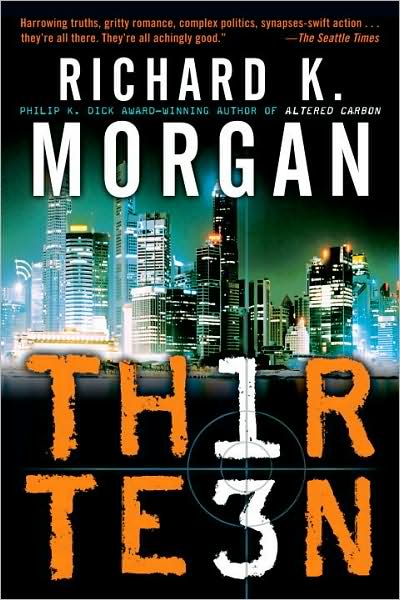

Thirteen

/

I finished my latest seminar on Sunday, which meant that for the next two or so weeks, I'll be completely free from academic readings until it all starts up again. I used the first day of my new found freedom to get around to finally finish one of the books that I've been picking away at for the last month and a half, Thirteen, by Richard K. Morgan.

Morgan is one of the best Science Fiction writers of the decade, and has consistently churned out fantastic works. My favorite book of his thus far has been his debut novel, Altered Carbon. His latest, Thirteen (Or Black Man, if you're overseas), is an interesting, complicated and thought-provoking read.

Thirteen follows some of Morgan's style that has been seen in some of his other works - indeed, this novel could easily take place in Takeshi Kovac's world, just an earlier, more recognizable version. There are elements common to both - a tough main character bred to fight, Carls Marsalis, a vast conspiracy, some harsh violence and sex thrown in for good measure. This is science fiction grown out of an adolescence fantasy - it came into adulthood with plenty of problems and it's not for kids, that's for sure.

Thirteen follows Marsalis as he's recruited by an international governmental organization, COLIN, to track down a renegade killer who escaped from a crashing inter-solar space ship after killing and eating the crew, and while on the ground, is picking off people, seemingly at random. Marsalis is tasked with this because the investigators believe that the killer is the same type of person as Marsalis - a Variant Thirteen, a genetically modified human, bred to be the baseline human, with all of the aggression and resourcefulness as our ancestors might have been twenty-thousand years ago before agriculture tamed us. Along the course of the book, a massive governmental and corporate conspiracy is uncovered, with far-reaching implications for all of the characters.

This was a facinating, although somewhat dense read. Morgan's writing makes me slow down and take things in far more slowly, and I suspect that I'll be thinking about everything over the next couple of days just to finish processing it. Like his other books, this one is complicated, which makes it all the more satisfying to read - very seldom now do I come across good SciFi that really makes me sit back and think to put the pieces together - oftentimes, it's far more simplistic and clear cut.

One of the more interesting points of the book was the near-future that it portrayed - clearly a result of the last eight or so years of American politics. In this future, the United States has split into several parts, the Rim (West Coast), The Confederated Republic aka Jesusland (The South) and the northeast, all taken with regional stereotypes and expounded upon. Jesusland, incidentally, takes its name from an internet diagram of the US after President George Bush's reelection in 2004 of the South as its own country, with the United States as Canada. It's not an unreasonable assumption to make, and its certainly a grim prediction, taken to extremes.

The original title of the book, Black Man, is a big portion of the book's plot, dealing with discrimination on an entirely new level - one's genetics. In this world, even though there are fairly good levels of equality, the color of one's skin has fallen away to one's genetics, where variants are the ones who have a whole new level of discrimination - to the point where they're not allowed to breed, are killed or persecuted for who they are and generally have a miserable life because the rest of the population doesn't like them. It's a chilling topic, and an interesting one at a time when there is much change heralded around the country, where the recent election is seen as proof-positive (to some extent this might be true, but it's only a start) that racial equality has been archived.

This is science fiction at its best. While there are some of the other usual standbys here - artificial intelligence, space ships, colonies on Mars, these are merely details to the larger story that folds in numerous excellent characters, motivations and a story on top of that. Morgan has crafted a fantastic story here that doesn't rely on gimmicks or require the reader to suspend their disbelief in any extended fashion - the story here is not only believable, but terrifying in the fact that it is guided by a future that could be. It is for this reason that Morgan is one of this generation's finest writers, and Thirteen, while slightly overlong and at times, a little too similar to his other books, is a good example of his abilities as a storyteller.

Now, onto the next adventure before reality once again sets in for another long eleven weeks.