Everybody’s Going to the Moonbase

/ During a campaign stop in Florida in advance of the next Republican Primary, former speaker of the house Newt Gingrich promised the moon and the stars to Florida voters: "By the end of my second term, we will have the first permanent base on the moon, and it will be American."

During a campaign stop in Florida in advance of the next Republican Primary, former speaker of the house Newt Gingrich promised the moon and the stars to Florida voters: "By the end of my second term, we will have the first permanent base on the moon, and it will be American."

It's one of the few things that I've heard from Gingrich that I've liked: returning to space with the full backing of the United States government. With a real perception that the United States has begun to fall behind other countries when it comes to programs in space and with NASA facing budget cut backs and the loss of its most visible program, the Space Shuttle, it’s a nice thing to hear, especially for those who focus on US efforts in space. However, it’s also an empty promise on Gingrich’s part, designed simply to gain traction against his rival, Mitt Romney in advance of the debates.

The Florida ‘Space Coast’ relies much on the infrastructure that's been built up around NASA's launch facilities: the demise of the Apollo Program in the 1970s led to massive layoffs, while the more recent Space Shuttle cancellation has led to further reductions of demand for the highly skilled work force that the industry requires. It's easy to see why Gingrich would propose such a program in Florida: it means hundreds of thousands of new, high paying jobs. At the same time however, it means a complete reversal of personal philosophy, because it would require a massive government program and spending to rebuild the space program to the point where not only reaching the moon, but also establishing a logistical system to support it, would be the first steps. Once established, it's an expensive, ongoing effort to build, maintain, supply and staff a permanent habitation on the lunar surface.

United States space programs have an odd effect on domestic politics: Republicans, traditionally the supporters of limited or restrained government, support such programs: it's heavily tied to defense and national pride, while Democrats typically see the money that's going off-planet as something that can be used to help solve the numerous problems back on the ground. Gingrich, attempting to fulfill his own fantasies, would never get far with a right-of-center government that is looking to bring down government spending (presumably), while the money that is left over would be fought over by those who's programs are being slashed.

The drive to go to the moon wasn't a whim of the U.S. public: it was the result of a carefully crafted argument made for its existence: national security. The development of rockets that could take people and equipment up to space were in place to support Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, as a check against Soviet power growing in Europe and elsewhere in the world. A highly public and dramatic example of the progression of U.S. technology, the existence of a space program capable of reaching the moon was a powerful indication of what the country could do. Certainly, if NASA could send people to walk around on the moon, the Soviet Union was well within reach of the U.S. Strategic Air Command and its nuclear arsenal.

NASA's budget began at a relatively small amount in 1958: $89 million, $488 million as of 2007. This would steadily grow from .1% of the US budget to 2.29% of the federal budget following President Kennedy's speech at Rice University in 1962. The budget for NASA would then double to 4.41% in 1966, during the height of the Gemini and Apollo programs, and would steadily decline. By the time we landed on the moon in 1969, it was back down to 2.31%, or $4.2 billion dollars. ($21.1 billion today). As of 2007, NASA's budget was around $17 billion dollars, but at the equivalent of .6% of the entire US budget. With the entire economic health of the United States in question, it's a program that's largely seen as non-essential and expendable when it comes time to tighten the belt. To reach the moon, NASA would likely have to return to spending levels seen in the 1960s: twice the budget that's been on the books, for sustained periods of time, and on top of that, maintain public engagement for the same amount of time.

Returning to the moon isn't something that can be picked up after forty years, requiring an entirely different mindset and mission stance than the low-earth orbit work that's been done since the early 1980s. New rockets would need to be constructed, and an entirely new logistical support system would need to exist to support such a mission.

This is all before one asks the next question: why return to the Moon and why set up a permanent base on its surface? The original lunar missions were exploratory in nature, and the first people over the finish line in an international race. The Cold War is long since over, the United States has proved that they could reach the moon, and the American public returned to their lives back on Earth. A self-sustaining moon program simply cannot exist for the sake of its own existence, and cannot exist as a show to the rest of the world. A graduated, strategic plan for going to the Moon and beyond, for a concrete, supportable purpose is the only way that the United States will work to go beyond Low Earth Orbit.

There are potential resources in the skies above Earth. Asteroids contain a number of metals, and there's quite a bit of scientific knowledge to be gained, but somehow, I don't think that Gingrich had anything in mind other than restoring the glory days of the United States.

Gingrich isn't going to go far with this plan: already, Romney has slammed him for his plan: "That's the kind of thing that's gotten this country into trouble in the first place." I disagree with Romney's assertion: going to the Moon brought about quite a lot of technology and a sense of security. As Craig Nelson noted in his 2009 book, Rocket Men: The Epic Story of the First Men On The Moon, going to the moon was one of the great endeavors that makes the country worth defending. But, there's a lot of competition for that sort of thing, and I don't foresee a serious, government-backed program coming to fruition in the near future during the current economic climate.

Romney's words indicate that a space program under his administration would fare worse, and of the two, Gingrich's attitude is the best of the group - if he was serious about it. Of course, if he was serious about it, he'd have serious questions about his self-proclaimed description as a 'Reagan-style conservative'. Either way, the Obama administration's move to bring about a space industry using private enterprise seems to be to be the best way to foster the growth of a sustainable American presence in space, something that seems like it would be far more in line with what a Republican administration would back.

Returning to space should be a priority for the country: it’s a means to accomplish great things, from walking on another planet’s surface, to discover incredible things, and to advance the human race far beyond its imagination. At the same time, it’s a way to ensure an industry that is advanced and highly skilled, which is something that will keep us in space even longer. Because of that, I don't believe that it should be a political football, simply to score a couple of percentage points.

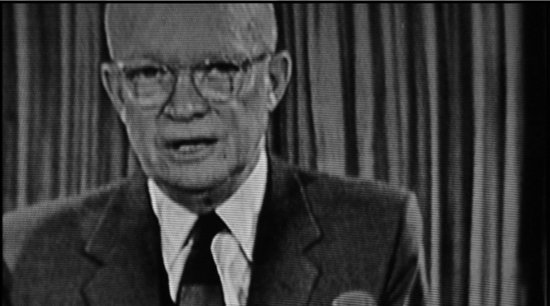

This week marks the 50th anniversary of two important speeches in recent United States history, President John F. Kennedy's Inauguration Speech on January 20th, 1961, and President Dwight Eisenhower's final farewell to the nation on January 17th. One reflects the honest assessment of a president unchained and free to speak, the other constrained by politics and optimism. In a large way, each speech speaks to one's supporters, but also to the base elements that helps define the right and the left in the United States, and in a very real way, provide an excellent primer on not only the environment of the Cold War, but also some of the roots of political speculative fiction and ideas that helped to define an generation and an art that they consumed.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of two important speeches in recent United States history, President John F. Kennedy's Inauguration Speech on January 20th, 1961, and President Dwight Eisenhower's final farewell to the nation on January 17th. One reflects the honest assessment of a president unchained and free to speak, the other constrained by politics and optimism. In a large way, each speech speaks to one's supporters, but also to the base elements that helps define the right and the left in the United States, and in a very real way, provide an excellent primer on not only the environment of the Cold War, but also some of the roots of political speculative fiction and ideas that helped to define an generation and an art that they consumed.

I'm not voting for Brian Dubie today. I can't say that I'm terribly enthused for voting for his opponent, Peter Shumlin, because the prospect of a unified House, Senate and Governor in the state also isn't all that terribly appealing to me. However, that fear isn't outweighed by the fear of not a Republican in the office again, but by an incompetent one.

I'm not voting for Brian Dubie today. I can't say that I'm terribly enthused for voting for his opponent, Peter Shumlin, because the prospect of a unified House, Senate and Governor in the state also isn't all that terribly appealing to me. However, that fear isn't outweighed by the fear of not a Republican in the office again, but by an incompetent one.