The Lifecycle of Software Objects

/ Ted Chiang's longest work to date, The Lifecycle of Software Objects, is a fascinating story that takes a bit of a new look at how an artificial intelligence might develop. The story is understated, quiet and humble, but is exciting and touching at the same time. This was a story that I absolutely devoured in a single sitting that stretched late into the night, something that rarely happens with any story.

Ted Chiang's longest work to date, The Lifecycle of Software Objects, is a fascinating story that takes a bit of a new look at how an artificial intelligence might develop. The story is understated, quiet and humble, but is exciting and touching at the same time. This was a story that I absolutely devoured in a single sitting that stretched late into the night, something that rarely happens with any story.

The book's description includes a quote from Alan Turing that helps to set this story apart from other robot stories:

“Many people think that a very abstract activity, like the playing of chess, would be best. It can also be maintained that it is best to provide the machine with the best sense organs that money can buy, and then teach it to understand and speak English. This process could follow the normal teaching of a child. Things would be pointed out and named, etc. Again I do not know what the right answer is, but I think both approaches should be tried.”

The story follows Ana Alvarado and Derek Brooks as their own lives intertwines over the course of a decade. Software AI has been achieved, and is a growing industry at the start of the novella, one that changes as the story progresses. Fans of stories such as I, Robot or other reads about robotics will find this to be a vastly different type of story, and for that reason, it's very refreshing. Working to create Digients, a sort of artificial intelligence profile or avatar online, we see the introduction of Jax, Marco and Polo, who essentially grow up under the care of Ana and Derek.

Fiction is a product of our own lives and surroundings. Lifecycles is a good example of how Chiang was able to take a very old story type (Man creating life himself) and create something that feels new and fresh. Very often, our perceptions of robotics are shaped by dramatic presentations such as The Terminator, or The Matrix, stories that predict that the rise of a robotic race will automatically deduce that the human race will be pegged for extinction. Similarly, it’s also assumed that a comprehensive knowledge and sheer logical reasoning will prove to be a superior mind.

Chiang takes on the other side suggested by Turing in his approach to the development of an artificial intelligence, which strikes me as a far more realistic method for developing a viable computer intelligence: you make them grow up. This happens over the decade that the story takes place, but it’s far more complicated than that. In other stories, there’s never really a reason for creating a robot, or at the very least, there’s no reason given for developing a new mind. Here, it’s very much the same thing, but the reasons are stark: it’s a business, and there’s little demand for highly realistic artificial avatars that talk back or cause problems as they’re developing.

The important thing here is that there are some major philosophical issues at the heart of any sort of AI, especially when one is assuming that it will be a being along the same lines of a human: can they be purpose driven, or is there any intent to their design? Religious arguments aside, I don’t see any particular purpose to human beings, just a happy accident of chemistry and circumstances at the right time billions of years ago. So to, would a machine guided by rigid logical programming be the same thing? I think not, although the appearance could be replicated somewhat with fast programming.

Intelligence is also complicated: it’s not just that a robot would have to have 700 million languages at its disposal, or whatever actions pre-programmed into it: any such being really isn’t truly free as people seem to be. Rather, complicated intelligence (and this is from my own limited understanding) comes more with the ability to draw connections between different, unrelated things. Driving along one route, I try to infer what lies between another road that’s running parallel to me, based on what I can see in between the two locations. My dog sees my sister and realizes that not only is she outside, but that if she runs to the window, she’ll see her as she runs down into the yard. These types of responses aren’t ones that I can’t see being rigidly programmed into a computer, but are things that will learned from experience.

Interestingly, the book has far more in common with another, slightly lesser known story from Isaac Asimov (and film adaptation), The Bicentennial Man, which sees a robot learn to become a human, going to the extreme and replacing metal for flesh. I greatly enjoyed the movie (I’ve never understood the hate that it seems to elicit), and The Lifecycle of Software Objects takes some similar lines of reasoning and does them in a far better fashion.

Set amongst a sort of tech boom that would be familiar to anyone who used the internet since the 1990s, companies come and go, but the people remain, and find their own way through life. In a large way, the cover is exceedingly deceptive here, because this isn’t a story about robots, it’s a story about people who deal with robots, and one another. Chiang does a marvelous job here, setting the lives of two people in a mere thirty thousand words, where things never feel like they are rushed or that anything major has been glossed over.

Where there’s the approach to growing an intelligence, there’s a lot to be said for the people on the other side of the equation. As we watch the trio of Digients grow up in their own little world (and a times, jumping into a robot body that their owners have for them), it’s apparent that they’re as much a product of their parents than their surroundings, and that frequently, their upbringing has as much an impact on themselves as it does their caretakers. What I found most fascinating is that this isn’t really a story about robots at all: they’re central to the plot, but the real point here is in the long relationship between Ana and Derek, and how two people who are so similar can be so far apart and estranged from one another. It’s a love story in its own right, between the two humans, but also for a parent for their creation. In doing so, Chiang presents an interesting idea that robots and artificial intelligences wouldn’t be so different from us, and that the creation of an AI isn’t any different than parenting.

The story is also available online, here.

Suzanne Collins' The Hunger Games one of the latest young adult novels that's made a huge splash. The book's trilogy has recently finished up with Mockingjay, and a movie is currently in the works. Young adult fiction is experiencing a boom right now, with a lot of attention paid towards the genre since Harry Potter reinvigorated things over the last ten years. Even more for the books, a number of the recent hits steer very closely towards the

Suzanne Collins' The Hunger Games one of the latest young adult novels that's made a huge splash. The book's trilogy has recently finished up with Mockingjay, and a movie is currently in the works. Young adult fiction is experiencing a boom right now, with a lot of attention paid towards the genre since Harry Potter reinvigorated things over the last ten years. Even more for the books, a number of the recent hits steer very closely towards the

The first part of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows opens with a bang as a wizard instructor, tortured and begging for her life drops to the table, surrounded by jeering Death Eaters as she’s killed by the story’s main protagonist, Lord Voldemort. This sets the tone for the best Harry Potter film to date, one that is both a superb adaptation of the novel that it’s based upon, and a solid film in and of itself.

The first part of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows opens with a bang as a wizard instructor, tortured and begging for her life drops to the table, surrounded by jeering Death Eaters as she’s killed by the story’s main protagonist, Lord Voldemort. This sets the tone for the best Harry Potter film to date, one that is both a superb adaptation of the novel that it’s based upon, and a solid film in and of itself. A recent book caught my eyes in the bookstore the other day: Jon Armstrong's second novel, Yarn, with a gorgeous cover and an interesting looking storyline. In the midst of deciding which book to get, two others won out, and it was returned to the shelf. Followup research showed that I should have gone for it, and further searches in nearby stores came up empty.

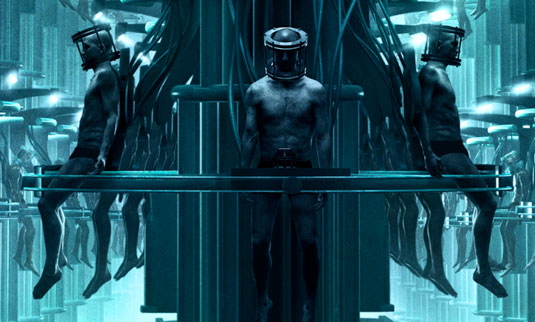

A recent book caught my eyes in the bookstore the other day: Jon Armstrong's second novel, Yarn, with a gorgeous cover and an interesting looking storyline. In the midst of deciding which book to get, two others won out, and it was returned to the shelf. Followup research showed that I should have gone for it, and further searches in nearby stores came up empty. I first watched the original Tron earlier this year based on several recommendations from friends, and was really hooked on the film. The 1982 film was one that was a neat balance between advanced effects (now very, very dated), action and a decent storyline that had a lot of potential. When the first promotional clips were released of the new Tron, it looked like it would be an interesting update of the franchise. Tron: Legacy is a fun science fiction film, and while it has its shortcomings in the plot, the visuals and excellent score make up for it.

I first watched the original Tron earlier this year based on several recommendations from friends, and was really hooked on the film. The 1982 film was one that was a neat balance between advanced effects (now very, very dated), action and a decent storyline that had a lot of potential. When the first promotional clips were released of the new Tron, it looked like it would be an interesting update of the franchise. Tron: Legacy is a fun science fiction film, and while it has its shortcomings in the plot, the visuals and excellent score make up for it. A man wakes up to discover that he's sprouted horns on his head overnight. Joe Hill's latest book, Horns, starts off with a simple premise, one that unfolds into a wonderfully complicated and minimal story of murder, revenge and the inherent darkness that exists within people. At the same time, Hill brings out a deeply philosophical and intriguing look at faith and Christian allegory.

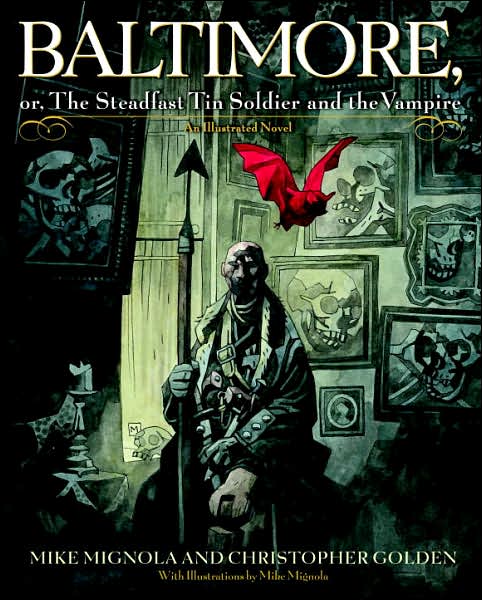

A man wakes up to discover that he's sprouted horns on his head overnight. Joe Hill's latest book, Horns, starts off with a simple premise, one that unfolds into a wonderfully complicated and minimal story of murder, revenge and the inherent darkness that exists within people. At the same time, Hill brings out a deeply philosophical and intriguing look at faith and Christian allegory. As the publishing industry has jumped wholeheartedly into the emotional Vampire trend that's seen the release of the Twilight novels, it's nice to come across a book that was published during this that really brings the horror back to the style of story. Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, by Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola is an engrossing read that both deals with vampires, and brings in a proper horror feeling to the story.

As the publishing industry has jumped wholeheartedly into the emotional Vampire trend that's seen the release of the Twilight novels, it's nice to come across a book that was published during this that really brings the horror back to the style of story. Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, by Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola is an engrossing read that both deals with vampires, and brings in a proper horror feeling to the story.

"...and then what happened?"

"...and then what happened?"