Amongst one of the many books that has come highly recommended to me, especially from my fellow graduate students, was Joe Haldeman's The Forever War. Published in 1974, Haldeman's book is an interesting one, tying together a stiff criticism for the Vietnam War, in which he was a participant and recipient of the Army's Purple Heart, a look at the future of humanity and a romp through futuristic military battlefields. The book is scattered, to say the least, through these three larger themes, and while the book as a whole is a pretty strong one, reading it brought up some larger issues that I have with the whole of the military science fiction subgenre.

Branching off from the 1980s, humanity has taken to the stars fairly early in its history, travelling the galaxy via collapstars, which fires off a ship around the galaxy. During the course of humanity's exploration, they come into contact with a race of aliens known as the Taurans, and inevitably, war breaks out. The story's protagonist, William Mandella, is conscripted into the military, where he's trained and sent off to the distant front lines to fight, eventually becoming part of the first engagement against the Taurans. With that battle completed, he is shipped home, along with his lover, Marygay Potter, to an Earth that they hardly recognize. After a short period of time, they leave again, rejoin the military and rejoin the fight. Over the next several hundred years (only a couple for them, subjectively), they are retrained, and eventually separated, before one last battle brings Mandella back home, where he is eventually reunited with Marygay.

The book is ultimately lackluster as a military science fiction novel: the action scenes are nothing new, and anyone reading Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers or John Scalzi's Old Man's War will recognize the basics when it comes to this sort of novel - there are powered suits, the requisite training portion and rise of the protagonist, not to mention the action. Taken at face value, it's a bit of a miss for me. The biggest saving grace is Haldeman's conceptualization of space warfare, where tactics take days, weeks, even months to carry out, over hundreds of millions of kilometers. This gives the book a bit of a realistic edge that does make it stand apart from other military Science Fiction novels, something that I greatly appreciated.

However, where the book succeeds the most is in Haldeman's look to the future. As Mandela lives out his life through the military actions that he takes, long stretches of his life are relatively slowed down while travelling through space, allowing for jumps in time as he comes back into contact with Earth and sees just how society has changed over time. Upon his first return, humanity has united on Earth, under a largely repressive, Children of Men style world where human civilization has faced enormous hardship under the interstellar war. Leaving the world as it has changed too much for his liking, William and Marygay return to space, to find several major changes as they continue to jump around space. Eventually, the world as they know it has changed completely - humanity has gone from a recognizable society to one where homosexuality is the norm (as a form of population control) to a world where humanity has essentially merged into one asexual entity, with each generation cloned from the last. Elements of this remind me heavily of another book that I've been recently reading, Olaf Stapledon's The First and Last Men, published in the 1930s, and dealing with much the same thing: looking at how humanity as a species and culture will change in the future. Mandela's vantage point in the military is an interesting story element that allows Haldeman to not only tell an interesting story, but present a compelling future for humanity. Another book that I read last year, George Friedman's The Next 100 Years, noted that society and cultural norms can change vastly over even the period of just one hundred years, and to an extent, that lends Haldeman's and Stapleton's ideas some reality: what will happen to humanity over the next thousand years, with technological and societal advances altering what is normal? It is here that The Forever War is especially interesting.

Another major element of The Forever War is Haldeman's pointed look at the Vietnam War, no doubt inspired by his own experiences with the US Army. The book is considered a reaction to Starship Troopers, in that it takes a largely anti-military stance throughout most of the book. Mandella is a reluctant soldier, at best, often delegating his responsibilities away to subordinates and avoiding killing when he can help it. But throughout the book, there are examples of Vietnam, as humanity faces an enemy that is largely unknown, never knowing exactly what they are fighting for. More so, it is alluded to in the book that the war was fought simply because it was desired, something that was the main focus of a documentary, Why We Fight, that looked to that central theme in regards to American foreign policy. However, the core focus of this book isn't the Vietnam War itself, but the soldiers who fight there. Soldiers returning from Vietnam found themselves back home in a strange place, not as heroes of the war, but as murderers and criminals, something horribly unjust, considering that many were conscripted. This is a prime example of how science fiction should function: acting as allegory for current events, pulled out of context. Mandella returns home after hundreds and hundreds of years away from Earth; vast changes occurred while he was away.

The Vietnam comparison, however, is something that bothers me, and helps to underscore a larger issue that I have with military science fiction as a whole, something that I brought up with my review for Old Man's War: while there is a lot of discussion about the nature of war, there's very little discussion towards the institution of warfare. Tactics are almost always something out of the Second World War, with plenty of hand to hand combat scenes and all that, but there is very little on the overall impact of warfare. Sometimes, it's on the soldiers, other times, on society, but there's very little to bridge the gap. The Forever War does this in part.

Part of my issue comes from my training as a historian, and particularly, in military history. Amongst all of the theorists out there, a number of historians have come up with a number of theories on how warfare works - Clausewitz, Jomini, among others, who have both conflicting and interesting views on the nature of war. I particularly like Clausewitz's analogy that warfare is simply a duel on a larger scale, and that war is an extension of foreign policy. It makes little sense to me that humanity would simply go to war against an alien race, something fairly common in science fiction. Humanity seems to drop everything and take to the stars with lasers and rockets, but the goals of warfare are never clearly stated? Is it, as Clausewitz suggests, an effort to completely bend an enemy to one's will, something incredibly difficult when attacking someone profoundly alien and unknown to humanity, or is it something deeper, such as perceived competition for living space, ensuring that humanity will have space to grow? To date, I've never found a good military science fiction book that's really covered that territory, and at times, the genre makes me want to throw things, simply because warfare doesn't work like that.

Similarly, while powered robotic suits are very cool, the other problem that I have is tactical. Robotic powered armor laden down with guns simply doesn't make a whole lot of sense to me, especially when the authors talk much about dropping soldiers onto the planet from orbit in a glorified Omaha Beach scenario, where these soldiers are not only placed into hostile territory, but usually without support: it reminds me very much of airborne doctrine during the Second World War, where highly mobile forces were used to secure areas and wait for heavier things, such as artillery and armor to arrive. It's a good concept, to be sure, but it's deeply flawed in that these soldiers are usually out matched by the occupying force. Science Fiction takes many similar themes, but fails to follow up these sort of tactical options in any way that makes sense. Thus far, the best thing that I've seen was here, The Physics of Space Battles, which talks much about orbits and how that aspect would work, on a tactical level. Haldeman gets some points for interesting scenes and more science to the battles than most, but still misses part of the mark.

Part of that reason might be that The Forever War isn't really a military science fiction book, despite some of the content. In that instance, the book works wonderfully, hitting all of the marks of a fantastic science fiction novel. Still, I enjoy a good romp with powered armor and shooting, so it works fairly well when it comes to that, but not as much as I'd like.

When I was in High School, I devoured Ender's Game and Starship Troopers, but it wasn't until I'd left graduate school that someone forced me to read The Forever War. When I did, I

When I was in High School, I devoured Ender's Game and Starship Troopers, but it wasn't until I'd left graduate school that someone forced me to read The Forever War. When I did, I

Tomorrow, John Joseph Adam's latest original anthology, Armored, hits stores. I'm pretty excited for this one, because I've read most of it already. Last year, the book was announced, and I got to help out a bit with some of the behind the scenes work in getting the book up and running: slush reading, some recommendations, and thoughts that I had about the stories that I read.

Tomorrow, John Joseph Adam's latest original anthology, Armored, hits stores. I'm pretty excited for this one, because I've read most of it already. Last year, the book was announced, and I got to help out a bit with some of the behind the scenes work in getting the book up and running: slush reading, some recommendations, and thoughts that I had about the stories that I read. The point that comes the most readily to mind when thinking about Ender's Game is the way military strategy is conceived of and executed. Of all of the Military Science Fiction novels that I've read, there are very few that really capture one of the major elements of combat, the strategic and leadership components that make a battlefield commander effective against an enemy force.

The point that comes the most readily to mind when thinking about Ender's Game is the way military strategy is conceived of and executed. Of all of the Military Science Fiction novels that I've read, there are very few that really capture one of the major elements of combat, the strategic and leadership components that make a battlefield commander effective against an enemy force. Nine or so years ago, I worked as a counselor at a summer camp in northern Vermont, a job that involved long hours working with kids nearly twenty-four hours a day. Counselors worked under the supervision of village directors, who had their own cabins, and generally allowed use of the building as a break room for those couple of hours that we had off when we weren’t teaching classes or had some down time with no responsibilities. Where I had been introduced to Dungeons and Dragons while a counselor in training in 2000, I was introduced to Bungie’s Halo: Combat Evolved, something that suddenly appeared in each of the four villages, and something that everyone seemed to play.

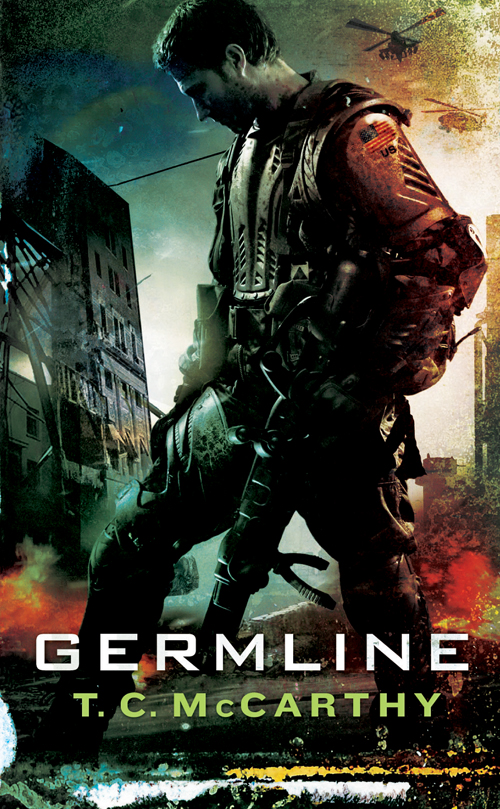

Nine or so years ago, I worked as a counselor at a summer camp in northern Vermont, a job that involved long hours working with kids nearly twenty-four hours a day. Counselors worked under the supervision of village directors, who had their own cabins, and generally allowed use of the building as a break room for those couple of hours that we had off when we weren’t teaching classes or had some down time with no responsibilities. Where I had been introduced to Dungeons and Dragons while a counselor in training in 2000, I was introduced to Bungie’s Halo: Combat Evolved, something that suddenly appeared in each of the four villages, and something that everyone seemed to play. A common talking point that I’ve found when it comes to military science fiction is that it's not a game. War is more than a bunch of soldiers dressed up in powered armor, shooting at aliens or their enemies, and telling a good story set against a backdrop of an epic war that pits the good guys against the bad guys. More than its surrounding features, military science fiction is a way to look at the present day. Germline, by TC McCarthy is a book that really gets the complexity, danger and horrors of warfare. It's the shock to the system that the first World War was to the civilized world, where they saw, first-hand, that war is a cruel and unforgiving institution.

A common talking point that I’ve found when it comes to military science fiction is that it's not a game. War is more than a bunch of soldiers dressed up in powered armor, shooting at aliens or their enemies, and telling a good story set against a backdrop of an epic war that pits the good guys against the bad guys. More than its surrounding features, military science fiction is a way to look at the present day. Germline, by TC McCarthy is a book that really gets the complexity, danger and horrors of warfare. It's the shock to the system that the first World War was to the civilized world, where they saw, first-hand, that war is a cruel and unforgiving institution.