Pattern Recognition, by William Gibson

/

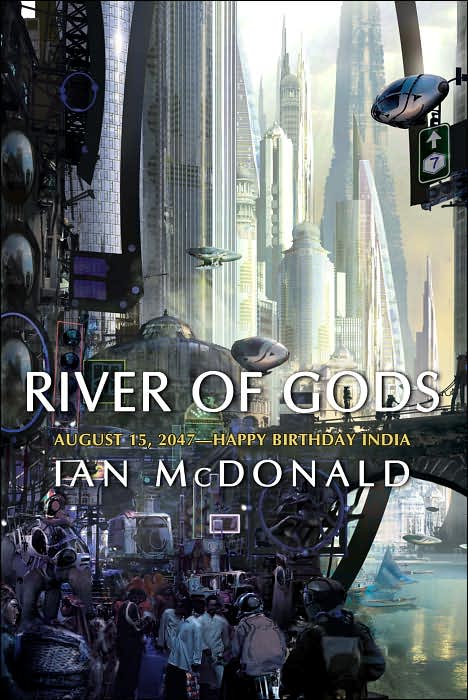

After reading Ian McDonald's River of Gods recently, I was compelled to read another science fiction novel that took place around the planet, interacting with a number of other cultures. As William Gibson's latest novel, and the last of his 'Bigend' trilogy, Zero History was recently released, I picked up the first of the series, Pattern Recognition, published in 2003. I've had the book for a number of years, but had never picked it up, or even cracked it open. My first surprise, upon doing so, was to discover that the book had been signed by Mr. Gibson.

Pattern Recognition, from an author that helped define the notion (and term) cyberspace, as well as much of the cyberpunk genre, might seem as a sort of step back. The book takes place in contemporary times, in a post-9/11 setting, in England, Japan and Russia. Media consultant Cayce Pollard is hired by a company, Blue Ant, who is redesigning a logo for a Tokyo firm. Pollard, who has an adverse reaction to logos and marketing, and a curiosity with a series of videos that have surfaced on the internet, is hired by Blue Ant founder Hubertus Bigend, who wants her to find the maker of the clips, because of the potential gain that can be achieved by learning everything about them, and why they attract so much attention. This job is one that takes her across the world, from London to Tokyo to uncover a code that would help connect the videos to a firm in the United States, and to Russia as more leads come about. Her trip around the planet is one of discovery, as she moves from world to world following information.

While the book is set in contemporary times, it fits well with Gibson's notion that science fiction doesn't have to be part of the future. Instead, this book does what the best science fiction stories do: amidst the science fictional elements that surround the story, there is a central element that defines the book. In this case, this book is about networking, and the ability of technology to bring a diverse set of people together. In 2003, this stage of the internet hadn't quite happened yet: blogging was the big thing, and Facebook was still a year away, twitter three. Pollard's quest? To find what's arguably a viral video. In a large way, Gibson has recognized the rise of social media before it happened.

While the predictions of Pattern Recognition aren't quite as revolutionary as Gibson's were with Neuromancer, this book is far more relatable, relevant, and understands the heart of the internet. The story contains very few speculative elements: Pollard's allergy to advertising (in some cases) and some of the technological elements that are at this point outdated. Author Dennis Danvers noted it best in his review:

Science fiction, in effect, has become a narrative strategy, a way of approaching story, in which not only characters must be invented, but the world and its ways as well, without resorting to magic or the supernatural, where the fantasy folks work.

In a large way, Gibson has demonstrated that he's very good at figuring out how people will use various technologies, and in a way, the gap between Neuromancer and Pattern Recognition (and presumably, its sequels, Spook Country and Zero History.) isn't as far apart as when it first meets the eye. Pattern Recognition illustrates a reality that is cold, separated from humanity while being connected at almost all times through the internet. Gibson makes the point that the future isn't far away, it's right now, this very moment.

Indeed, Gibson is probably one of the few science fiction authors to see his works come to life - not only in the details as to what he's written, but in how the future has been realized. It's a bit of a given point, seeing how the book has been set, but between 2003 (when I entered college) and the present day (out of school and working for several years) the world has changed immensely, not just in the speeds and the availability of communications, but in how people understand and utilize the internet. This seems to have been anticipated, and while the real world is already leaving this story behind, it's clear that there are some lessons here that can be learned: we're all connected.

As a story, the execution leaves a book that makes me feel much like Chris Kelvin from Solaris: isolated, cold, somewhat depressed, and Gibson writes Pollard’s character as a fairly empty person, someone who is socially isolated, but at the same time connected to those people whom she shares mutual interests with. Pollard’s journey across the planet in search of a revolutionary form of marketing is an interesting one across a number of countries and subcultures that could only exist in the internet age. At journey’s end in Moscow, Pollard comes to meet the maker of the clips, and an interesting story of commercial viability vs. artistic creativity is brought full circle.

While it’s not as groundbreaking, Pattern Recognition succeeds by using science fiction as a mirror, demonstrating not only that we live in a futuristic world, it’s one that we’re only now fully realizing as we live it.