Coda

/ I vividly remember the events of September 11th. I was at my high school’s library, on one of the computers when I came across the news on a news site, and over the course of the afternoon, we learned that it was no accident, but a deliberate attack against the country. I remember being concerned that we didn’t know who did it, until the news began to shift over the next couple of days to the Middle East. In my 10th grade history class, we listened to the radio. The road was dead silent as the commentators spoke about the event. That day has defined the existence of my generation, in every single facet of life, as we’ve watched the towers tumble into two wars across the world, while our domestic society has undergone major shifts and changes that we’ve gone along with in the name of security and safety. One man changed the world, and he’s now dead.

I vividly remember the events of September 11th. I was at my high school’s library, on one of the computers when I came across the news on a news site, and over the course of the afternoon, we learned that it was no accident, but a deliberate attack against the country. I remember being concerned that we didn’t know who did it, until the news began to shift over the next couple of days to the Middle East. In my 10th grade history class, we listened to the radio. The road was dead silent as the commentators spoke about the event. That day has defined the existence of my generation, in every single facet of life, as we’ve watched the towers tumble into two wars across the world, while our domestic society has undergone major shifts and changes that we’ve gone along with in the name of security and safety. One man changed the world, and he’s now dead.

I’m not sure what I felt while listening to NPR late at night, when the rumors that Bin Laden was killed by US Special Forces in Pakistan. There’s a certain amount of relief, given the significance of the actions, but quite a bit of emptiness at the news. Bin Laden is now gone, and as the head of a terrorist group that’s killed thousands of people, I’m happy to see that he won’t be able to contribute to the overall direction and leadership, which will undoubtedly save lives in the future. At the same time, his death won’t bring back all those who’ve been killed across the world, and it won’t stop the momentum on the movement that he started.

Major political events have a certain momentum that keeps them going, and the death of Bin Laden ultimately won’t stop because their leader has been killed. It’s a setback, to be sure, just as when any organization loses their leader, they lose their particular guidance and leadership. Undoubtedly, there is some form of contingency plan on the part of Al Qaida to shift power around, and hopefully, it’s not well thought out or planned to any good degree, so that the transfer of power will be inefficient and slow down whatever plans they have coming up. That being said, Al Qaida certainly does have a population of people who support their goals and the means that they use to bring about their intended ends, and for that reason, it’s clear that the fight against terrorist activities will continue.

Hopefully, though, his death will help to further delegitimize Al Qaida as a credible entity in the eyes of those who are sympathetic to their ends. The uprisings across the Middle East have demonstrated – in part – that peaceful protest can help to gain what the people want, that violence doesn’t always have to happen. There’s no direct comparison between the efforts used to attack the US and to overthrow some of the Northern African – Arabic leaders, but there’s certainly the demonstration of alternatives. That being said, some of his supporters have already vowed violence in revenge: we’re not out of the woods yet.

Undoubtedly, we’ll see a couple of dramatic narratives on the events of the 1st, covering the planning that went into the raid that took Bin Laden’s life: I’ll be interested in seeing everything that happened leading up to it. I’ve already read a number of fascinating accounts between the White House and the military, in a real intelligence story that involved a lot of moving parts and elements. I’m rather surprised to see some of the news point to Guantanamo Bay as a source for some of the information that helped lead to the raid. It’ll be interesting to see the aftermath in the years, and that despite the stigma that the place represented to the outside world, some parts of it proved to be useful to the security of the country. It’s hard to remember at times that there are elements that we don’t see, and it’ll be interesting to see the final cost vs. the benefit that we attained from it.

The wars in Afghanistan will continue on as well, although with the death of Bin Laden, I’m guessing that there will be a bit less support for the conflict, and its impact on global affairs will be interesting to see. The people who supported Bin Laden’s world view of a strict non-secular state ruled by his strict (and flawed) interpretation of Islam are still around and seeking to implement their views in various points around the world. Afghanistan is one place, where the country’s government allowed an attack on the United States from Bin Laden. However, the US presence in Afghanistan, and the United States’ role in world affairs should be reexamined to determine where force should be used. The core mission in Afghanistan was to depress the abilities of Al Qaida to the point where it is no longer a threat to the United States: that would seem to be further along today, but it’s far from over. Our efforts against the insurgency in Afghanistan should be evaluated, to determine whether they are a threat to the country, or to consider whether we’re changing the core mission to something far more different, which has grave consequences and implications for our stance in the world.

This feels less like a victory, and more like a stepping stone in what has turned into a long and terrible struggle. At points, it feels like we’ve lost our way, our focus and sight of what we’re out to do, but hopefully, this incident will remind us of the reasons why this happened in the first place. I for one, don’t want to think of the last ten years that helped to define the world as something of a wasted opportunity to learn and improve upon our future. If anything, hopefully the death of one evil individual will help to bring about a brighter tomorrow.

Each year, the Colby Symposium awards the Colby Award to a first notable book from an author that deals fundamentally with the nature of warfare and contributes substantially to the field. During the awards dinner this year, executive director and Norwich University Alum, Carlo D'Este said that it was rare that the entire committee universally agrees on a single book, but that this was the case for the 2011 prize, going to Karl Marlantes, with his first acclaimed novel, Matterhorn.

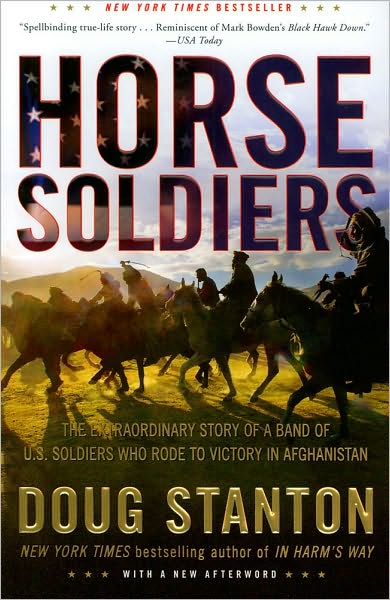

Each year, the Colby Symposium awards the Colby Award to a first notable book from an author that deals fundamentally with the nature of warfare and contributes substantially to the field. During the awards dinner this year, executive director and Norwich University Alum, Carlo D'Este said that it was rare that the entire committee universally agrees on a single book, but that this was the case for the 2011 prize, going to Karl Marlantes, with his first acclaimed novel, Matterhorn. The third talk of the Colby Symposium featured author Doug Stanton, author of the widely acclaimed New York Times bestseller

The third talk of the Colby Symposium featured author Doug Stanton, author of the widely acclaimed New York Times bestseller  The second presentation in the Colby Symposium at Norwich University was titled 'Afghanistan: America's Second Vietnam or its First Victory over Al Qaida?', by Jack Segal. Segal is the Chief Political Advisor to the NATO Joint Force Command Commander, General Wolf Langheld. He is a distinguished figure, having served two tours in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division during the Tet Offensive and again with the 25th Infantry Division, where he earned the Bronze Star and Meritorious Service Medal. Since the war and subsequent education, he's held numerous posts in the US Diplomatic service, playing key roles in the negotiations with the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the US and the USSR, and was named the first US Consul General in central Russia in 1994 and became the Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Lynn Davis in 1995. Following that, he worked with the National Security Council at the White House as the director for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, and worked with the White House's Kosovo group. in 1999, he became the NSA Director for Non-Proliferation, and joined NATO in 2000. He is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the US National Defense University. To say that he's had a distinguished and important role in foreign affairs is a bit of an understatement.

The second presentation in the Colby Symposium at Norwich University was titled 'Afghanistan: America's Second Vietnam or its First Victory over Al Qaida?', by Jack Segal. Segal is the Chief Political Advisor to the NATO Joint Force Command Commander, General Wolf Langheld. He is a distinguished figure, having served two tours in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division during the Tet Offensive and again with the 25th Infantry Division, where he earned the Bronze Star and Meritorious Service Medal. Since the war and subsequent education, he's held numerous posts in the US Diplomatic service, playing key roles in the negotiations with the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the US and the USSR, and was named the first US Consul General in central Russia in 1994 and became the Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Lynn Davis in 1995. Following that, he worked with the National Security Council at the White House as the director for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, and worked with the White House's Kosovo group. in 1999, he became the NSA Director for Non-Proliferation, and joined NATO in 2000. He is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the US National Defense University. To say that he's had a distinguished and important role in foreign affairs is a bit of an understatement.