Space Exploration and the American Character

/ Historian Dr. Michael Robinson, of the University of Hartford, opened his talk with a William Falkner quote that helped frame the 1961-1981 Key Moments in Human Spaceflight conference in Washington DC, held on April 26th through April 27th: “The past is never dead. It's not even past.” The first talks of the day dealt extensively with the narrative and drive behind space travel and exploration, painting it as much of a major cultural element within the United States as it was one of scientific discovery and military necessity. In a way, we went to space because it was something that we’ve always done as Americans.

Historian Dr. Michael Robinson, of the University of Hartford, opened his talk with a William Falkner quote that helped frame the 1961-1981 Key Moments in Human Spaceflight conference in Washington DC, held on April 26th through April 27th: “The past is never dead. It's not even past.” The first talks of the day dealt extensively with the narrative and drive behind space travel and exploration, painting it as much of a major cultural element within the United States as it was one of scientific discovery and military necessity. In a way, we went to space because it was something that we’ve always done as Americans.

The Past

Dr. Robinson started with a short story of a great endeavor that captured the imagination of the public, one that brought in a lot of rivalry between nations on a global scale, advanced our scientific knowledge, and where high tech equipment helped bring valiant explorers to the extremes. Several disasters followed, and the government pulled back its support, yielding part of the field to private companies. If asked, most people would describe the space race of the twentieth century, and while they would be right, what Robinson talked about was the race for the North Pole. In 1909, American explorer Robert Peary claimed to have reached the North Pole, becoming the first known man to do so. While there are reasons to doubt or support Peary’s travels, Robinson makes some interesting points in comparing the North Pole to that of the space expeditions.

Robinson described a culture of exploration that’s existed in the United States since its inception, but took pains to make a distinction between the frontier motif that has permeated science fiction, and the realities that we’ve come to expect from going into orbit. Television shows have undoubtedly aided in the excitement for space research and exploration, but they’ve incorporated elements that have great significance for American audiences: Star Trek, for example, had been described as a ‘Wagon train to the stars’, while Firefly has likewise been described as a ‘Western in space’, to say nothing of films like Outland, Star Wars, and numerous other examples. In his 2004 address that helped outline America’s space ambitions, President George W. Bush noted that “the desire to explore and understand is part of our character”. Other presidents have said similar things, and it’s clear that there’s a certain vibe that it catches with the American voter.

It makes sense, considering the United State’s history over the past centuries: Americans are all newcomers, and as Robinson said, the west was a place to settle. The arctic, and space, really aren’t, and distinctions should be made between everything. Historically, both space and the arctic have much smaller footprints of human interactions. It’s a difficult area to reach, and once people are there, it’s an incredibly hostile environment that discourages casual visits.

The American West, on the other hand, is very different for the purposes of imagery for space travel. During the great migration during the 1800s, it was relatively cheap for a family to travel out to vast untapped territory: around $500. Additionally, once people reached the west, they found a place that readily supported human life, providing land, food, and raw materials. The American west was transformed by mass migration, helping to vastly expand the U.S. economy during that time, while leading to a massive expansion of the federal government and to the Civil War. Space, on the other hand, isn’t so forgiving, and like the arctic, doesn’t yield the benefits that the west provided.

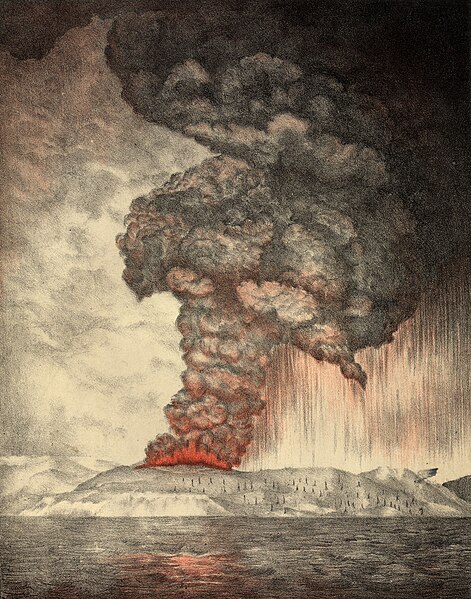

The explorations into the arctic gives us a sense of where space can go and how expectations from the public and the scientific community can come into line with one another. The polar explorations absolutely captured the imagination of the public: art exhibits toured the country, while one of the first science fiction novels, Frankenstein, was partially set in the North. However, what we can learn from the arctic is fairly simple: we abandon the idea of development in the short to mid future. Like the arctic, space is an extreme for human life, and the best lessons that we can glean for space will come from the past experiences that we’ve had from other such extremes: exploration in areas where people don’t usually go. This isn’t to say that people shouldn’t, or can’t go to the ends of the Earth and beyond, but to prepare accordingly, in all elements.

The arctic provides a useful model in what our expectations should be for space, and provide some historical context for why we go into space. We shouldn’t discount the idea that the west and the country’s history of exploration and settlement as a factor in going into space.

The Space Age

James Spiller, of SUNY Brockport, followed up with talk about the frontier analogy in space travel, noting that the imagery conformed to people’s expectations, and that notable figures in the field, such as Werner von Braun, liked the comparison because it helped to promote people’s interest in space. The west connected and resonated with the public, which has a history and mythos of exploration. This goes deep in our metaphorical, cultural veins, linking the ideas of US exceptionalism and individualism that came from the colonization of the American continent. The explorations to the west, the arctic and eventually to space, came about because it appealed to out character: it was part of our identity.

The launch of Sputnik in 1957 undermined much of what Americans believed, not just on a technical scale, but seemed to confirm that a country with vastly different values could do what we weren’t, with everything that was going for us, able to do. In the aftermath of the launch, President Eisenhower moved slowly on an American response, to great dismay of the public. It was a shock to the entire country, one that helped to prompt fast action and pushing up the urgency for a red-blooded American to go into space. How could the individual, exceptional Americans fall behind the socialists, whose values run completely counter to our own? There had already been numerous examples of individuals who had conquered machines and territories, such as Charles Lindberg and Robert Peary and the Mercury astronauts followed. Indeed, for all of the reasons for why the West feels important to Americans, the space program exemplifies certain traits in the people we selected to represent us in space.

Spiller noted that the frontier of the west seems to have vanished: the culture towards the end of the 1960s and early 1970s fractured society and the idea of American exceptionalism: the Civil Rights movement discredited parts of it, all the while the United States seems to have lost its lead in the global economy as other countries have overtaken it. As a result, the message of space changed, looking not out, but in. President Ronald Reagan worked to revisit the message, as did President H.W. Bush. There have been further changes since the first space missions: a new global threat that actively seeks to curtail modernism, terrorism, has preoccupied out attention, and pushed our priorities elsewhere.

Going Forward

The last speaker was former NASA Historian Steven Dick, who looked at the relationship between Exploration, Discovery and Science within human spaceflight, pointing out distinctions between the three: Exploration implies searching, while Discovery implies finding something, while science leads to explanation. The distinctions are important because they are fundamental to the rhetoric, he explained, and that the last program to really accomplish all three was the Apollo program.

Going into the future, NASA appears to be at a crossroads, and its actions now will help to define where it goes from here on out. The original budget that put men on the moon was unsustainable, but only just, and that as a result, NASA at the age of fifty is still constrained by actions taken when it was only twelve. The space shuttle is part of a program that was not a robust agent of exploration, discovery or science. He pointed out that where programs like Apollo and the Hubble Space telescope have their dramatic top ten moments, the Space shuttle really doesn’t, because it’s a truck: it’s designed with indeterminate, multiple functions, ranging from a science platform to a delivery vehicle for satellites. This isn’t to discredit the advances made because of the shuttle, but when compared to other programs, it doesn’t quite compare. The space station, on the other hand, was well worth the money, but people don’t respond as well to pure science as they do exploration. Apollo demonstrated that science alone isn’t enough to sustain public interest.

As he said it, “exploration without science is lame, discovery without science is blind, and exploration without discovery or science is unfulfilled.” Going forward, any endeavors beyond our planet should encapsulate all three elements to capture the public’s imagination, and make the efforts to go beyond orbit worthwhile for all. However, manned spaceflight can accomplish so much more than robotic probes and satellites, especially for fulfilling the frontier motif that helps to define our interest in going into space: it seems hard to embody the traits that have helped inspire people to go further when it’s someone, or something, else doing the exploring.

Space, the final frontier, is an apt way to look at how manned spaceflight programs are looked at, and it certainly captures the imagination of people from around the world. While some of the direct imagry is misplaced, it's not a bad thing for people to capture, but it does help to remember the bigger, and more realistic picture when it comes to what the goals and expectations are for space. NASA, going forward will have to take some of these lessons to heart, reexamining its core mission and the goals that its working to put forward. Nobody in the room doubted that the money and the advances that have come forward as a result of space travel were worth the cost and risks involved, but they want it to continue forward far into the future. To do otherwise would mean giving up a significant part of who we are, because the traits that that have come to define our exploration beyond the horizon, to the North and high above us are elements that are worth celebrating: the drive to discover, to explore and to explain are all essential for the future.