The Untimely Death of Robert E. Howard

/ Back in April, I had been doing some reading on the Lovecraft Circle, and came across an interesting fact about one of the authors, Robert Howard. At the age of 30, he killed himself upon learning that his mother was in a coma and would never wake up again. It was interesting, because before that time, he had created a couple of well known characters, namely, Conan the Conqueror one of the pulp era's defining heroes. A couple of weeks ago, I came across one of his more Lovecraftian stories, The Black Stone, and was reminded of his short life and influence. Beyond just Conan, he helped to influence an entire subgenre of fantasy, Sword and Sorcery.

Back in April, I had been doing some reading on the Lovecraft Circle, and came across an interesting fact about one of the authors, Robert Howard. At the age of 30, he killed himself upon learning that his mother was in a coma and would never wake up again. It was interesting, because before that time, he had created a couple of well known characters, namely, Conan the Conqueror one of the pulp era's defining heroes. A couple of weeks ago, I came across one of his more Lovecraftian stories, The Black Stone, and was reminded of his short life and influence. Beyond just Conan, he helped to influence an entire subgenre of fantasy, Sword and Sorcery.

Go read The Untimely Death of Robert E. Howard over on Kirkus Reviews.

Sources:

- The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction Paperback, Paul Allen Carter. This source had mentioned Howard at points, but what was really helpful was some information about Weird Tale's cover artist, and the general (split) attitudes towards Howard's stories and the artwork that accompanied them.

- Dark Valley Destiny: The Life of Robert E. Howard, by L. Sprague de Camp. This is the first definitive biography of Howard, although I've been told that there's points where it's to be taken with a grain of salt. There's some factual information that's apparently wrong, and de Camp spents a lot of time speculating on Howard's psyche, chiefly towards his sexuality and the role in which his mother played in his life. I'm sure there's some Freudian things going on here, but I don't know how much to buy it completely.

- American Fantastic Tales, Poe to the Pulps, edited by Peter Straub. As with other Library of America books, there's a short bio about Howard, as well as his story, The Black Stone.

- Echoes of Valor II, edited by Karl Edward Wagner. This anthology contains both fiction and some lengthly introductions. This particular one has some good information on Howard's stories.

I make it no secret that I really enjoy Military Science Fiction. It's been on my mind lately, as I'm in the middle of preparing an anthology of Military SF stories for launch. When I was in college, I studied History and eventually earned my master's in Military History, and I've found that the sub genre has been an interesting place to read and rant about.

I make it no secret that I really enjoy Military Science Fiction. It's been on my mind lately, as I'm in the middle of preparing an anthology of Military SF stories for launch. When I was in college, I studied History and eventually earned my master's in Military History, and I've found that the sub genre has been an interesting place to read and rant about. Earlier this week, Grandmaster Frederik Pohl passed away at the age of 93. He's the last of a major generation in the genre, and was a legendary contributor to science fiction from every possible direction. It's a great loss for Science Fiction.

Earlier this week, Grandmaster Frederik Pohl passed away at the age of 93. He's the last of a major generation in the genre, and was a legendary contributor to science fiction from every possible direction. It's a great loss for Science Fiction.

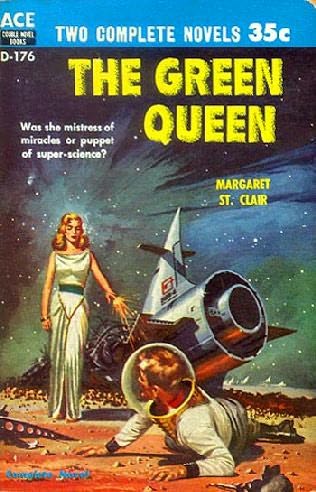

Science Fiction has a reputation as being the boy's club, where all the major names, such as Asimov, Heinlein and Clarke get a majority of the credit for the development and direction of the genre as a literary movement. It's unfortunate, because that's not the full story, and it means that there's a lot of other authors out there that really don't get the credit that they deserve.

Science Fiction has a reputation as being the boy's club, where all the major names, such as Asimov, Heinlein and Clarke get a majority of the credit for the development and direction of the genre as a literary movement. It's unfortunate, because that's not the full story, and it means that there's a lot of other authors out there that really don't get the credit that they deserve.

Lists are hard to do well. There's always too many entries, too much to say, and too short a space. For a while now, I've been wanting to do a survey of some of the notable dystopian stories, and following the news of Edward Snowden's leak of classified NSA program information, it seems like a good time to take a look at some of the notable works where government overreaches. It's fitting, as 1984 has enjoyed considerable success in the last couple of weeks.

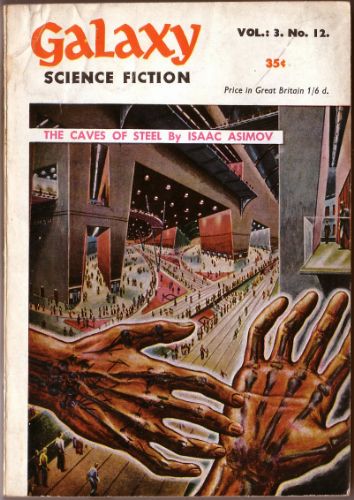

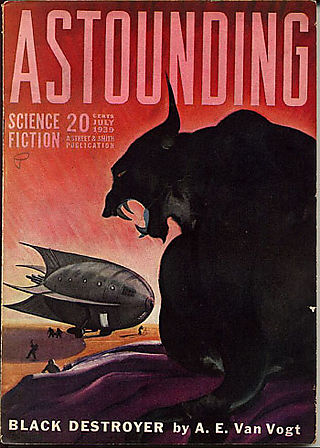

Lists are hard to do well. There's always too many entries, too much to say, and too short a space. For a while now, I've been wanting to do a survey of some of the notable dystopian stories, and following the news of Edward Snowden's leak of classified NSA program information, it seems like a good time to take a look at some of the notable works where government overreaches. It's fitting, as 1984 has enjoyed considerable success in the last couple of weeks. One of the things that I've really loved about this column is getting a sense of how connected everyone was. Truly, everyone seemed to know one another, even as small groups formed around certain editors. A case in point, over the last couple of columns, I've been looking at the Golden Age of SF, which is generally regarded as beginning with John W. Campbell Jr.'s rein at Astounding. Campbell's star was bright and enduring, but it lost its innovative edge. H.L. Gold, I think, deserves more attention for his role during the Golden Age, as his magazine Galaxy Science Fiction provided some of the genre's most enduring classics.

One of the things that I've really loved about this column is getting a sense of how connected everyone was. Truly, everyone seemed to know one another, even as small groups formed around certain editors. A case in point, over the last couple of columns, I've been looking at the Golden Age of SF, which is generally regarded as beginning with John W. Campbell Jr.'s rein at Astounding. Campbell's star was bright and enduring, but it lost its innovative edge. H.L. Gold, I think, deserves more attention for his role during the Golden Age, as his magazine Galaxy Science Fiction provided some of the genre's most enduring classics. Earlier this week, SF Grandmaster Jack Vance passed away at the age of 96. His writing career lasted over six decades, and he's known for his fantastic worldbuilding in addition to his enormous volume of works.

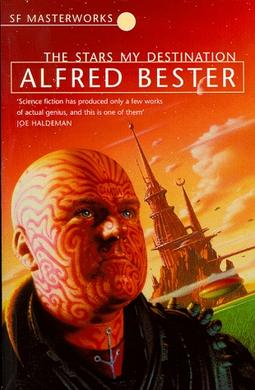

Earlier this week, SF Grandmaster Jack Vance passed away at the age of 96. His writing career lasted over six decades, and he's known for his fantastic worldbuilding in addition to his enormous volume of works. Last year, I picked up and read The Stars My Destination for the first time. It's an astonishing book, one that I alternatively wish that I'd read it earlier, and that I'm glad that I read it now, with the capabilities to really get how important of a book it is. The book was used in a science fiction class that I sat in on this past semester here at Norwich, and it was interesting to see the student's reactions to it.

Last year, I picked up and read The Stars My Destination for the first time. It's an astonishing book, one that I alternatively wish that I'd read it earlier, and that I'm glad that I read it now, with the capabilities to really get how important of a book it is. The book was used in a science fiction class that I sat in on this past semester here at Norwich, and it was interesting to see the student's reactions to it.

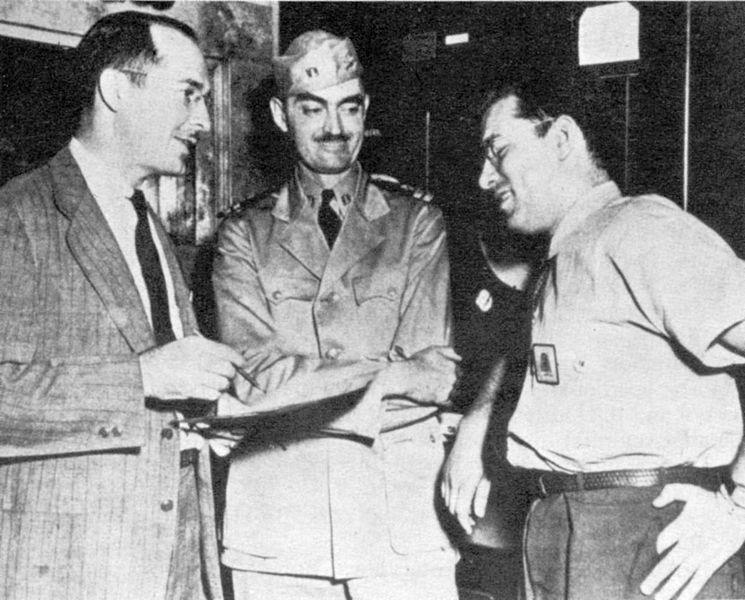

One of the things that I've found distinctly interesting about the Golden Age of SF is how the authors shape the field that they're in, but also how much one can extrapolate a larger picture out of an author's life. An excellent example of this is Judith Merril, through whom one can find an excellent viewpoint of the shifts in publishing, as well as a number of similarly-high-profiled authors writing at the same time. This is the first of probably a couple of posts about Merril - her career as a whole will likely require more space. Indeed, the Futurians themselves warrant a couple of posts of their own.

One of the things that I've found distinctly interesting about the Golden Age of SF is how the authors shape the field that they're in, but also how much one can extrapolate a larger picture out of an author's life. An excellent example of this is Judith Merril, through whom one can find an excellent viewpoint of the shifts in publishing, as well as a number of similarly-high-profiled authors writing at the same time. This is the first of probably a couple of posts about Merril - her career as a whole will likely require more space. Indeed, the Futurians themselves warrant a couple of posts of their own.

I came across something interesting in the last couple of years: The best of the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, was written by a longtime SF author, Leigh Brackett, who had written the film's first draft before passing away. When I had been

I came across something interesting in the last couple of years: The best of the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, was written by a longtime SF author, Leigh Brackett, who had written the film's first draft before passing away. When I had been

Last year, I largely covered the formation of the Science Fiction genre, going from some of the notable early authors, and running up to the pulp era. There's a lot that I haven't covered, and at some point, I'm going to be going back and filling in some of the holes behind me. There's an enormous number of authors and editors out there, and there's always going to be new things to add and explore.

Last year, I largely covered the formation of the Science Fiction genre, going from some of the notable early authors, and running up to the pulp era. There's a lot that I haven't covered, and at some point, I'm going to be going back and filling in some of the holes behind me. There's an enormous number of authors and editors out there, and there's always going to be new things to add and explore. Women are vastly underrepresented in science fiction circles, especially back in the pulp days. While many point to

Women are vastly underrepresented in science fiction circles, especially back in the pulp days. While many point to  For my last Kirkus Column, I talked about

For my last Kirkus Column, I talked about  I got into science fiction through my love of Star Wars. The geeky primer had already been charged with earlier stories, but George Lucas's films pushed my geeky little mind into overdrive.

I got into science fiction through my love of Star Wars. The geeky primer had already been charged with earlier stories, but George Lucas's films pushed my geeky little mind into overdrive.