Silent Running

/

As I've been working my way through old science fiction films from the earlier days of Science Fiction films, I've finally been able to knock another film off the list: Silent Running. A science fiction film that's been cited as inspiration for of some of my favorite recent science fiction films, such as Moon, Sunshine and Wall*E, Silent Running is a fun, but chaotic film that taps heavily into the environmental movement that was so popular during the 1960s and 1970s. The end result is a fun, entertaining flick that's become one of my favorites while I watch a number of the old classics for the first time.

Set far in the future, Earth seems to have become an environmentalist's worst nightmare: plant life has vanished from Earth, with their last remains in space, in large domed spaceships run by American Airlines, the Valley Forge. Lowell, one of four crew members, is the only one who really cares for the plants, and their significance for the human race: he hates the synthetic food that they eat, and hates his crew members for their lack of interest of passion. When the orders come along to blow up the forests and return home, he kills one of his fellow crew members and jettisons the other two into space, remaining with the last remaining dome and three small drone robots.

Alone with the robots, Lowell doesn't seem to have a plan, and sets about reprogramming the drones (which he names Huey, Dewey and Louie, after the Disney characters) and keeping the forest on his ship alive as they drift into deep space. As he does so, the forest starts to die, and his ship is rediscovered. Fearing that his disposal of his fellow crew members will be discovered, and awash in guilt over their deaths, he places the dome under the care of one of the remaining drones, and sends it off into space as he destroys the Valley Forge.

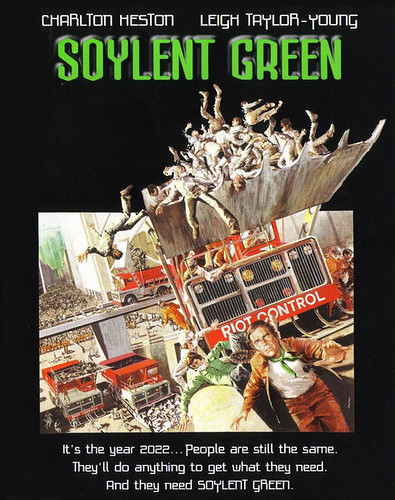

The film is a fun one - it has a tone that reminded me much of another recently viewed film, Soylent Green, which takes on some similar environmental themes for the storyline. It's a story that really holds up well today: Lowell ridicules his co-workers for the junk that they're consuming, noting that it's not real food, and it's an interesting take on how the future might turn our, forty years ago. Indeed, mass extinctions and the destruction of the environment is something that has been featured from time to time in science fiction - Soylent Green is one example, but also other recent stories such as Paolo Bacigalupi's The Windup Girl, Amaryllis by Carrie Vaughn and more recent films such as Moon. With Silent Running cited as a seminal work in the genre, it's interesting to see how forward thinking it was, with a bit of twenty-twenty hindsight.

While the film is good in concept, if fails in story, with a number of plot holes that don't make as much sense. Lowell kills his fellow crewmen in a fit of passion at the destruction of the orbital forests, and escapes through the rings of Jupiter, trying to disguise what happened as a series of malfunctions. But, for a person who seems very intent on pointing out the many things that are wrong with the world (ie, no plant life), his actions confuse the story - blowing up his crew members would be a dramatic act, an ultimate thumbing the nose at the world before taking off with the plants. At the same time, he doesn't seem to realize that plants need sunlight, and the further away one gets from the sun, the more problems a gardener will have with their garden. It's trivial, but it distracts from the story too much.

The highlight for me was not the environmental element or the visuals (which hold up well), but Drones 1, 2 and 3, Lowell's minor companions when he's on his own. Tasked with helping the crew outside, they're small, two legged robots that seem like an early influence on R2-D2 and Wall-E - and I have to say, I liked them just as much as R2, if not more - and after Lowell is injured, he reprograms each to operate on him and perform other tasks, such as playing poker. They're handled masterfully, with minimal voices and subtle movement that conveys that their emotions and apprehension, especially when poor Louie gets blown off the ship, and after Huey is damaged. I'm a little surprised that they don't get as much attention as other robots.

At the end of the day, it's easy to see why Silent Running has provided a bit of inspiration for a number of films: it's a scary film that has some major elements of truth to it: pre-packaged, synthetic food, the loss of life and habitat on the planet, and an apathetic, uninterested population that simply can't bring themselves to care about the consequences of their actions. It's a scary future, one that still could very well happen within our lifetimes.