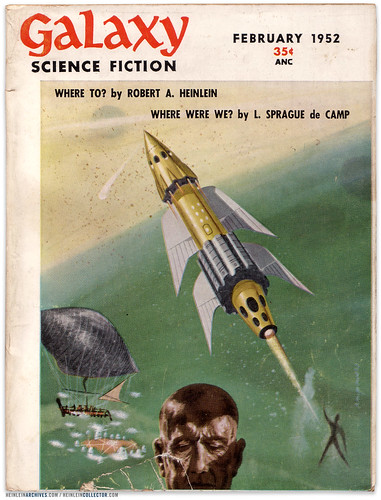

The Guardian Newspaper posted up an article about the label of Science Fiction when it comes to regular literature. Science Fiction as a broad genre has a number of connotations and images associated with it, for sure, but what exactly is the definition of the grouping?

According to Isaac Asimov, one of the greatest science fiction writers to ever live, Science Fiction is: Modern science fiction is the only form of literature that consistently considers the nature of the changes that face us, the possible consequences, and the possible solutions. (There are some other fantastic takes on this here.)

Over the past couple of years, as I have gotten more interested in the history and study of the genre, I'm leaning more towards an anti-genre sort of bias. I am a fan of the genre, and of the elements that commonly make it up - space ships, time travel, aliens, etc. What I find interesting though, is at how horror, science fiction and fantasy genres are generally grouped together, and how fans from one genre tend to be interested in the others.

According to the Guardian article, there are several authors whose books tend to fall under the SF/F genre heading, but aren't generally considered part of the genre, either by the publisher or the author. For example, the following paragraph raises some eyebrows:

"The Gone-Away World by Nick Harkaway has just had its paperback release, and is a tour-de-force of ninjas, truckers, Dr Strangelove-type military men, awe-inspiring imagery and very clever writing. It's also undeniably science fiction. Harkaway is an unrepentant fan of the genre, but his publishers William Heinemann have taken a lot of care not to market the book as such. Harkaway himself said in a recent interview: "I suppose the book does take place in the future, but not the ray-guns-and-silver-suits future. It's more like tomorrow if today was a really, really bad day.""

The last sentence is revealing one: "It's more like tomorrow, if today was a really, really bad day." Off the top of my head, I can list of a number of science fiction novels and films (Halting State, Children of Men, Wess'Har series, Firefly, etc), where this fits the description perfectly. Science fiction, in my opinion, is little different than most regular fiction, while just taking on a fantastic premise.

Margaret Atwood is somewhat misguided when she states: "Science fiction is rockets, chemicals and talking squids in outer space."

Science fiction is not just about rockets, chemicals and talking squids in outer space, although these can certainly be elements, but it is not the individual elements that really make up the core of a science fiction story. The core premise is the story. The best science fiction stories, the ones that hold up, are the ones that explore the human condition - not unlike most "literature". However, these elements do help to define the genre, and, if present in a story, help to define the novel. Stories with things like this are invariably labeled SF/F. It doesn't necessarily matter what the point of the book is.

Matthew Stover posted an interesting view up on a message board a couple months back:

"Literature is narrative fiction in which the author's intent is to express his individual vision of a fundamental truth of existence.

[Feel free to substitute other pronouns. I say "his" because, y'know, I'm a guy.]

The label of capital-L "Literature" is not a judgment of quality. It is a statement regarding the author's objectives. If the author's objective is simply (not "merely") to entertain or divert, the work in question is not Literature. It's still small-L literature (by definition), but that's not really what we're talking about. (I use the capital L to keep the distinction clear.)

And there's plenty of crummy Literature out there. It may be bad, but it's Literature nonetheless. "

At this definition, at a very broad angle, this encompasses a majority of SF/F genre stories, and separates out the ones that are essentially tie-in novels. The split is at the point where the view is either the author's, or someone else's. I'm content with this definition, because I've never seen the term Literature as something that automatically means quality. From there, everything can be broken down into the general elements that help to qualify the book. Science fictional type books tend to be grouped together with the ones that have the space ships, the aliens and things like that, but, above all, the story is such that the reader needs to be able to accept the premise, no matter what the story elements are. Battlestar Galactica and Firefly are two television shows that really did a good job at this - they took a situation, and focused on the way the characters reacted. Ron Moore has said that they didn't want to do a science fiction show, but they wanted a drama in space. It has science fiction elements, but that's not the focus.

Now, that might not be the main focus of these books that the Guardian has laid out, but they do contain science fiction elements. The article cites Jeanette Winterson with the following quote:

""People say to me, 'so is the Stone Gods science fiction?' Well, it is fiction, and it has science in it, and it is set (mostly) in the future, but the labels are meaningless. I can't see the point of labeling a book like a pre-packed supermarket meal. There are books worth reading and books not worth reading. That's all.""

I think she hit the nail on the head - essentially, it doesn't matter what the book's label is to the reader or storyteller - these labels seem to be more a thing concocted by publishers and booksellers in order to target certain audiences who might be more inclined to buy something with weird aliens and space ships as opposed to something else. That being said, even though Cormac McCarthy's The Road wasn't published or marketed as such, it's still gained quite a bit of a following in the SF/F genre crowd.

I'll always be a fan of the SF/F label though, despite the elitism and mockery that it might get - it's really the only genre that has a real geek following, and no matter the status that the genre gets from other authors and critics, it is still one of the sources, for me, of some of the best literature out there.