A while ago, I wrote about Joe Haldeman and his debut novel The Forever War, and promised to post up our conversation. Here it is:

Andrew Liptak: What can you tell me about how you first came across science fiction? What do you first remember reading, and what made you stick with the genre?

A while ago, I wrote about Joe Haldeman and his debut novel The Forever War, and promised to post up our conversation. Here it is:

Andrew Liptak: What can you tell me about how you first came across science fiction? What do you first remember reading, and what made you stick with the genre?

Joe Haldeman: The first sf book I read was the Winston Juvenile ROCKET JOCKEY, by Philip St. John (pen name of Lester del Rey). My teacher caught me reading in class and took the book away – but then returned it with the admonition not to read in class, and loaned me a bunch of other YA science fiction, from her daughter's collection.

Why did I stick with the genre? There was nothing else like it. It totally captivated me, and in fact I resisted the teachers and librarians who tried to interest me in other books.

AL: I've read that you traveled quite a bit as a child - how did that impact how you viewed the world? Did this impact your writing?

JH: I suppose it must have affected my writing, because "home" was rather a plastic designation; I lived five places in my first seven years. The huge wild beauty of Alaska might have made the unearthly more accessible to me than it would have been to a child who grew up in a more prosaic place.

AL: You attended University of Maryland, where you studied physics and astronomy. Was it your interest in the subject that brought you to science fiction, or the other way around?

JH: My interest in sf and astronomy grew simultaneously, at least through my mid-teens; I didn't think of them separately until I was older.

AL: Following your graduation from college, you were drafted into the Army. What were your feelings on the Vietnam War at that point?

JH: I was against it – certainly against my being in it! I was a pacifist by natural inclination, but knew that pacifism didn't make sense to other people. (Of course the status of a draft-age pacifist is necessarily ambiguous. He may just not want to die or lose precious parts.)

AL: What was Basic like after graduating from college?

JH: I was the only college graduate in my company, and also the oldest man. I got some grudging respect from the others for both things.

None of them read science fiction, of course; most of them either couldn't read or found reading difficult. Only two other guys read for pleasure.

I must say more than that, though. These illiterate men had a very high regard for the books they couldn't read. That's not meant to be ironic.

And I learned invaluable things from them. Not being able to read is a handicap, but it doesn't make you subhuman. I was astonished (in my naiveté) at how much we had in common.

AL: Do any of them appear in your books?

JH: I took the protagonist's name Farmer in WAR YEAR from a friend who was in my platoon in Vietnam. The character in the story looks like the real person and has a similar background.

AL: What can you tell me about being shipped out to Vietnam? Your biography on your website states that you were assigned to the 4th Division. What was your job here?

JH: I was made a combat engineer (pioneer), but that doesn't have much to do with engineering as a professional or academic discipline. What we repeated to each other, wryly, was that engineers were too dumb for the infantry, so they gave us a shovel rather than a gun. (Of course we did have guns, in every variety, but I used the pick and shovel more often.)

AL: How did you experience the war?

JH: I sort of passed through it like a very realistic nightmare. Badly injured, I stayed in Vietnam, rather than returning stateside, because of a clerical error (though I was mostly out of combat those five months – only three enemy attacks).

AL: What can you tell me about your injuries?

JH: One big bullet wound in the upper thigh, a .51 caliber machine-gun round that was part of a booby trap. At the same time I absorbed about twenty large shrapnel wounds and perhaps a hundred smaller ones. Five of those impacted my testicles, and gave me as much trouble as the bullet.

AL: Your first story was 'Out of Phase', published by Galaxy Magazine in 1968. What prompted you to start writing science fiction?

JH: I was writing science fiction (in the form of long comic strips) in the fourth grade. Never stopped.

AL: Your first novel was titled War Year, about your experiences. Why write a fictional account of your experiences, rather than a memoir or history?

JH: I saw myself as a fiction writer. WAR YEAR is a slightly fictionalized memoir. It seemed like the natural approach. I wrote up an outline and a couple of sample chapters (with Ben Bova's encouragement) and sold it to the first publisher who saw it. Most of the action and descriptions are copied from the daily letters I wrote home to my wife while I was in Vietnam, combat and then hospitals.

AL: The novel you're best known for is your debut SF title, The Forever War, written at the Iowa Writer's Workshop, where you got your MFA. Where did this story first appear from?

JH: It came out of a series of novelettes and novellas that were published in Analog magazine. (Actually, it was written as a coherent novel, and dissected into episodes for the magazine. Makes it an "episodic" novel, but so what?)

AL: Sorry, I think that I phrased that poorly: where did you come up with the idea for William Mandela and the plot of The Forever War?

JH: He was almost purely autobiographical. The plot of THE FOREVER WAR grew out of the novelette "Hero," which was just a science-fictional translation of my experiences in Vietnam, plus some cool aliens.

AL: How much of your experiences in Vietnam inspired The Forever War?

JH: Almost all of it. I wouldn't have even thought of writing the book if I hadn't been a soldier.

AL: A lot's been made of its connections to Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers and how you felt it was a work that glorified war. Do you write The Forever War as an anti-war novel?

JH: Of course it was an anti-war novel, but it wasn't an "answer" to STARSHIP TROOPERS, as some people claimed. Novels aren't conversations. I liked STARSHIP TROOPERS for what it was, a quickly written didactic novel with some great action scenes.

AL: What did Heinlein think of The Forever War?

JH: He liked it very much. When we met, he told me he had read it three times.

AL: The Forever War was written as a sort of thesis for your MFA program? I take it you passed? ;)

JH: Easily. I don't think anyone who actually finished a book did not get his or her degree, while I was at Iowa. (Not unusual for MFA's, anywhere.)

AL: What did your instructors think about the book? Was there any question about genre or encouragement to steer clear of SF?

JH: My advisor, Vance Bourjaily, liked it very much, and really, his opinion was the only one that mattered. The professor in charge of the department, Jack Leggett, and one senior professor, Stanley Elkin, detested any science fiction – or genre fiction of any description, for that matter. But Vance liked it very much (partly as a fellow combat veteran), and we became friends.

Stephen Becker, another senior professor, really liked my work, and I loved his. A few years later, I went out to Tortola to collaborate on a novel with him. We had a good time, but couldn't make the novel cohere.

AL: Once the book was written, what was the sales process like?

JH: (for WAR YEAR) Almost invisible. Holt didn't know what to do with it, so it didn't do anything. One ad, about an inch square in Publishers Weekly.

It got a full-page review in The New York Times, but Holt never followed up on that. The advertising budget was less than a thousand dollars.

Maybe this was the low point of my career: Right after WAR YEAR came out, I went to the annual publishers' convention in Washington, D.C. I had borrowed an editor's name tag, and so was anonymous when I went to the Holt, Rinehart and Winston table. They had a copy of WAR YEAR there, and I asked the salesman about it. He said he'd read it and thought it was a good book, but they weren't pushing it. "It's about Viet Nam," he said, "so nobody's gonna read it." So I slunk out radiating despair.

(For THE FOREVER WAR -- It got a small positive review in the New York Times – as a mainstream book, not science fiction. I think that helped quite a bit. In those days the NYTBR did have a science fiction column, but it was definitely treated as a poor relation, compared to things that were published in the main part of the book.)

AL: I heard that you first sold The Forever War to Terry Carr at Ace Books. What happened with that?

JH: Terry got fired and was told to take his books with him.

AL: The Forever War was also serialized in Analog (I have a copy with ‘Hero’ in it!): what was the reception like in the fan community as that was being released?

JH: What I remember is that everybody loved it. That's probably not true, but it's what I remember.

AL: What was your reaction to the number of awards that it began to win in the mid-70s?

JH: I was surprised. Now I'm less surprised.

I knew I was a good writer then, but I was surrounded by good writers who weren't making a living. Now I know that if a person is a good writer, success may come from a combination of luck and talent -- or it may not. I had enough of both, and good timing along with the luck.

Seventeen publishers turned down THE FOREVER WAR, usually with the explanation given above – good book but nobody will touch it. The eighteenth, Tom Dunne at St. Martin's Press, decided to take a chance. That made all the difference.

AL: Nobody would publish the novel because it was about Vietnam?

JH: Right. Vietnam novels were un-sellable.

AL: The book has consistently been named as one of the best SF novels out there since it’s publication: do you think that it’s become more relevant since the US has been engaged in the Middle East?

JH: Maybe so, but that doesn't have anything to do with my intentions – except that one war is much like another, from the ground-pounder's point of view.

AL: What has the reaction been like from the veteran / soldier community?

JH: Soldiers and veterans have been very positive about the book, though I suspect that a large part of that is people not saying anything if they didn't like it. Criticizing a disabled veteran, after all.

Last year, I was shocked to read that Iain M. Banks announced that he had cancer and was going to die within months. I had first come across him when I picked up Consider Phlebas, and several of its sequels when my Waldenbooks shut down and liquidated its stock: his books were amongst the first that I grabbed and stuck in the backroom to hold while we waited for the store to close. I really enjoyed the novel, although I've yet to really pick up any of the others. I was facinated by the depth and breadth of the Culture.

Last year, I was shocked to read that Iain M. Banks announced that he had cancer and was going to die within months. I had first come across him when I picked up Consider Phlebas, and several of its sequels when my Waldenbooks shut down and liquidated its stock: his books were amongst the first that I grabbed and stuck in the backroom to hold while we waited for the store to close. I really enjoyed the novel, although I've yet to really pick up any of the others. I was facinated by the depth and breadth of the Culture.

C.J. Cherryh is an author that I've come across quite a lot, but was never one that I really ever got into. Recently, I've become more interested in her books, particularly Downbelow Station, which prompted me to take a look at her career. It's a facinating one that pulls in some of the legacies of her predecessors (such as Robert Heinlein and similar), and newer innovations that made her career different than that of her predecessors: she was primarily a novelist, rather than someone who started in the pulp magazines.

C.J. Cherryh is an author that I've come across quite a lot, but was never one that I really ever got into. Recently, I've become more interested in her books, particularly Downbelow Station, which prompted me to take a look at her career. It's a facinating one that pulls in some of the legacies of her predecessors (such as Robert Heinlein and similar), and newer innovations that made her career different than that of her predecessors: she was primarily a novelist, rather than someone who started in the pulp magazines.

Joanna Russ wasn't an author I came across when I first came across science fiction: she was someone that I slowly became aware of more recently, when I started working at this on a more professional and critical level. Part of this came from friends who were interested and researching her, and over the last couple of years, I've gained an appreciation for the few works that I have read.

Joanna Russ wasn't an author I came across when I first came across science fiction: she was someone that I slowly became aware of more recently, when I started working at this on a more professional and critical level. Part of this came from friends who were interested and researching her, and over the last couple of years, I've gained an appreciation for the few works that I have read.

I picked up this book the other day: reading up on the ongoing West African Ebola Outbreak has become a focus of research and interest of mine lately. My interests in Ebola go back to the granddaddy of all Ebola books: The Hot Zone, by Richard Preston, published back in the mid-90s, and read while I was in Middle or High School. It's been one of those things that's sort of been at the back of my mind in the intervening years, with an assumption that at some point (not an IF), it'll break out into a wider population and cause some real harm. That's what's happened for almost a year now over in West Africa.

I picked up this book the other day: reading up on the ongoing West African Ebola Outbreak has become a focus of research and interest of mine lately. My interests in Ebola go back to the granddaddy of all Ebola books: The Hot Zone, by Richard Preston, published back in the mid-90s, and read while I was in Middle or High School. It's been one of those things that's sort of been at the back of my mind in the intervening years, with an assumption that at some point (not an IF), it'll break out into a wider population and cause some real harm. That's what's happened for almost a year now over in West Africa.

Science Fiction publishing is full of strange characters, but there's one story that seems to really capture people's attention consistently: James Tiptree Jr., a brilliant figure who seemed to appear out of nowhere, earn a number of awards, and maintained a fairly elusive personality in science fiction circles. It wasn't until a decade of writing that it was revealed that Tiptree wasn't actually a guy: it was a woman named Alice Sheldon, with an utterly fascinating background: she had traveled the world, participated in the Second World War, worked for the CIA and had a PhD.

Science Fiction publishing is full of strange characters, but there's one story that seems to really capture people's attention consistently: James Tiptree Jr., a brilliant figure who seemed to appear out of nowhere, earn a number of awards, and maintained a fairly elusive personality in science fiction circles. It wasn't until a decade of writing that it was revealed that Tiptree wasn't actually a guy: it was a woman named Alice Sheldon, with an utterly fascinating background: she had traveled the world, participated in the Second World War, worked for the CIA and had a PhD. This was pretty cool: Seven Days, the local weekly paper here in Vermont, interviewed me last week about my work on War Stories, Geek Mountain State and the 501st New England Garrison.

This was pretty cool: Seven Days, the local weekly paper here in Vermont, interviewed me last week about my work on War Stories, Geek Mountain State and the 501st New England Garrison. At long last, War Stories: New Military Science Fiction is officially out in bookstores today! Co-edited by Jaym Gates and myself, the anthology takes a new look at warfare in science fiction, with the central focus of how the people who wage it and are caught up in it are impacted by the fighting.

At long last, War Stories: New Military Science Fiction is officially out in bookstores today! Co-edited by Jaym Gates and myself, the anthology takes a new look at warfare in science fiction, with the central focus of how the people who wage it and are caught up in it are impacted by the fighting. A week ago, my grandmother went to the hospital for surgery: she had an aneurysm that acted as a ticking time bomb, and doctors were reasonably sure that they could fix it with an experimental surgery, grafting some arteries together. I received text messages over the course of the day from my sister. The projected seven-hour affair stretched into ten then twelve and finally, fourteen hours before everything was completed.

A week ago, my grandmother went to the hospital for surgery: she had an aneurysm that acted as a ticking time bomb, and doctors were reasonably sure that they could fix it with an experimental surgery, grafting some arteries together. I received text messages over the course of the day from my sister. The projected seven-hour affair stretched into ten then twelve and finally, fourteen hours before everything was completed. A while ago,

A while ago,  I'm happy to say that I am now represented by Kelli Christiansen of

I'm happy to say that I am now represented by Kelli Christiansen of  One of my favorite books is easily A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L'Engle. I can't remember when I first read it, but when I went back to it a couple of years ago, I was struck by its prose and outstanding story.

One of my favorite books is easily A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L'Engle. I can't remember when I first read it, but when I went back to it a couple of years ago, I was struck by its prose and outstanding story. A couple of years ago, I picked up a book to

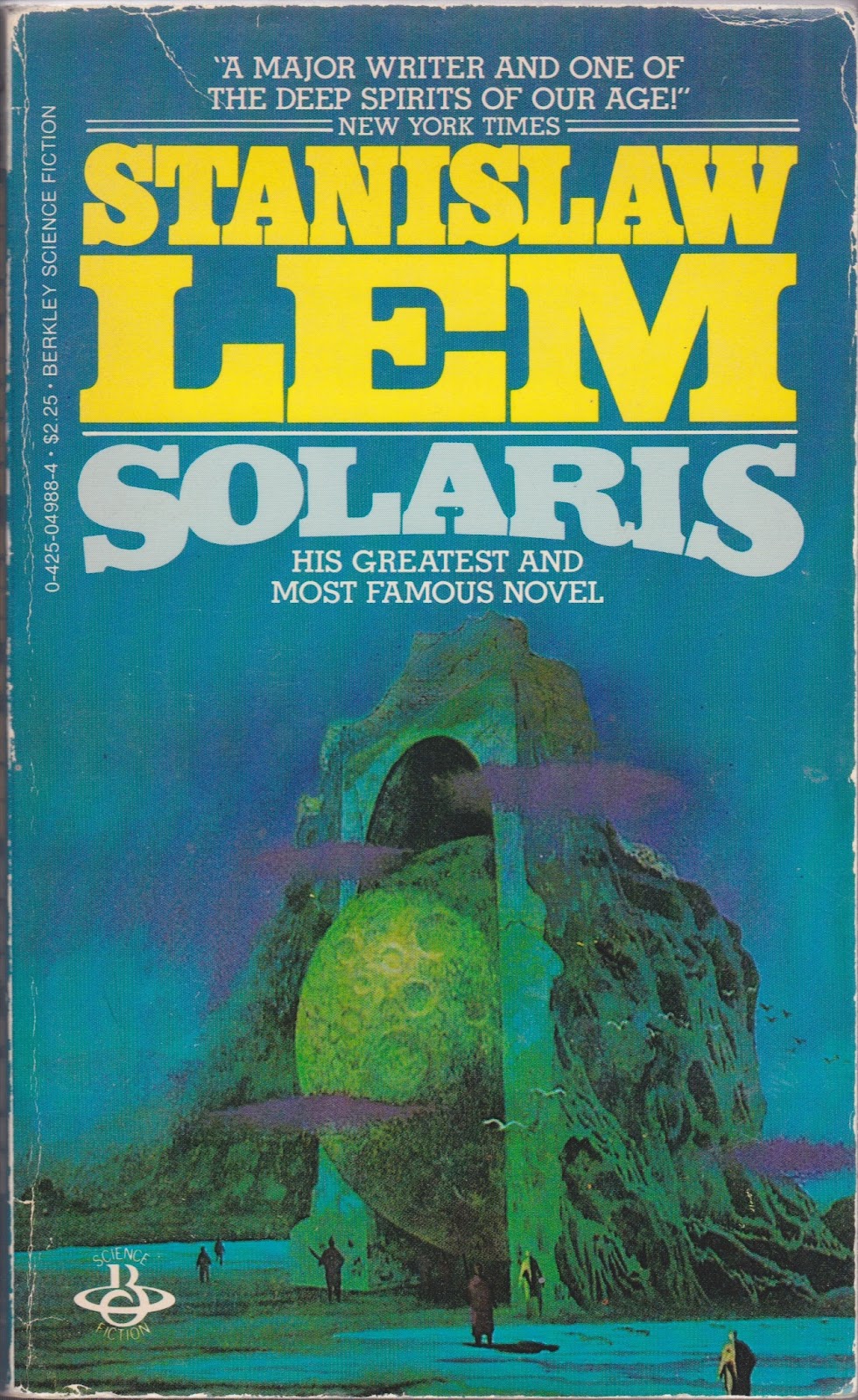

A couple of years ago, I picked up a book to  Almost ten years ago now, I picked up a copy of Stanislaw Lem's novel Solaris and was struck at how different it was compared to a number of the other books I was reading at the time. It was an interesting and probing novel, one that I don't think I fully understood at the time. (I still don't).

Almost ten years ago now, I picked up a copy of Stanislaw Lem's novel Solaris and was struck at how different it was compared to a number of the other books I was reading at the time. It was an interesting and probing novel, one that I don't think I fully understood at the time. (I still don't). Ursula K. Le Guin is one of science fiction's greats: her stories Left Hand of Darkness, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Dispossessed rank among the genre's best works, and she moves easily between science fiction and fantasy, writing things that science fiction authors had barely touched before she came onto the scene. To say she was influential is to undersell one's words.

Ursula K. Le Guin is one of science fiction's greats: her stories Left Hand of Darkness, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Dispossessed rank among the genre's best works, and she moves easily between science fiction and fantasy, writing things that science fiction authors had barely touched before she came onto the scene. To say she was influential is to undersell one's words.