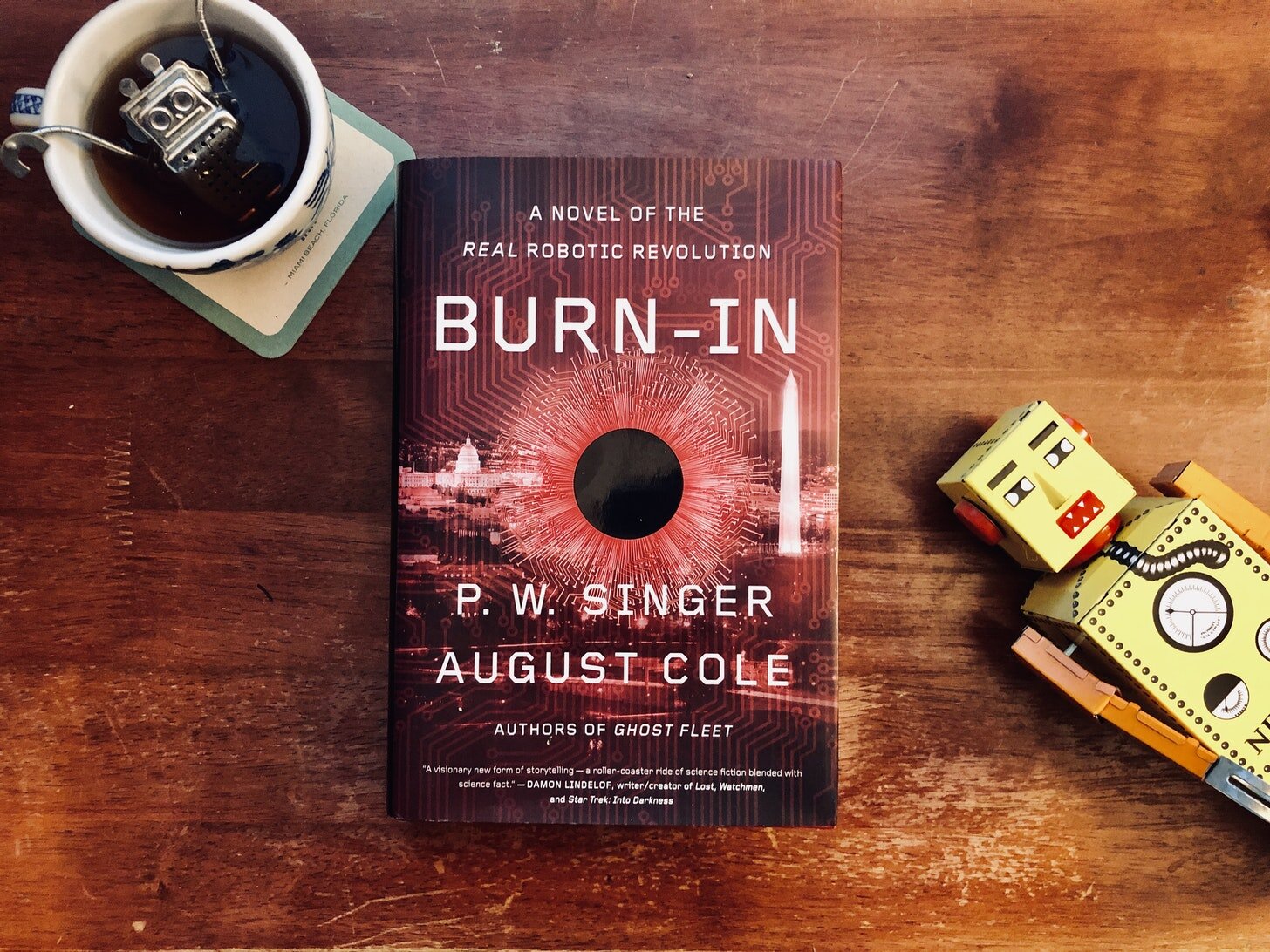

One of the latest books to look at the world of robotics is Burn-In: A Novel of the Real Robotic Revolution by P.W. Singer and August Cole. The two collaborated on 2015’s Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War, a near-future thriller that blended the then-present-day advances in military hardware with geopolitical friction between the United States, Russia, and China. The result is a book that’s eerily been coming true, piece by piece. Now, the pair replicate their approach to look at what the near future might hold for robotics.

Set in the 2030s, the pair depict a future that feels like it could come true tomorrow. FBI Special Agent Lara Keegan goes about her work trying to capture a suspect amidst a wide-scale Veteran protest and series of domestic terror attacks, aided by facial recognition that’s beamed into her glasses, self-driving cars, origami drones, and more. She’s soon tasked with a new partner: a police robot called TAMS (Tactical Autonomous Mobility System). Her job is to give it a shakedown — a burn-in field test to see if it’ll be useful to officers in the field, and to help it better understand human interactions. TAMS proves to be a useful partner as she and her fellow agents work to track down an extremist bent on a major attack in Washington DC.

TAMS is certainly the highlight of the book — it’s simultaneously inhuman, but is fleshed out nicely: you can’t help but imagine that it’s sentient. It’s something I (and soldiers who have worked closely with robots on the battlefield) can relate to a bit: I’m very attached to my home’s Roomba, Rosie (and “her” newer sibling, Robbie.) The same is true with TAMS.

This is the key to the success of Cole and Singer’s brand of science fiction (the aforementioned FicInt, of which this is an example): it has a foot firmly planted in reality, while stepping forward in time a bit by extrapolating forward from 2020. This worked for Ghost Fleet, in which we see a range of then-theoretical or novel military technologies like drone swarms, automated ships / vehicles, hijacked tech because of poor supply-chain security, and so forth. While Cole and Singer still have their eyes on the future of the military, the building blocks that they’re playing with here show how porous the barrier between military and civilian technologies. Their characters stock up on food with apps and algorithms, appear in bystander videos that go viral, and contend with hacks and cyberattacks against insecure public infrastructure.

If some of those items sound familiar, it’s because they’re all things that have taken place. Novels usually carry a disclaimer in the front that says that the story and characters are fictional. In this novel, it reads: “The following is a work of fiction. However, all the place, trends, technologies, and incidents in it are drawn from the real world.” The end of the book has a thick section of footnotes of links to technology news from the last couple of years, everything from data security to robotics.

But what makes Burn-In a bit more of an effective read is that Cole and Singer don’t just focus on the technological gains that we can expect in the coming decade: they look at the effects of automation. What happens when you have a huge number of white men thrown out of work because their jobs have been automated out of existence? Keegan’s ex-husband is a good example here: he’s getting by as a gig worker helping elderly clients navigate their lives virtually, and is getting more radicalized by politicians and internet commentary that’s designed to steer people towards a more right-wing worldview (in this case, it’s also presented as very anti-technology).

This is an idea that’s central to robotic stories, because it’s fundamentally about how they change how we live. Cole and Singer aren’t arguing that robotics are bad in Burn-In: we plainly see how useful these things can be. But they’re warning that robotic, computer, and autonomous systems as we’re currently designing them are fragile — as are the cultural, political, and social systems that we live with today.

Apps that summon autonomous delivery robots aren’t the problem: it’s that they’re implemented without thought for the larger context in which they fit into the world. Uber, for example, has decimated the traditional Taxi market. On-demand delivery services and platforms are having a terrible effect on local restaurants and eateries. In doing so, Cole and Singer demonstrate the value of this type of fiction: it helps identify potential breaking points by framing them in a dramatic way, and Burn-In serves a bit as a warning sign for how things could go. It’s a scary future that they present, and in all likelihood, much of it is going to become very, very real.