This was a great year for reading. A lot of excellent fiction was released, and I felt like I got a lot of good out of my year from the books that I picked up. Here's what I read.

1- A Fiery Peace in a Cold War, Neil Sheehan (1-14)

This was a fantastic history on the Cold War, one that I wish I'd come across while I was working on my project. I've revisited it a couple of times since the start of the year for other projects.

2 - The Forever War, Joe Halderman (1-28)

This was a book that had come highly recommended for years, and I really enjoyed how it was more about people than guns and brawn.

3 - The Monuments Men, Robert Edsel (2-8)

During the Second World War, a team of specialists were dispatched around Europe to save art from the effects of war, the focus of this book. It's a little uneven, but tells an astonishing story.

4 - We, John Dickinson (2-19)

This was a crappy book. Amateurish and poorly written.

5 - Coraline, Neil Gaiman (2-24)

I watched the movie around the same time, and I've long like Gaiman's works. This was an excellent YA novel.

6 - Your Hate Mail Will Be Graded, John Scalzi (3-4)

Scalzi's Whatever blog is always an entertaining read, and this collection takes some of the better entries into a book of short essays. Thought-provoking, interesting and well worth reading.

7 - Shadowline, Glenn Cook (3-6)

With all of my complaints about military science fiction not being all that accurate or conceived of, Shadowline is one of the few books that have made me eat my words - there's some well conceived ideas here, and this reprint from Night Shade Books was a fun read.

8 - The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, N.K. Jeminsin (3-19)

N.K. Jemisin's first novel came with a lot of buzz, and I really enjoyed reading it from start to finish. It's a very different blend of fantasy than I've ever read.

9 - Spellwright, Blake Charlton (3-29)

Spellwright was probably one of my favorite reads of the year - it was fast, entertaining and thoughtful - a good fantasy debut, and I'm already eager for the sequel.

10 - The Gaslight Dogs, Karin Lowachee (4-21).

Karin Lowachee's Warchild was a favorite book from my high school years, and I was delighted to see her back after a long absence. This steampunk novel is an unconventional one, and a good example for the rest of the genre to follow.

11 - The Mirrored Heavens, David J. Williams (5-17)

David J. Williams contacted me after I wrote an article on military science fiction, and I went through his first book with vigor - it's a fast-paced, interesting take on military SF and a bit of Cyberpunk.

12 - Third Class Superhero, Charles Yu (5-28)

Charles Yu distinguished himself as a talented writer with his short fiction, and his recently released collection shows off some great stories.

13 - Ship Breaker, Paolo Bacigalupi (6-1)

Bacigalupi goes to Young Adult fiction with Ship Breaker, an excellent read set in a post-oil world. He gets a lot of things right with this: the surroundings and trappings of the world aren't always important, but the characters and their struggles are timeless.

14 - Boneshaker, Cherie Priest (6-8)

This much-hyped book was one that I avoided for a while, but I blew through it after I picked it up. It's a fun, exciting read in the quintessential steampunk world that Priest has put together. I love this alternate Seattle.

15 - To A God Unknown, John Steinbeck (7-15)

Steinbeck's book is a dense one that took me a while to read through while I was reading several books at one. It's an interesting take on biblical themes and on faith itself.

16 - American Gods, Neil Gaiman (7-25)

This was a book that was a pick for the 1b1t movement on twitter (something I hope returns), and I was happy for the excuse to re-read this fantastic novel. It's one of my favorite books of all time, and this time around, it was fantastic to have that reaffirmed.

17 - The Burning Skies, David J Williams (7-25)

The followup to the Mirrored Heavens, this book took me a while to get through because it was dense and intense. A decent read, but it proved to be a bit of a chore to get through.

18 - How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, Charles Yu (7-30)

This was probably one of the best science fiction books that I've read in a long time. It's brilliant, well written, interesting and part of the story itself. It's an outstanding take on time travel as well.

19 - River Of Gods, Ian McDonald (9-2)

I've long heard of Ian McDonald, but I hadn't picked up any of his stories before now. His take on a future India is a fantastic one, and can't wait for more of his stories. River of Gods broke the mold when it comes to western science fiction: the future will be for everyone.

20 - Clementine, Cherie Priest (9-3)

This short novella was a bit too compact for the story that it contained, but it demonstrated that The Clockwork Century is something that can easily extend beyond Boneshaker.

21 - Pattern Recognition (9-11)

William Gibson's book from a couple of years ago, taking science fiction to the present day in this thriller. It's a fun read, and I've already got the sequels waiting for me.

22 - New Model Army, Adam Roberts (9-22)

This military science fiction book had an interesting premise: what happens when crowdsourcing and wikiculture comes to warfare. The book is a little blunt at points, but it's more thought provoking than I thought it would be.

23 - Stories, edited by Neil Gaiman (9-26)

An excellent anthology of short stories from all over the speculative fiction genre. There's some real gems in there.

24 - Andvari's Ring, Arthur Peterson (9-26)

A translation of norse epic poetry from the early 1900s, this book looks and feels like a book should, and is one of those bookstore discoveries that I love. This was a fun book that has roots for a number of other stories in it.

25 - The City and The City, China Miéville (9-30)

One of my absolute favorite stories of the year came with this book, my first introduction to Mieville. This murder mystery set against a fantastic background has some great implications that go with the story.

26 - Pump Six and Other Stories, Paolo Bacigaulupi (10-22)

A paperback version of Bacigalupi's stories was released towards the end of the year, and I have to say, it's one of the more disturbing reads of the year, but also one of the most excellent.

27 - The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Washington Irving (10-31)

I did a little reading on Washington Irving and found an e-book of this while I was going through a bit of a fascination on the gothic / horror genre. This book does it well. Hopefully, I'll be able to do a bit more research on the author and his fiction this year.

28 - The Walking Dead, Robert Kirkman (11-8)

The television show was an interesting one, and I finally was able to catch up on the comic that started it. They're very close to start, but that changes after a couple of episodes. Some of the characters were spot on.

29 - Baltimore, or,The Steadfast Tin Soldier, Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola. (11-8)

This was a fun read: Mike Mignola and Christopher Golden both have some great storytelling abilities when it comes to horror fiction, and their take on vampires is an excellent one.

30 - Dreadnought, Cherie Priest (11-10)

Cherie Priest had a really good thing with Boneshaker, but Dreadnought was a bit of a disappointment. It didn't have the same flair or feeling that the first book did, but it did do some things that I'd wanted to see in Boneshaker. It's an interesting series, and I'll be interested to see what happens next.

31 - Lost States, Michael Trinklein (11-13)

This was a fun book that I came across in a local store on states that didn't make it. It's a fun, quick read with a number of fun stories.

32 - The Jedi Path, Daniel Wallace (11-14)

While I thought this book wasn't worth the $100 for all the frills and packaging, this is a really cool read for Star Wars fans, going into some of the history and methods of the Jedi Order.

33 - Horns, Joe Hill (11-22)

This was the other absolutely fantastic book that I read this year (reading it as an ebook and then from the regular book) from localish author Joe Hill. The story of a man who sprouts horns and a small, emotional story about his life. It's an astonishing read, and one that will hopefully be up for a couple of awards.

34 - Doom Came to Gotham, Mike Mignola (11-24)

This was a fun, alternate take on the Batman stories in a steampunk world. Batman + Mignola's art = awesome.

35 - Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, J.K. Rowling (11-28)

36 - Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, J.K. Rowling (11-29)

37 - Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, J.K. Rowling (12-1)

38 - Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, J.K. Rowling (12-3)

39 - Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, J.K. Rowling (12-12)

40 - Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince, J.K. Rowling (12-15)

41 - Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows, J.K. Rowling (12-18)

I'm not going to talk about each Potter novel in turn, but as a single, continuous story, Rowling has put together a hell of a story here. Outstanding characters and storylines, and the works as a whole are greater than the sum of their parts.

42 - The Magicians, Lev Grossman (12-27)

The logical book to read after the Harry Potter series was Lev Grossman's novel that can be described as an anti-Harry Potter. It's a fun novel the second time through, and good preparation for his followup this year.

43 - Brave New Worlds, John Joseph Adams (12-31)

The review for this book is coming shortly, but I have to say, it's one of the best anthologies that I've ever read.

On to 2011!

I have a feeling that my reading will become a little more convoluted in a bit when I have a couple of reviewer copies coming in, and with a couple of books on the docket right at the moment, with some others in the queue, I need to get my head straight.

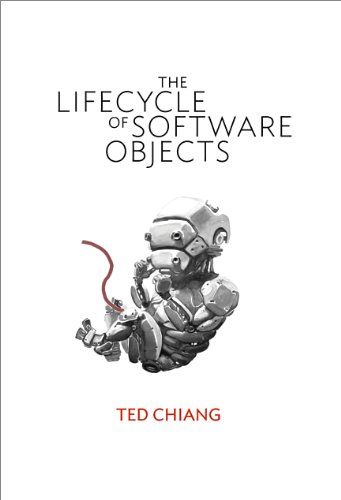

I have a feeling that my reading will become a little more convoluted in a bit when I have a couple of reviewer copies coming in, and with a couple of books on the docket right at the moment, with some others in the queue, I need to get my head straight. Ted Chiang's longest work to date, The Lifecycle of Software Objects, is a fascinating story that takes a bit of a new look at how an artificial intelligence might develop. The story is understated, quiet and humble, but is exciting and touching at the same time. This was a story that I absolutely devoured in a single sitting that stretched late into the night, something that rarely happens with any story.

Ted Chiang's longest work to date, The Lifecycle of Software Objects, is a fascinating story that takes a bit of a new look at how an artificial intelligence might develop. The story is understated, quiet and humble, but is exciting and touching at the same time. This was a story that I absolutely devoured in a single sitting that stretched late into the night, something that rarely happens with any story. Suzanne Collins' The Hunger Games one of the latest young adult novels that's made a huge splash. The book's trilogy has recently finished up with Mockingjay, and a movie is currently in the works. Young adult fiction is experiencing a boom right now, with a lot of attention paid towards the genre since Harry Potter reinvigorated things over the last ten years. Even more for the books, a number of the recent hits steer very closely towards the

Suzanne Collins' The Hunger Games one of the latest young adult novels that's made a huge splash. The book's trilogy has recently finished up with Mockingjay, and a movie is currently in the works. Young adult fiction is experiencing a boom right now, with a lot of attention paid towards the genre since Harry Potter reinvigorated things over the last ten years. Even more for the books, a number of the recent hits steer very closely towards the

Last year, I picked up Ian McDonald's fantastic science fiction novel River of Gods and loved his take on an India of the future. With his latest book, The Dervish House, McDonald relocates to Turkey of 2027. Rarely do I come across a book that absolutely floors me, and where River of Gods really impressed me, The Dervish House completely bowled me over with its interconnecting storylines, fantastic prose and wonderful characters.

Last year, I picked up Ian McDonald's fantastic science fiction novel River of Gods and loved his take on an India of the future. With his latest book, The Dervish House, McDonald relocates to Turkey of 2027. Rarely do I come across a book that absolutely floors me, and where River of Gods really impressed me, The Dervish House completely bowled me over with its interconnecting storylines, fantastic prose and wonderful characters. A recent book caught my eyes in the bookstore the other day: Jon Armstrong's second novel, Yarn, with a gorgeous cover and an interesting looking storyline. In the midst of deciding which book to get, two others won out, and it was returned to the shelf. Followup research showed that I should have gone for it, and further searches in nearby stores came up empty.

A recent book caught my eyes in the bookstore the other day: Jon Armstrong's second novel, Yarn, with a gorgeous cover and an interesting looking storyline. In the midst of deciding which book to get, two others won out, and it was returned to the shelf. Followup research showed that I should have gone for it, and further searches in nearby stores came up empty. John Joseph Adams has distinguished himself in the past with outstanding speculative fiction anthologies, from Wastelands to The Living Dead and others. His latest volume, Brave New Worlds, is perhaps one of the finest sets of short fiction that I've ever read, with a stunning table of contents and authors to tell their stories of oppression.

John Joseph Adams has distinguished himself in the past with outstanding speculative fiction anthologies, from Wastelands to The Living Dead and others. His latest volume, Brave New Worlds, is perhaps one of the finest sets of short fiction that I've ever read, with a stunning table of contents and authors to tell their stories of oppression. With the new year upon us, I've wrapped up my list of what I've read all of last year, and taken the books that I've got sitting on a shelf waiting to read for the next 365 days. I've got no illusions that I'll get through this entire list in one year - there's certainly books that I had planned to read in 2010 that I never got around to, but it's a starting point, to be sure.

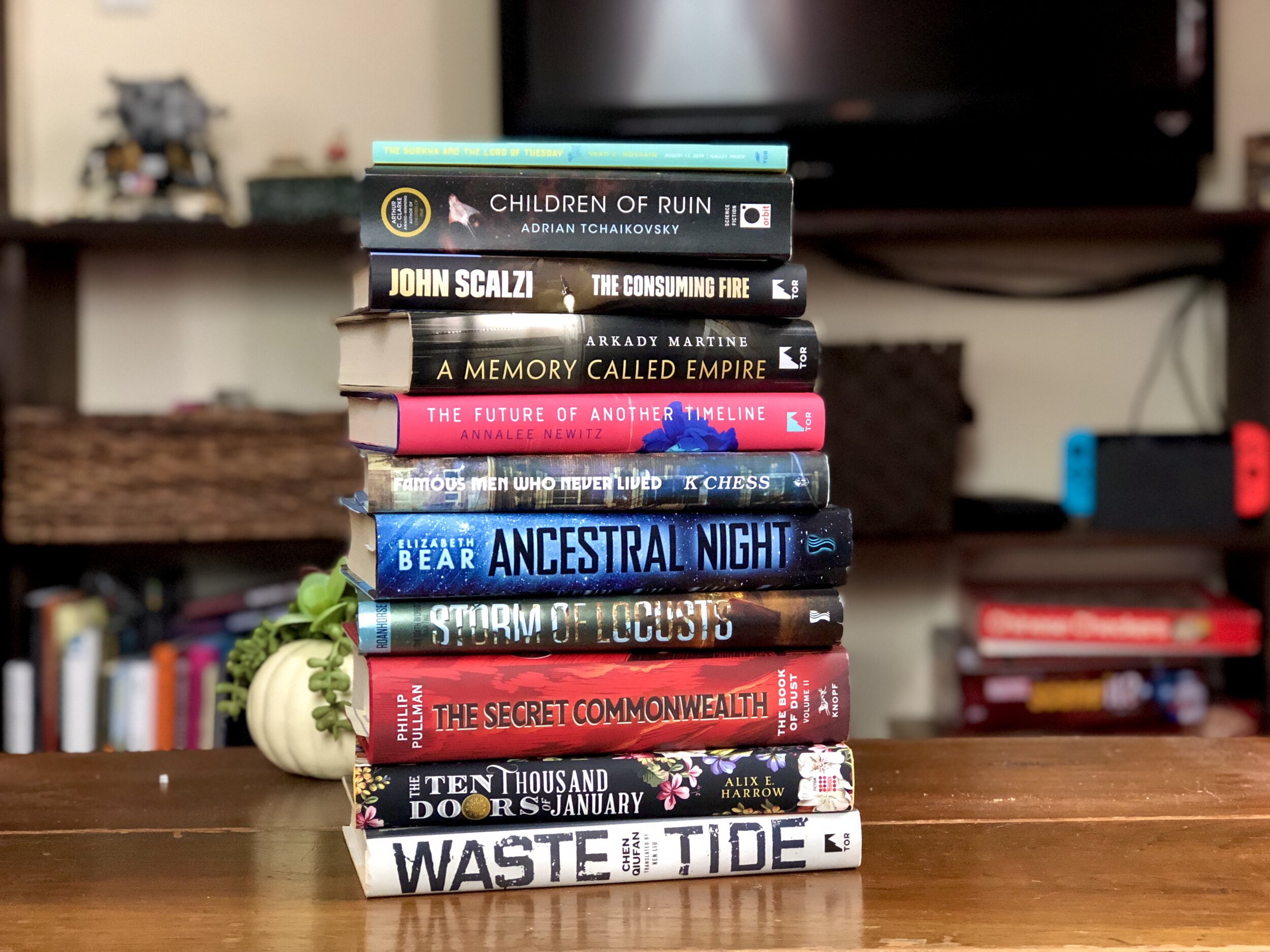

With the new year upon us, I've wrapped up my list of what I've read all of last year, and taken the books that I've got sitting on a shelf waiting to read for the next 365 days. I've got no illusions that I'll get through this entire list in one year - there's certainly books that I had planned to read in 2010 that I never got around to, but it's a starting point, to be sure.

As 2010 closes out, there's the inevitable looking forward to the new year. There's already a small, but growing list of books that are coming out that has been percolating in the back of my head. Some of these are authors that I've never read before, some are ones from familiar people, but all looked interesting to me. Here's what I've got thus far:

As 2010 closes out, there's the inevitable looking forward to the new year. There's already a small, but growing list of books that are coming out that has been percolating in the back of my head. Some of these are authors that I've never read before, some are ones from familiar people, but all looked interesting to me. Here's what I've got thus far:

A man wakes up to discover that he's sprouted horns on his head overnight. Joe Hill's latest book, Horns, starts off with a simple premise, one that unfolds into a wonderfully complicated and minimal story of murder, revenge and the inherent darkness that exists within people. At the same time, Hill brings out a deeply philosophical and intriguing look at faith and Christian allegory.

A man wakes up to discover that he's sprouted horns on his head overnight. Joe Hill's latest book, Horns, starts off with a simple premise, one that unfolds into a wonderfully complicated and minimal story of murder, revenge and the inherent darkness that exists within people. At the same time, Hill brings out a deeply philosophical and intriguing look at faith and Christian allegory. It’s hard to mention the term Steampunk without also mentioning Cherie Priest’s Clockwork Century series, an alternate history of the United States, featuring all of the bells and whistles that comes with the territory. The first novel, Boneshaker, was well received, as was the short novella, Clementine, set shortly after the events of the first book, while the latest entry in the series (there are two more planned), Dreadnought, picks up the story across the country and helps to flesh out Priest’s strange alternate world. An interesting follow-up to Boneshaker, Dreadnought never quite reaches the same heights that its predecessor reached, nor does it quite feel as unique. As such, Priest brings out new elements to the Civil War only hinted at in the previous books, and tells a fun story, one that is sure to be popular with the steampunk crowd.

It’s hard to mention the term Steampunk without also mentioning Cherie Priest’s Clockwork Century series, an alternate history of the United States, featuring all of the bells and whistles that comes with the territory. The first novel, Boneshaker, was well received, as was the short novella, Clementine, set shortly after the events of the first book, while the latest entry in the series (there are two more planned), Dreadnought, picks up the story across the country and helps to flesh out Priest’s strange alternate world. An interesting follow-up to Boneshaker, Dreadnought never quite reaches the same heights that its predecessor reached, nor does it quite feel as unique. As such, Priest brings out new elements to the Civil War only hinted at in the previous books, and tells a fun story, one that is sure to be popular with the steampunk crowd.

As the publishing industry has jumped wholeheartedly into the emotional Vampire trend that's seen the release of the Twilight novels, it's nice to come across a book that was published during this that really brings the horror back to the style of story. Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, by Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola is an engrossing read that both deals with vampires, and brings in a proper horror feeling to the story.

As the publishing industry has jumped wholeheartedly into the emotional Vampire trend that's seen the release of the Twilight novels, it's nice to come across a book that was published during this that really brings the horror back to the style of story. Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, by Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola is an engrossing read that both deals with vampires, and brings in a proper horror feeling to the story.