This past weekend was Boskone 49, a science fiction / fantasy literature convention down in South Boston. After great experiences at ReaderCon the past couple of years, I decided to head down and partake in the fun for the spring, hitting up a bunch of panels and getting to meet up with people that I've largely talked to online over the past couple of years.

This past weekend was Boskone 49, a science fiction / fantasy literature convention down in South Boston. After great experiences at ReaderCon the past couple of years, I decided to head down and partake in the fun for the spring, hitting up a bunch of panels and getting to meet up with people that I've largely talked to online over the past couple of years.

Stepping in the door (after a typical Boston driving experience) on Friday afternoon, I saw one of my former college professors, F. Brett Cox, and Lightspeed publisher John Joseph Adams, which was nice, before heading off to the first of several panels: Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror in the Classroom, led by Brett, where they talked at length about the recent acceptance of the genres in the academic field. Since Cyberpunk has become a subgenre, it's become relevant, but with the addition of several literary heavyweights, such as Michael Chabon and Margaret Atwood, it's become more acceptable.

Typically, short fiction seems to be one of the best ways to get the literary themes across, but novels and films are also well used. What everyone seemed to agree on was that students really took to the genre, regardless if they were fans: students seem to identify with it quite a bit more than other genres.

Someone on the panel had a great quote, one that applies to more than just learning, but also critical reviewing and thinking as well: "I get to look under the hood and see how this works."

The next panel was Occupy SF: Corporations in Science Fiction, which was a fascinating talk. Charles Stross opened with some interesting things to think about: what holds up value in an interstellar empire? Apparently, this is the topic of his next book, and it drove discussion a bit early on, with some discussions about the very nature of money and economics. In comparable situations, letters of credit have been used on Earth, but how does this work when distances across space can be hundreds, if not thousands of years? Stross also suggested that if we're going to use metals for currency, we should simply use plutonium: it literally burns a hole in our pockets, and if we have too much, we can simply blow it up.

Finally getting to the point of corporations, they were likened to that of a hive: individuals carry out instructions on the behalf of the corporate hive, for its own (and presumably theirs), betterment. This is fine, in theory, but when you have an unchecked capitalist model, it will simply consume itself, because people aren't good at looking and planning in the extreme long-term: corporations simply work to make money and continue their operations (good and bad).

Leadership followed this discussion, and the point to which we've gotten represents a major change in how corporations were led: a very good point was brought up about who leads these places and what governs them: corporate behavior rewards psychopaths, and interestingly, a set of objective rules are set up to govern success: the value of experience has been lessened, because the rise of the MBA degree essentially has made corporate leadership interchangeable. Top earners are promoted and valued, regardless of how they become those top earners. As someone in the audience commented, that undermines what the customers think of the corporation. Long-term, that matters, but not so much in the short term.

This was an enlightening talk, and it was one of a couple that were very, very thought provoking for me personally, and gave me some great, solid ideas for a couple of projects that I've got in the works.

Saturday morning, I started with SF As a Mirror on Society, which I came in for about half of. Fortunately, this time, I left my car in Cambridge and rode in on the T, which reminded me that I dearly miss public transportation. I wish that I could ride a bus, subway or train to work. As I entered, I came in on a discussion of the 'Other', and some discussion on how some of the neglected characters should be handled: essentially, not embellished.

Following that, it was off to lunch, with Theodore Quester and John Joseph Adams, the Lightspeed crew present at the convention. Good times.

Lunch went a bit long, and when I got back, I got into a panel a bit late: Robocop Futures. This was a fascinating panel. As I got in, there was some discussion on the the role of people in systems: increasingly, we're living in a world that's guided by policy, rather than human intervention. I was reminded of something that P.W. Singer talked about when talking about robotic systems: people in the loop. People are increasingly out of the loop, where they're able to defer responsibility.

This is connected to law policies: increasingly, there are mandatory sentences and policies. One of the panelists mentioned a case where a Briton was prevented from entering the US because of a tweet. In this instance, everybody involved knew that it wasn't a serious or credible threat: policy demanded that the airport report it to law enforcement, who was in turn forced to investigate it, despite knowing that it wasn't a serious or credible threat. In the same manner, mandatory minimums for certain crimes: people aren't able to use their judgment in the process.

This discussion ended up on automated systems, which parse our conversations online. Increasingly, we've found ourselves turning to automated systems that absolve us of responsibility. Fortunately, computers are pretty bad at making sense of human relations. At the same time, people in the system are the weaker links that can potentially be exploited.

After a short break, Table Top Games in the Digital Age was the next one, with Ethan Gilsdorf moderating. This one was really one of the bigger letdowns: I'd been hoping that there would be some discussion about how table-top gaming might make the jump into the digital age, but there was a lot of lamenting about how the day of face to face gaming seemed to be going by the wayside (from the audience as well). It felt very oppositional to me, rather than a group looking at what was both inevitable coming, but also how to work the social aspects into the gaming world. This was covered, but briefly.

The next panel was fascinating: War of the Worlds and Dracula, compared. Both novels are ones that I read a long time ago, back in college, and I've been meaning to revisit them at some point. Discussion started right off with a look at both novels as reactions to Britain's place in the world: essentially, they're both reverse colonization novels, with two different models that tapped into an undercurrent of fear from British society:

- Invade, and replace the inhabitants with your own people.

- Invade, and change the inhabitants into your own people.

As someone noted early on, the Martians did to the British what the British did to the Zulu: invade, use overwhelming force and wreck havoc. In addition to these two novels, there was an entire subgenre of invasion novels from around the 1870s, right around the same time that Germany had begun to gain power in Europe. Britain's place in the world had begun to fall, and that's expressed in these novels: it's not too unlike the Cold War between the USSR and US. Both novels feature bloodsuckers feeding on Englishmen.

Something that I realized shortly after that both novels relied on the inherent strengths within the British lifestyle and culture: The British prevailed because their very biology helped them in War of the Worlds, while Dracula was hunted down with modern technology, which again taps into the patriotic element of both books. It was a fantastic panel, one that I learned a lot from.

The panel on Cover Art was an interesting talk, and the last for the night, with representatives from Tor Books and Baen. Baen's was interesting, where they have a particular style to their covers, but it was interesting to see their rational behind the art. Tor had some great cover examples, and overall, it was fascinating to see everything that goes into the covers of a book, and how it's used as a marketing tool.

On Sunday, Joshua Bilmes (Agent), David G. Hartwell (Editor), Patrick Nielsen Hayden (Editor), John Scalzi (Writer) and Toni Weisskopfgot (Editor / Publisher) together for their Top Ten Tips for the Prospective Writer, which was a interesting talk for anyone who is looking to become a professional author. There were actually more than ten tips, but they were all good ones. In short form:

- Be a good writer.

- Get used to sucking. You're at the beginning of a journey through incompetence. Keep writing until you don't suck.

- Divest yourself of attachment to writing times/locations: set aside a time, and write where ever. You'll have a new excuse everywhere you go to not write.

- A writer can do anything, provide its not what he's supposed to be doing.

- Write every day. Now is a good time to write.

- Two things: you can be a writer, then you can be a published author.

- Treat it like a job: be professional about it, and commit to it.

- Write to entertain someone else, not you.

- Know your audience.

- Who's going to be your first audience? Your editor and publisher.

- Give yourself space with no other intention other than to learn. Write so that you know how to put together a story.

- Publishers want to see a manuscript that you care about: they don't want to see your nanowrimo novel.

- Acknowledgments are a good roadmap.

- Understanding the industry are extraordinarily important. You have a better chance sending things to the right people. However, it is a moving target: trends change quickly. Urban fantasy was big four years ago. Much smaller now. If something's hot, it's too late.

- Write the book that you'd like to read.

- Half of your money that you earn goes to taxes.

- There will be people who are better than you and some who are worse. Publishing isn't fair.

- Publishers will put money where they think they'll get a return.

- Workshops are good, but make sure that you apply the advice that you get. Do some work shopping and then stop. The same workshop will ultimately give you the same advice over and over again.

- Your submission manuscript that's accepted is your final one: you're in the pipeline, not your writing workshop. Don't make drastic changes.

- Wheaton's law: don't be a dick.

- Scifi has an unusual amount of flow between pro and fan. Be nice to others.

- Esteem of your peers: nice to have it, but it's not essential.

- Don't be distracted by non-paying things that don't help you.

- If you enjoy it, you should do it. Don't do it if you don't like it.

- Write the best that you can, understand that everyone else is writing the best that you can, and don't crap on people. Admire the good works of others.

- Learn how to apologize and learn how to do it sincerely.

Good primer of advice there from some people who know that it works.

I got to wander around a little, before ending up at John Scalzi's reading, where he read from his upcoming novel Red Shirts and his non-fiction book, 24 Frames into the Future.

Redshirts sounds hilarious, and I'm glad that I've been watching Star Trek, because it's got a lot of inspiration from that particular franchise. It'll be interesting to see what Trek fans think once it's published. John's got a very fun style when it comes to panels, and this one was rapt with attention and a healthy dose of dry wit. Unfortunately, he wasn't able to stick around, due to a death in the family. I didn't get my copy of Fuzzy Nation signed, but that's okay: I got my copy of Rule 34 signed by Charles Stross, and The Warded Man by Peter Brett (which I'm going to read soon!), which was very cool.

With that, it was a good convention: I'm not sure I had as much fun as Readercon, but it was a good time, where I got to meet up with some very cool people: Myke Cole, F. Brett Cox, Peter Brett, John Scalzi, Charles Stross, Ian Tregillis (who's book Bitter Seeds is now on my to-read list), John Joseph Adams, Genevieve Valentine, Theodora Goss, Irene Gallo, and a whole bunch of others that I'm forgetting. Already, I can't wait to go back next year.

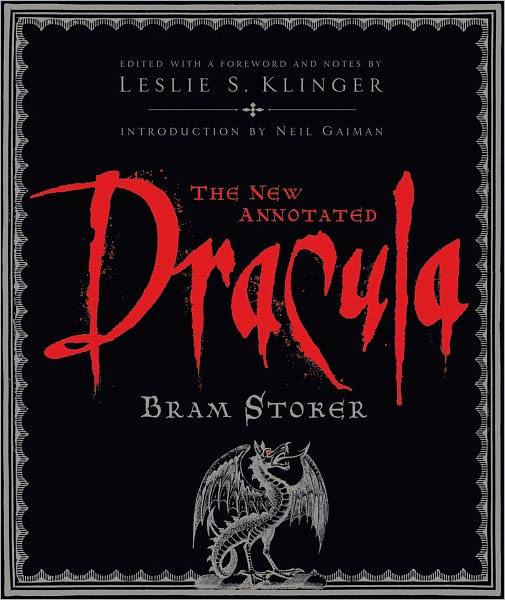

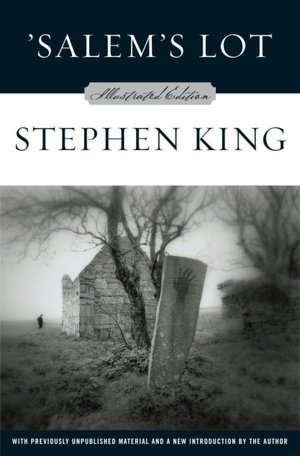

I had a gap in the schedule, and it seemed like a good time to start getting ready for October. Somewhere, I decided that I wanted to take a look at a broad swath of a genre, and because I was working on the pieces for October (Dracula), it seemed as good a time as any to see where Dracula fits into the larger picture. Turning to social media, I asked people what they thought were some of the more important vampire novels, coming up with an impressive list that had to be really pared down. There's not a lot of surprises on it, but I did find a couple of interesting points: many people believe that Dracula was *the* original Vampire novel, when in fact it's predated by a number of others that in turn influenced Dracula. Stoker's novel proves to be a tipping point, and there's quite a bit of variety after the publication of that book.

I had a gap in the schedule, and it seemed like a good time to start getting ready for October. Somewhere, I decided that I wanted to take a look at a broad swath of a genre, and because I was working on the pieces for October (Dracula), it seemed as good a time as any to see where Dracula fits into the larger picture. Turning to social media, I asked people what they thought were some of the more important vampire novels, coming up with an impressive list that had to be really pared down. There's not a lot of surprises on it, but I did find a couple of interesting points: many people believe that Dracula was *the* original Vampire novel, when in fact it's predated by a number of others that in turn influenced Dracula. Stoker's novel proves to be a tipping point, and there's quite a bit of variety after the publication of that book. This past weekend was Boskone 49, a science fiction / fantasy literature convention down in South Boston. After great experiences at ReaderCon the past couple of years, I decided to head down and partake in the fun for the spring, hitting up a bunch of panels and getting to meet up with people that I've largely talked to online over the past couple of years.

This past weekend was Boskone 49, a science fiction / fantasy literature convention down in South Boston. After great experiences at ReaderCon the past couple of years, I decided to head down and partake in the fun for the spring, hitting up a bunch of panels and getting to meet up with people that I've largely talked to online over the past couple of years.