Survivor Song by Paul Tremblay

/Reading Paul Tremblay’s latest in the middle of a global pandemic was an interesting experience. I had to put this down more than once, because at times, it just felt too real. An aggressive form of rabies has begun to spread, infecting its victims within a matter of hours, pushing them to violently attack and bite those around them, spreading the illness even faster through the community.

As the book opens, we meet Natalie and Paul, who are attacked in their home by a neighbor. Paul is killed and Natalie is bitten. She calls her friend, Rams — Dr. Ramola Sherman — a doctor at a local hospital that’s been dealing with the influx of patients. There’s a complication: Natalie is pregnant and nearly due, and it’s a race against time and across the city to get a vaccine and bring her to safety before she gives birth.

I’ve admired Trembley’s recent novels (A Head Full of Ghosts, Disappearance at Devil’s Rock, and Cabin at the End of the World) for his take on the horrific: he has a light touch, letting the reader wonder if what the characters are experiencing is really supernatural, or just in their heads. With each book, he’s placed his own spin on established genre tropes — exorcisms, ghosts, or home invasions — and with Survivor Song, he turns his attention to zombies.

There’s been a glut of zombie stories out there in the last decade, from straight-up horror like The Walking Dead and ZNation, to the more inventive, like Santa Clarita Diet or iZombie. It’s a trope that’s been done to death (sorry), but Tremblay’s managed to put a new perspective on it, examining the crisis as a public health issue. The violent residents of Massachusetts that Rams and Natalie have to contend with aren’t the goulish undead, but are people who are desperately, fatally ill. Tremblay sprinkles in plenty of pop culture references, from The Cranberries’ ‘Zombie’ to references to the various films and shows out there, pushing back on them with a sense of realism.

The horror in Survivor Song comes with its relentless pace: the book takes place over the span of a couple of hours as Natalie begins to deteriorate, leaving messages for her as-of-yet-unborn daughter as she and Rams try and get help from one hospital after another.

The other facet of the horror comes from the obvious, mirroring the last six months that we’ve endured this pandemic. Toward the end of the novel, one particular passage jumped out at me:

“In the coming days, conditions will continue to deteriorate. Emergency services and other public safety nets will be stretched to their breaking points, exacerbated by the wily antagonists of fear, panic, misinformation; a myopic, sluggish federal bureaucracy further hamstrung by a president unwilling and woefully unequipped to make the rational, science-based decisions necessary; and exacerbated, of course, by plain old individual everyday evil.

While the book arrived in bookstores in the midst of the pandemic, Tremblay tells me that he wrote the book long before it took place. But while it makes for a hard read because of how closely elements of it have tracked with real life — lockdowns, the panic buying in stores, the sense of dread and uncertainty — the book shows that the ingredients needed for such an event were systematically laid by evil and corrupt men who peddle in misinformation, anti-science rhetoric and who are unable to confront the challenges before them. That’s the real horror, and it’s one that doesn’t require a reader to suspend their disbelief.

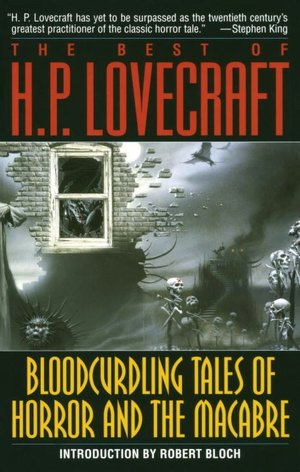

With October a traditionally - horror themed month capped with Halloween, it seemed appropriate to follow up Bram Stoker and Dracula with another notable horror author: H.P. Lovecraft. Hugely influential in the horror genre, Lovecraft is an author that I got into while in college, with a course on Gothic Literature. I've found Lovecraft's stories to be delightfully macabre, and living in Vermont, I can identify with his love of the sheer age of the location, and can see just why this corner of the country is so suited for horror fiction.

With October a traditionally - horror themed month capped with Halloween, it seemed appropriate to follow up Bram Stoker and Dracula with another notable horror author: H.P. Lovecraft. Hugely influential in the horror genre, Lovecraft is an author that I got into while in college, with a course on Gothic Literature. I've found Lovecraft's stories to be delightfully macabre, and living in Vermont, I can identify with his love of the sheer age of the location, and can see just why this corner of the country is so suited for horror fiction. A man wakes up to discover that he's sprouted horns on his head overnight. Joe Hill's latest book, Horns, starts off with a simple premise, one that unfolds into a wonderfully complicated and minimal story of murder, revenge and the inherent darkness that exists within people. At the same time, Hill brings out a deeply philosophical and intriguing look at faith and Christian allegory.

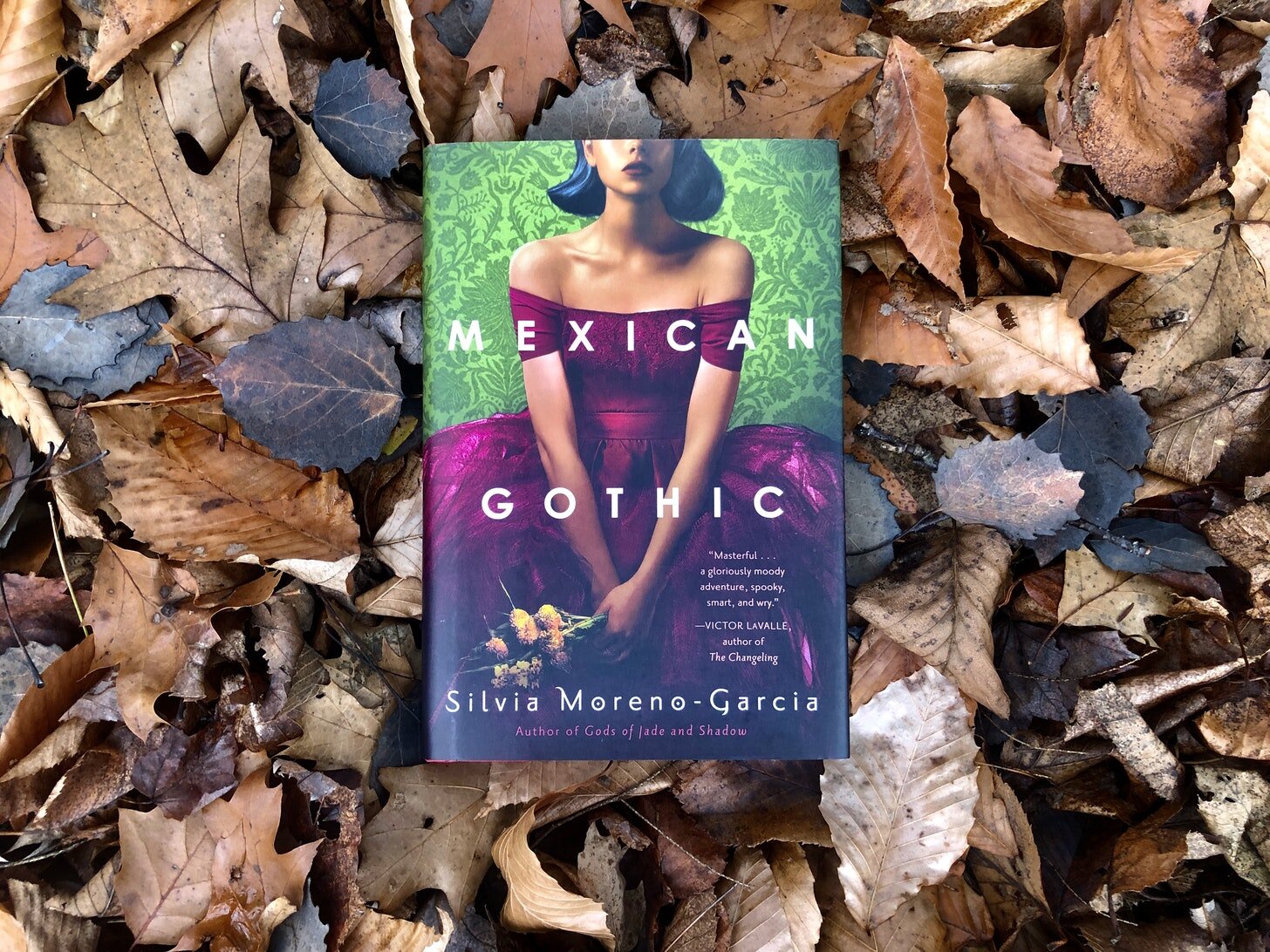

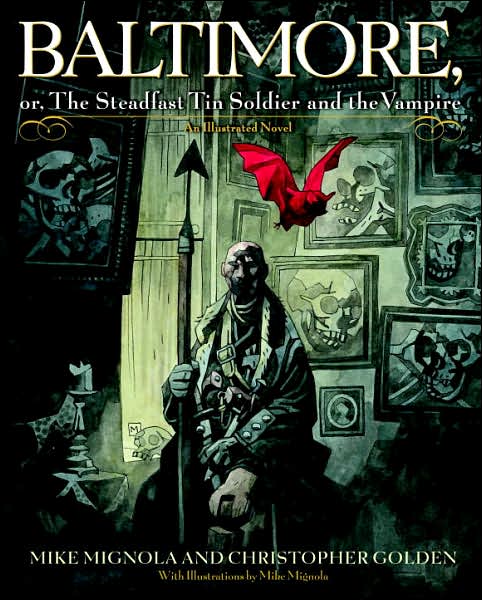

A man wakes up to discover that he's sprouted horns on his head overnight. Joe Hill's latest book, Horns, starts off with a simple premise, one that unfolds into a wonderfully complicated and minimal story of murder, revenge and the inherent darkness that exists within people. At the same time, Hill brings out a deeply philosophical and intriguing look at faith and Christian allegory. As the publishing industry has jumped wholeheartedly into the emotional Vampire trend that's seen the release of the Twilight novels, it's nice to come across a book that was published during this that really brings the horror back to the style of story. Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, by Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola is an engrossing read that both deals with vampires, and brings in a proper horror feeling to the story.

As the publishing industry has jumped wholeheartedly into the emotional Vampire trend that's seen the release of the Twilight novels, it's nice to come across a book that was published during this that really brings the horror back to the style of story. Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, by Christopher Golden and Mike Mignola is an engrossing read that both deals with vampires, and brings in a proper horror feeling to the story.

"...and then what happened?"

"...and then what happened?"