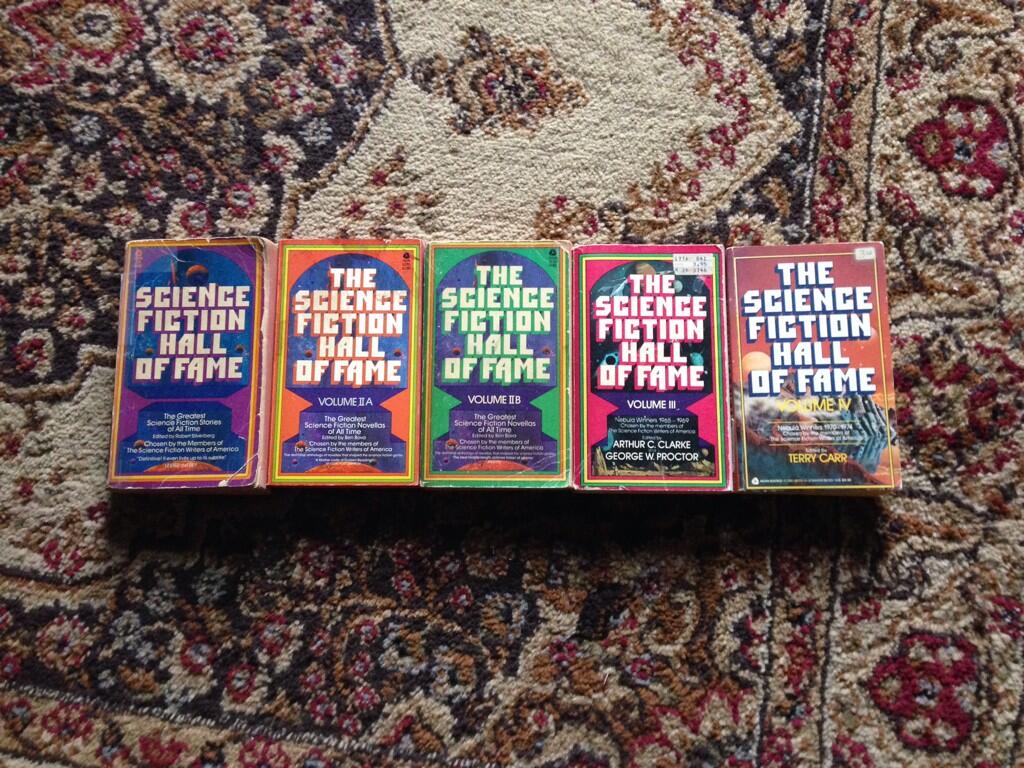

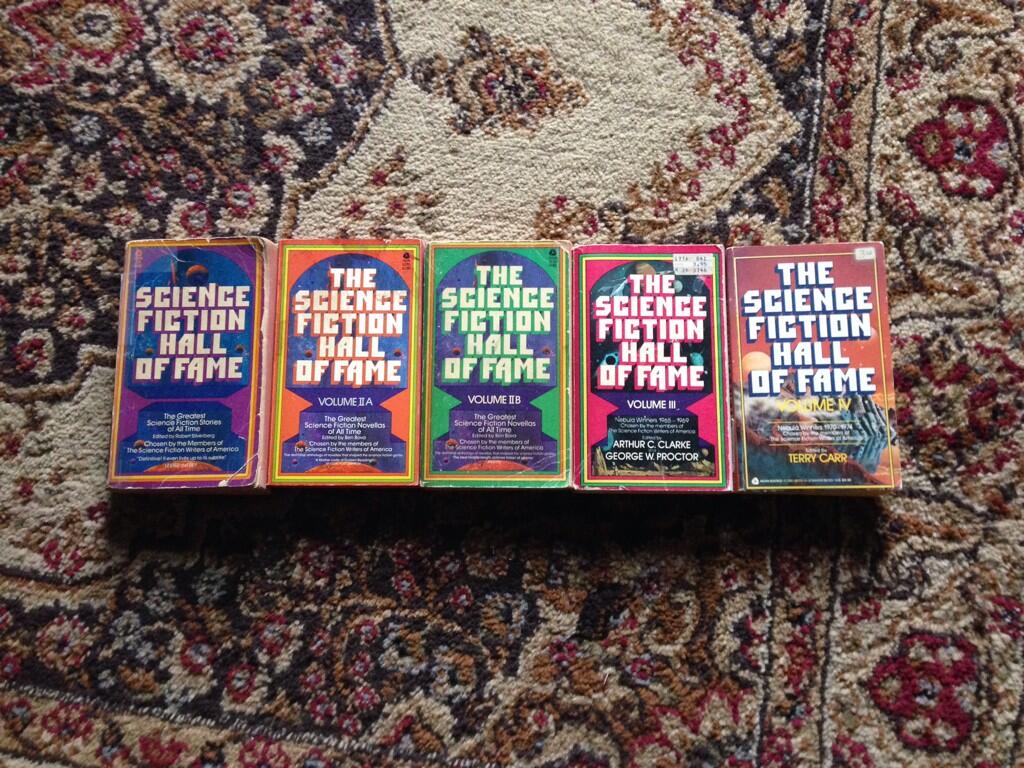

I started reading SF when I was in High School, and was supported by the school's librarian, Sylvia Allen, who encouraged me to pick up new works. At one point, someone had donated a treasure trove of Science Fiction novels to the school, a lot of which they couldn't catalog, due to age and space. A lot of them went up for sale, and she let me have a crack at them early. One of the books in the pile was The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 1, which contained a story from an author I'd been reading, Isaac Asimov, and a number of others. I took it home, and was immediately hooked.

I started reading SF when I was in High School, and was supported by the school's librarian, Sylvia Allen, who encouraged me to pick up new works. At one point, someone had donated a treasure trove of Science Fiction novels to the school, a lot of which they couldn't catalog, due to age and space. A lot of them went up for sale, and she let me have a crack at them early. One of the books in the pile was The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 1, which contained a story from an author I'd been reading, Isaac Asimov, and a number of others. I took it home, and was immediately hooked.

A couple of years later, when I worked at the Brown Public Library in Northfield, I had struck up a friendship with an older patron who (if I remember correctly) had been connected to fandom in New York City. He recounted several stories of authors such as Walter Miller Jr. and a couple of others. At one point, I mentioned the anthology that I'd been re-reading, and he told me that there were two others, and ended up bringing them in for me to have. Later, I bought the re-released version of the first volume, so as to relieve my old copy of wear and tear that it desperately didn't need.

For years, I thought that the three books were the only ones. It wasn't until I started seeing the title pop up in my research that I started to look deeper into the anthology, and to my surprise, found that two others had been printed in the 1980s, but which had been largely forgotten.

The anthologies have a curious history, and never would have come about but for the creation of the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) and some of their financial troubles. For those interested in science fiction history, the focus of the books are a nice match: the first three volumes were explicitly put together with the idea of charting the evolution of the genre. While they're incomplete (two women in the entire book - I'm really sad that there wasn't a Moore Northwest Smith story in there, or anything by Francis Stevens) by modern standards, it's pretty much the entire Golden Age of SF in a single book. In and of themselves, they are a historical curiosity, and an interesting read all together - a lot of the stories still hold up nicely.

Go read SFWA and the 'Science Fiction Hall of Fame' Anthologies over on Kirkus Reviews.

Sources:

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 1, Robert Silverberg. Silverberg's introduction has a lot of detail about how this project came about, and it's worth a read into the work and background for this.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 2A/B, Ben Bova. Bova's introduction also provides some good details on his entry.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 3, Arthur C. Clarke. Clarke's introduction here isn't all that useful, but it does show a pivot for the anthology: a focus now on Nebula winners, rather than historical works. What I found interesting here was also that it's the first book in the series not published by Doubleday.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 4, Terry Carr. As with Clarke's introduction, there's more an emphaisis on the Nebula designation rather than on the selection.

SFWA Bulletin, December 1967: I was able to get a scan of the original Bulletin that issued the call for stories.

SF Encyclopedia:

Damon Knight: Damon Knight's biography of the Futurians doesn't mention this, but the SFE3 entry provides some good details into this time of his life.

SFWA: This has some good backstory on SFWA's formation.

Nebula Award: Similarly, this provides some good background information.

ISFDB Entry - Science Fiction Hall of Fame: This was particularly helpful in figuring out publication dates and publishers.

Huge thanks to Former SFWA president Michael Capobianco and Robert Silverberg for their help with this one.

One of my favorite books is easily A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L'Engle. I can't remember when I first read it, but when I went back to it a couple of years ago, I was struck by its prose and outstanding story.

One of my favorite books is easily A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L'Engle. I can't remember when I first read it, but when I went back to it a couple of years ago, I was struck by its prose and outstanding story.

A couple of years ago, I picked up a book to

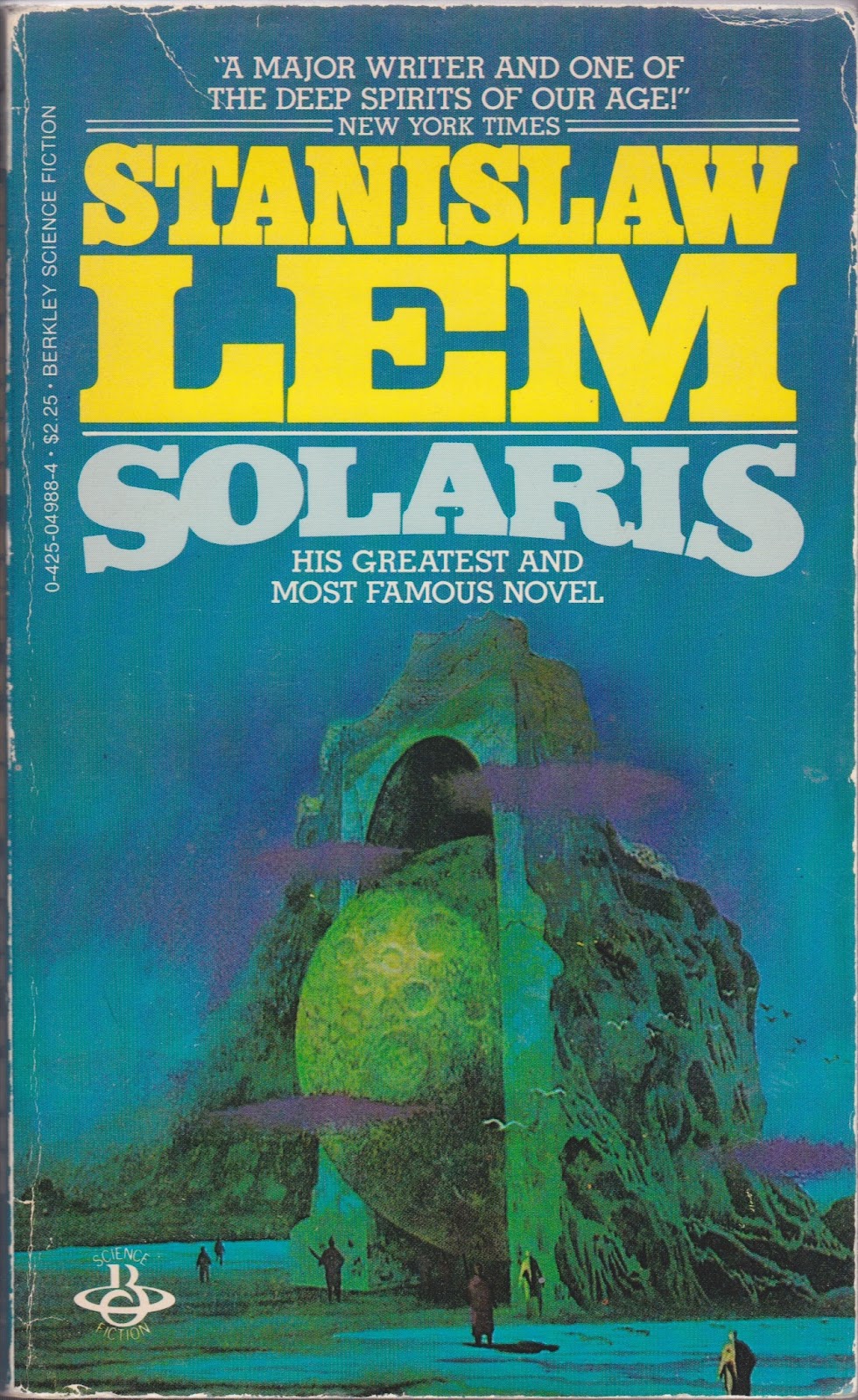

A couple of years ago, I picked up a book to  Almost ten years ago now, I picked up a copy of Stanislaw Lem's novel Solaris and was struck at how different it was compared to a number of the other books I was reading at the time. It was an interesting and probing novel, one that I don't think I fully understood at the time. (I still don't).

Almost ten years ago now, I picked up a copy of Stanislaw Lem's novel Solaris and was struck at how different it was compared to a number of the other books I was reading at the time. It was an interesting and probing novel, one that I don't think I fully understood at the time. (I still don't). Ursula K. Le Guin is one of science fiction's greats: her stories Left Hand of Darkness, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Dispossessed rank among the genre's best works, and she moves easily between science fiction and fantasy, writing things that science fiction authors had barely touched before she came onto the scene. To say she was influential is to undersell one's words.

Ursula K. Le Guin is one of science fiction's greats: her stories Left Hand of Darkness, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Dispossessed rank among the genre's best works, and she moves easily between science fiction and fantasy, writing things that science fiction authors had barely touched before she came onto the scene. To say she was influential is to undersell one's words.

One of the first major SF novels that I picked up was Dune. Something about the copy at the library was striking: a figure against a desert. I tore into it and to this day, I can still visualize various parts of the book. It got me thinking about science fiction in ways that I hadn't before, and I still count it as one of my favorite books. I've never read the sequels: I never wanted to be disappointed or let down by the other novels (much like I've never read the 2nd and 3rd installments of the Ringworld and Foundation trilogies).

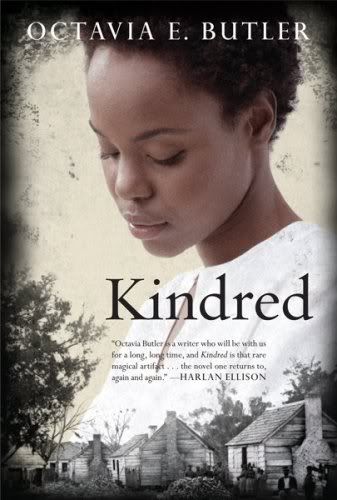

One of the first major SF novels that I picked up was Dune. Something about the copy at the library was striking: a figure against a desert. I tore into it and to this day, I can still visualize various parts of the book. It got me thinking about science fiction in ways that I hadn't before, and I still count it as one of my favorite books. I've never read the sequels: I never wanted to be disappointed or let down by the other novels (much like I've never read the 2nd and 3rd installments of the Ringworld and Foundation trilogies). For years, I've had friends tell me that I should be reading Octavia Butler's works, especially Kindred. I actually own a copy, and it's been sitting on my shelves for years, waiting for me to pick it up. When it came to the point where I'd start writing about the 1970s, it was pretty clear that Butler would be one of the authors that I'd be covering, and I picked up the book as part of my research. She's a powerful author, and I'm a little sad that I didn't read the book earlier. Researching Butler's life is fascinating, and it's becoming clear to me that some of the genre's most important works emerge from outside of it's walls.

For years, I've had friends tell me that I should be reading Octavia Butler's works, especially Kindred. I actually own a copy, and it's been sitting on my shelves for years, waiting for me to pick it up. When it came to the point where I'd start writing about the 1970s, it was pretty clear that Butler would be one of the authors that I'd be covering, and I picked up the book as part of my research. She's a powerful author, and I'm a little sad that I didn't read the book earlier. Researching Butler's life is fascinating, and it's becoming clear to me that some of the genre's most important works emerge from outside of it's walls. Ringworld is a novel that's always stuck with me. I picked it up alongside authors such as Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Robert Heinlein, and other authors from that point in time. Foundation and Dune are two books that are among my favorites, but Ringworld has long been the best of the lot. It's vivid, funny, exciting and so forth. Reading it again recently in preparation for this column, I was astounded at how well it's held up (as opposed to Foundation) in the years since it's publication, and I can't wait to read it again. Plus, that cover is just beautiful.

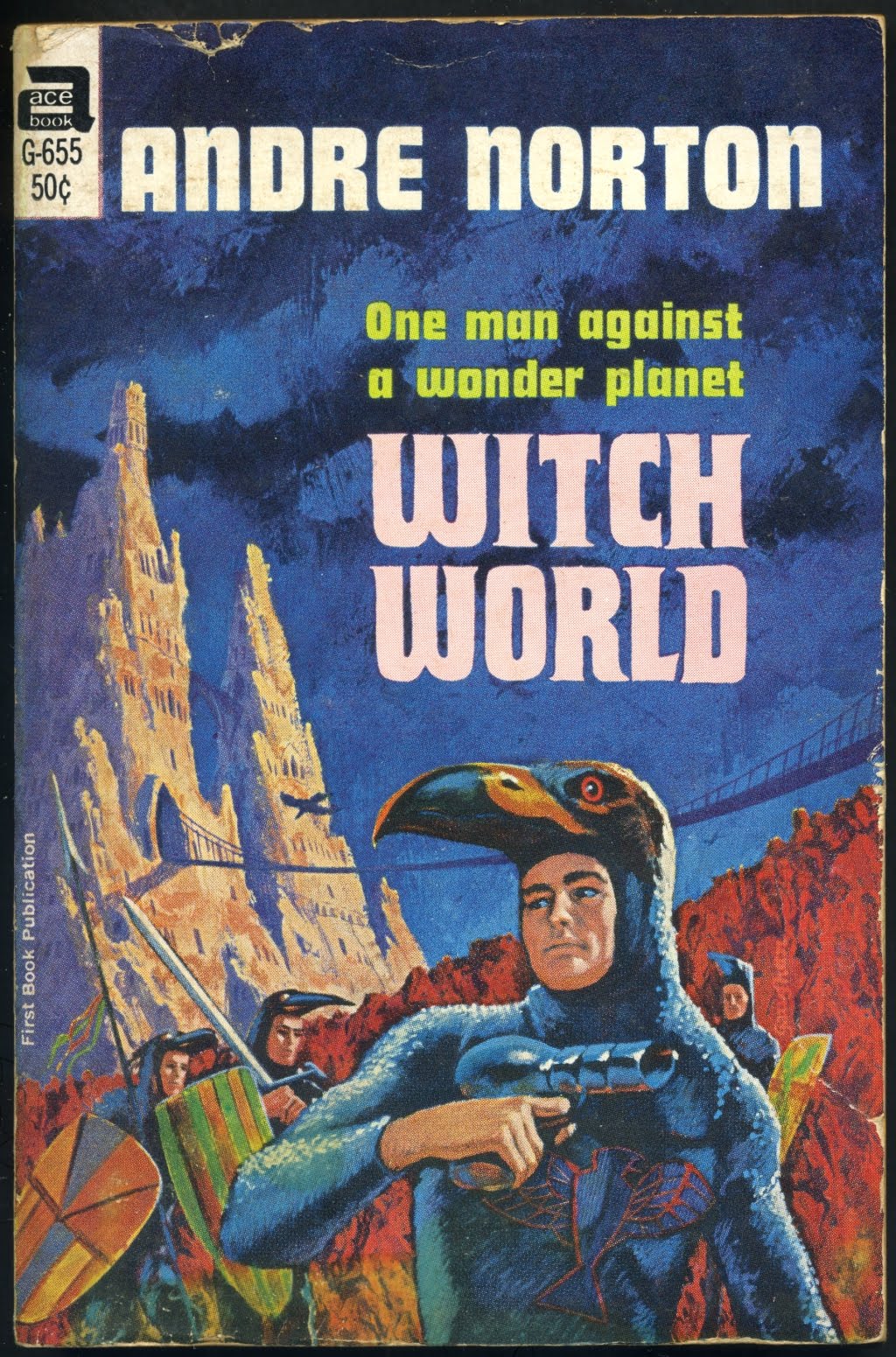

Ringworld is a novel that's always stuck with me. I picked it up alongside authors such as Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Robert Heinlein, and other authors from that point in time. Foundation and Dune are two books that are among my favorites, but Ringworld has long been the best of the lot. It's vivid, funny, exciting and so forth. Reading it again recently in preparation for this column, I was astounded at how well it's held up (as opposed to Foundation) in the years since it's publication, and I can't wait to read it again. Plus, that cover is just beautiful. When I worked at a bookstore (the now defunct Walden Books), I had a co-worker that loved Andre Norton. I'd never read any of her books throughout High School, although I was certainly familiar with her name. I wish now that I did.

When I worked at a bookstore (the now defunct Walden Books), I had a co-worker that loved Andre Norton. I'd never read any of her books throughout High School, although I was certainly familiar with her name. I wish now that I did. As I've been writing this column, I've realized that there's points where I have to move ahead and skip authors, or, after some reflection, research and writing, that I missed someone critical. Over the last couple of months, I've been realizing that not covering L. Frank Baum has been a drastic oversight, and that at the next available opportunity, I need to cover him and his wonderful world of Oz.

As I've been writing this column, I've realized that there's points where I have to move ahead and skip authors, or, after some reflection, research and writing, that I missed someone critical. Over the last couple of months, I've been realizing that not covering L. Frank Baum has been a drastic oversight, and that at the next available opportunity, I need to cover him and his wonderful world of Oz.

I've had a passing fascination with McCaffrey's books over the years, even as I never really dabbled in them. (I owned one book, Dragonflight, years ago.) I was always somewhat intimidated by the sheer size and scale of the series, and I was always more interested in SF than I was Fantasy (although now, I realize that that was a bit misguided.) Anne McCaffrey was always an author I was aware of: one of the female authors alongside the Asimovs, Herberts and Heinleins in my high school library.

I've had a passing fascination with McCaffrey's books over the years, even as I never really dabbled in them. (I owned one book, Dragonflight, years ago.) I was always somewhat intimidated by the sheer size and scale of the series, and I was always more interested in SF than I was Fantasy (although now, I realize that that was a bit misguided.) Anne McCaffrey was always an author I was aware of: one of the female authors alongside the Asimovs, Herberts and Heinleins in my high school library. I've been a fan of Game of Thrones since I first caught it a couple of years ago, and I've been impressed with the HBO series as I've continued to watch. When Season 1 hit, I pulled out my copies of A Song of Ice and Fire and started the first book, alternatively reading and watching the show. I've found the books to be a trial to get through, but I've ultimately enjoyed them.

I've been a fan of Game of Thrones since I first caught it a couple of years ago, and I've been impressed with the HBO series as I've continued to watch. When Season 1 hit, I pulled out my copies of A Song of Ice and Fire and started the first book, alternatively reading and watching the show. I've found the books to be a trial to get through, but I've ultimately enjoyed them. In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history.

In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history. One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him.

One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him. When Megan and I started dating, I made the trip from Vermont to Pennsylvania. It's around eight hours, covering four states. On one such trip, I decided I really didn't want to endure New Jersey, and took an early exit off of I-87 toward the alluring sign 'Delaware Water Gap'. It didn't take me much longer to cut through the two-lane road, perfect for driving a Mini Cooper on, and it took me through a quiet, quaint looking town of Milford. Since Megan and I have married, we make the trip frequently, crossing through Milford a couple of times a year. I like the town, even though I've never stopped.

When Megan and I started dating, I made the trip from Vermont to Pennsylvania. It's around eight hours, covering four states. On one such trip, I decided I really didn't want to endure New Jersey, and took an early exit off of I-87 toward the alluring sign 'Delaware Water Gap'. It didn't take me much longer to cut through the two-lane road, perfect for driving a Mini Cooper on, and it took me through a quiet, quaint looking town of Milford. Since Megan and I have married, we make the trip frequently, crossing through Milford a couple of times a year. I like the town, even though I've never stopped. The first Blish story I read was Surface Tension in Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology. While there's certainly some issues with the anthology, it's a solid collection of short fiction. Blish isn't an author I've read extensively, but I remember him popping up frequently in the various anthologies I read over the years.

The first Blish story I read was Surface Tension in Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology. While there's certainly some issues with the anthology, it's a solid collection of short fiction. Blish isn't an author I've read extensively, but I remember him popping up frequently in the various anthologies I read over the years. There were two authors I read extensively when I first started reading science fiction. The first was Isaac Asimov, because, well. Robots. Foundation. Reasons. The other was Arthur C. Clarke. The first story I really remember reading from him came from a thick anthology cultivated by Asimov, with one fantastic story by Clarke in it: Who's There? I then ran through a bunch of his books: 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010, 2061 and 3001 are the ones I checked out over and over again. Later, I dug into Rama and even later, Childhood's End.

There were two authors I read extensively when I first started reading science fiction. The first was Isaac Asimov, because, well. Robots. Foundation. Reasons. The other was Arthur C. Clarke. The first story I really remember reading from him came from a thick anthology cultivated by Asimov, with one fantastic story by Clarke in it: Who's There? I then ran through a bunch of his books: 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010, 2061 and 3001 are the ones I checked out over and over again. Later, I dug into Rama and even later, Childhood's End.