Rick Atkinson & History

/

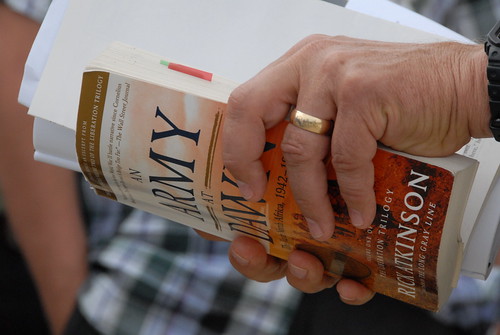

This summer’s entry in the Todd Lecture series at Norwich University was Pulitzer Prize winning author Rick Atkinson, former reporter for the Washington Post and author of several of books, most notably, An Army at Dawn, about the Invasion of Africa (which won him the Pulitzer in history), and more recently, The Day of Battle, about the invasion of Italy, both part of his epic trilogy on the events of the Invasion of Europe. In an already cluttered field of works on the Second World War in Europe, Atkinson’s books stand out immensely as some of the best books about the conflict, and the third book, of which he’s completed the research for, and is now outlining and writing, will be out in a couple of years, and will undoubtedly be a gripping read.

Atkinson spoke about an important and relevant topic to the history graduates before him: the value of narrative history, and more specifically, the need for a writer to recognize the value of a story within the heady analysis and synthesis of an argument. Personally, I find the division and outright snobbery of most academic circles to be frustrating, especially when it comes to popular and commercial non-history. Within history is a plethora of stories, values, themes and lessons to be breathed, learned and valued, and an essential part of education is bringing across the message to the reader or general audience in a way that they can comprehend and relate to the contents of any historical text.

Commercial nonfiction has its good and bad elements to it. Bringing anything to a general audience can water down an argument, and the balance between good stories and good history is one that has to be balanced finely. Some authors do this well, and from what I’ve read of Atkinson’s books, he has done just that.

Mainstream history is important. It is what helps to bring the lessons and analysis of the past to the people, and a population that reads and learns from their historians is a population that can intelligently call upon the past to make decisions for the future by comparing their current surroundings to similar happenings in the past. More than ever, this is important, and Atkinson’s talk and follow-up questions help to drive this point home.

Atkinson’s books are in the unique category of bridging the divide between academic and popular reading, and he noted that the failed to believe that history needed to be dry, uninteresting and irrelevant. History does not need to be relegated to only the academic circles, but it should be something that is in the foremost thoughts of the American population.

History is important, not just because of the lessons that are learned from it, but because of the mindset that is required to comprehend it. History is not a record of events gone past, but of the interpretation and story that those events tell. What is required from those who examine the field is an understanding of how a large number of events, political and societal movements and individuals all come together in a sort of perfect storm to create the past. Much of this is cause and effect, and contrary to popular belief, the past holds no answers for the future: it is the understanding of how said events occur, within their individual contexts that allow for the proper mindset to understand how similar happenings might happen in the future and how to prepare for what is to come.

Atkinson’s talk was a good one for students to hear, and different approaches to history are simply the nature of the field. The Military History students who graduated last week were ones that have a large number of options open to them, and Atkinson’s talk (and his own stature as a historian) demonstrated that a doctorate isn’t the only way to make a living at this.

You can watch Mr. Atkinson's talk here.