SyFy is headed to space, and it seems as though they're serious. Last week, they announced a 10-episode pickup of The Expanse, a series that will adapt (presumably) the first book from James S.A. Corey, . In the wake of the announcement, I've seen a lot of complaints from fans, noting SyFy's general track record with shows. Despite the last five years of distancing themselves from harder SF stories, this falls in line with the direction the channel is trying to lurch itself towards, shaking off their reputation for something better. It's about time, too.

SyFy is headed to space, and it seems as though they're serious. Last week, they announced a 10-episode pickup of The Expanse, a series that will adapt (presumably) the first book from James S.A. Corey, . In the wake of the announcement, I've seen a lot of complaints from fans, noting SyFy's general track record with shows. Despite the last five years of distancing themselves from harder SF stories, this falls in line with the direction the channel is trying to lurch itself towards, shaking off their reputation for something better. It's about time, too.

The Expanse is a good move for SyFy and the announcement that they've picked up the TV show fills me with quite a bit of optimism for the direction of the channel's future. Over the last couple of years, the channel has been talking quite a bit about returning to space, with news over the last couple of years of shows such as adaptations of Larry Niven's novel Ringworld and Sir Arthur C. Clarke's Childhood's End and shows such as Ascension and Defiance. So far, only Defiance (after a really long development period) has aired, and then, to tepid reviews and ratings. But, it's a start, and shows that the channel is starting to think about bigger, more serious projects.

In the mid-2000s, the show was indisputably one of the better outlets for speculative fiction on the small screen: long-running shows such as Stargate SG-1 and its spinoff, Stargate: Atlantis collectively ran for fifteen seasons, while Farscape and Battlestar Galactica, two very ambitious space dramas, had fairly good runs before being cancelled. With the cancellation of Ronald D. Moore's Galactica in 2009, the channel seemed to get nervous about shows set in space. Galactica's ratings had nosed down over the last two seasons (most likely due to some of the narrative stunts they took), and its follow-up successor, Caprica, set decades before, never found its voice or ratings, and was cancelled a year later. A third follow-up, Battlestar Galactica: Blood and Chrome, died a slow death as SyFy executives waddled on the decision to release it to the web or to television. Ultimately, it was burned off on YouTube, effectively ending the franchise for the channel. A third Stargate entry, Stargate: Universe, a grown up, broody and excellent entry never quite captured the same attraction as its predecessors, and ended with a frustrating cliffhanger at the end of Season 2.

SyFy pivoted, perhaps seeing the successes rival networks enjoyed with shows such as True Blood, and went in an urban fantasy and Sci-Fi lite direction. It's not really any surprise: the darker stuff hadn't really succeeded, and shows such as Eureka had done really well. Alphas, Warehouse 13, Lost Girl, Bitten and Being Human have all been developed, and dominated the network's offerings since 2009, alternatively earning praise from fans who enjoyed that type of story, and derided by those who missed the shows set in space.

All the while, SyFy expanded their offerings into reality TV, as well as the frequently-derided WWE on Wednesday nights. Often, their placement on the schedule has been explained as money makers for the channel (or, laughably, that it's a type of fantasy in and of itself), which in turn support the programming of the other scripted shows. I don't know that I've ever met anyone who's actually watched WWE on the channel.

Meanwhile, a revolution in scripted television erupted from various premium and network channels. TNT's Falling Skies, Fox's Fringe, CBS's Person of Interest, AMC's The Walking Dead, and HBO's Game of Thrones all came out, as well as show such as Awake, Under the Dome, Terra Nova, Revolution, Agents of SHIELD, Almost Human, Arrow, Orphan Black and Outcasts, to name a couple, while in non-Science fiction offerings, there's Once Upon a Time, Grimm, Supernatural, Sleepy Hollow, American Horror Story, Vampire Diaries, and others. Science Fiction TV, once largely limited to the SyFy channel, found new homes. While not all have been successful, it shows that there's a new appetite for speculative works on the small screen, and that such shows can not only do well, but do really well. SyFy, while it's had some success with their current offerings, hasn't had any hits on the same scale. They easily could have, with the right mindset.

Major projects such as The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones aren't easy projects to bring to television: they're big, elaborate, and cover subject material that's far from the material that SyFy was putting out between 2003-2008. They're ambitious (and I'll throw Person of Interest in there, too, as an example of what network channels *can* also do.) and have received a disproportionate amount of praise from critics and fans alike, all the while seeing their ratings go up as viewers keep watching.

It's clearly a balancing act: Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead take on popular properties and subject matter, all the while they're fairly well written and scripted. Others miss out: Awake, while fantastic, never caught on. Terra Nova was silly and stupidly expensive. Fringe lasted on critical glee, but wanted for viewers. Others just do really well with the right combination of characters and story, building year after year: Supernatural is well into its tenth year, and has a spin off in the works, while Arrow doesn't seem to be going anywhere but up (and also has a spinoff in the works).

SyFy's clearly got the vision for ambitious projects, but they're held back; from themselves. It's a business, and accordingly, the material they're turning out needs to be successful. However, it's always seemed as though this very risk-adverse mindset percolates down into what's being picked up. They say that you never make the shot that you don't take, and the channel has been on a course where they're only taking shots where the basket is five feet off the floor. Until Defiance, it's seemed that there's no sense of risk to the shows that they've tried, but rather gone back to the well time and time again for material that is proven to run with a certain audience.

In many ways, SyFy pivoted one way, anticipating an audience that they wanted to grasp, only to end up missing an audience that's since moved beyond the SyFy walls. Game of Thrones, Walking Dead, Orphan Black and Doctor Who have become the destination shows that would make a dynamite portfolio for a dedicated genre-channel. Even the ambitious Defiance feels like it's a compromise, existing only due to the momentum that a $100 million show causes. They've got a season 2, but the show won't take off until the show becomes something a bit more interesting. Shows such as Helix have demonstrated that they're ready to bring back some serious scripted drama.

Recently, SyFy seems to have realized something was up, and has been shaking off like a wet dog. VP Mark Stern, who oversaw the Battlestar-Defiance years at SyFy, and who's been replaced by Bill McGoldrick. McGoldrick shift earlier this year has come with a lot of talk about bringing SyFy back. In an interview with Adweek, he noted that they've realized that scripted drama is what the channel's reputation lives and dies by. The current reputation? Wounded from reality TV and crappy films. But, with the rise of shows such as Game of Thrones, they're starting to see serious offers for new shows, one of which was apparently The Expanse.

If there's a show that'll demonstrate that the channel is serious about bringing back 'proper' science fiction, it's Leviathan Wakes. The show has just about everything: spacecraft, epic world-building, military science fiction, conspiracies, and a huge cast of interesting and diverse characters. It's large, hits all of the right notes, and it comes with a built in audience of readers who've made the books hits. The first novel was nominated for the Hugo Award, and along with a bunch of shorter entries in the series, an additional three novels were ordered after the first three. The fourth book in the series, Cibola Burn, hits this summer, this time as a more expensive hardcover novel (as opposed to trade paperback, like its preceding three books.)

Moreover, SyFy seems to realize that story's paramount. Rather than putting together a pilot and worrying about ordering a full, 22-episode season, they've committed to a run of ten episodes - enough time to tell the story, but not so much that they'll have to really stretch their special effects budget. In addition to The Expanse, SyFy has recently announced a limited 12 Monkeys series and Ascension, a limited series about a group of colonists, all the while cutting back on the B films.

Most of the complaints genre fans have had about SyFy are true. The channel's shifted direction and gone the safe route, and accordingly, they've really missed out on both the opportunity to do great things, but also hitched themselves to the wrong horse, one that's slowly running down. The Expanse has the potential to be an innovating move that can get the channel restarted with good stories, and can bring back an audience that they really want to attract. Already, shows such as Alphas, Being Human and Warehouse 13 have been wound down and ended, while SyFy is keeping shows like Lost Girl and Haven (which picked up a 2-season, 26 episode order) to have a balanced set of offerings for the foreseeable future. If you're going to shake off a reputation, you've got to start somewhere.

There’s also a level of caution here. I don’t think fans should expect a return to the same SciFi channel that existed in the early 2000s. The landscape has changed, and accordingly, so has viewer tastes and viewing habits. Hopefully, we’ll be seeing a new channel that takes both storytelling and genre seriously, recognizing exactly what makes a good show that’ll not only do well season to season, but help the channel’s reputation and build on its audience year to year, which will mean more excellent projects will be attempted. More importantly, SyFy needs to learn to take risks. Even for projects that aren’t necessarily successful, the effort not only counts, but helps all involved figure out what to do next, in theory making things better in the future.

The Expanse is far from certain: it's an ambitious project to run, and likely expensive. But, I'm optimistic. It's got just about everything that science fiction fans have been asking for, and in an adaptation model that's worked in the past. Let's hope that the show-runners will do the books justice, but more importantly, tell a great story.

Ursula K. Le Guin is one of science fiction's greats: her stories Left Hand of Darkness, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Dispossessed rank among the genre's best works, and she moves easily between science fiction and fantasy, writing things that science fiction authors had barely touched before she came onto the scene. To say she was influential is to undersell one's words.

Ursula K. Le Guin is one of science fiction's greats: her stories Left Hand of Darkness, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Dispossessed rank among the genre's best works, and she moves easily between science fiction and fantasy, writing things that science fiction authors had barely touched before she came onto the scene. To say she was influential is to undersell one's words.

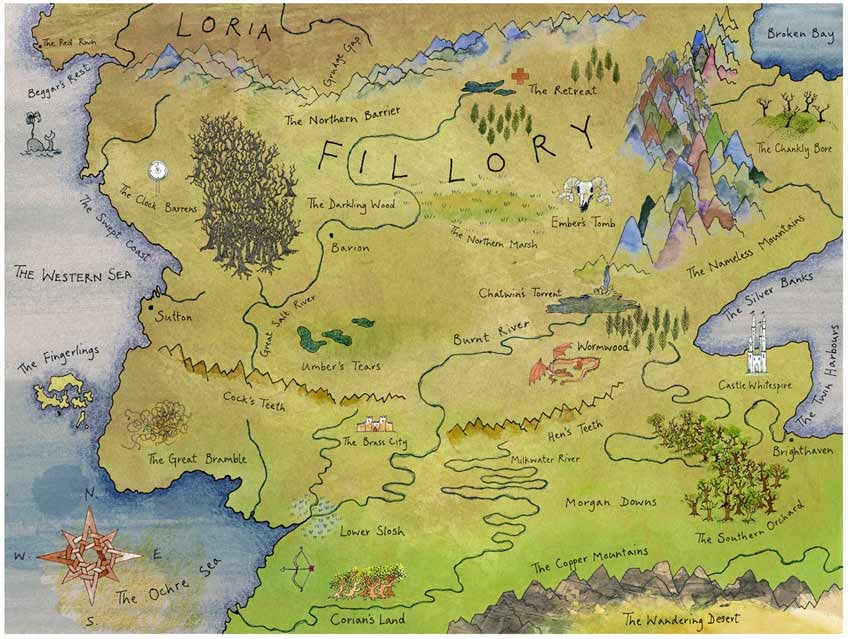

It's always cool to find previously unknown authors while doing research. Recently, I came across a relatively unknown fantasy author who had some close ties to some of the giants in fantasy: Christopher Plover. Famous for his Fillory and Further series, he's relatively unknown today. Recently, his works seem to have inspired one recent series of books, The Magicians trilogy, by Lev Grossman, who's latest book, The Magician's Land, came out earlier this week.

It's always cool to find previously unknown authors while doing research. Recently, I came across a relatively unknown fantasy author who had some close ties to some of the giants in fantasy: Christopher Plover. Famous for his Fillory and Further series, he's relatively unknown today. Recently, his works seem to have inspired one recent series of books, The Magicians trilogy, by Lev Grossman, who's latest book, The Magician's Land, came out earlier this week.

One of the first major SF novels that I picked up was Dune. Something about the copy at the library was striking: a figure against a desert. I tore into it and to this day, I can still visualize various parts of the book. It got me thinking about science fiction in ways that I hadn't before, and I still count it as one of my favorite books. I've never read the sequels: I never wanted to be disappointed or let down by the other novels (much like I've never read the 2nd and 3rd installments of the Ringworld and Foundation trilogies).

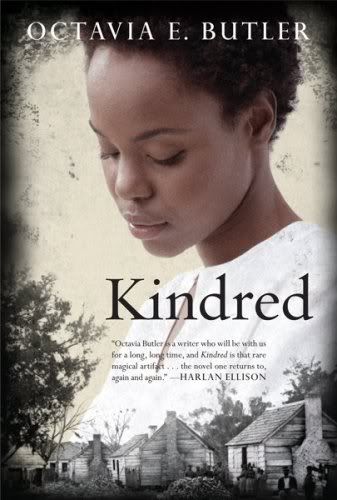

One of the first major SF novels that I picked up was Dune. Something about the copy at the library was striking: a figure against a desert. I tore into it and to this day, I can still visualize various parts of the book. It got me thinking about science fiction in ways that I hadn't before, and I still count it as one of my favorite books. I've never read the sequels: I never wanted to be disappointed or let down by the other novels (much like I've never read the 2nd and 3rd installments of the Ringworld and Foundation trilogies). For years, I've had friends tell me that I should be reading Octavia Butler's works, especially Kindred. I actually own a copy, and it's been sitting on my shelves for years, waiting for me to pick it up. When it came to the point where I'd start writing about the 1970s, it was pretty clear that Butler would be one of the authors that I'd be covering, and I picked up the book as part of my research. She's a powerful author, and I'm a little sad that I didn't read the book earlier. Researching Butler's life is fascinating, and it's becoming clear to me that some of the genre's most important works emerge from outside of it's walls.

For years, I've had friends tell me that I should be reading Octavia Butler's works, especially Kindred. I actually own a copy, and it's been sitting on my shelves for years, waiting for me to pick it up. When it came to the point where I'd start writing about the 1970s, it was pretty clear that Butler would be one of the authors that I'd be covering, and I picked up the book as part of my research. She's a powerful author, and I'm a little sad that I didn't read the book earlier. Researching Butler's life is fascinating, and it's becoming clear to me that some of the genre's most important works emerge from outside of it's walls. Ringworld is a novel that's always stuck with me. I picked it up alongside authors such as Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Robert Heinlein, and other authors from that point in time. Foundation and Dune are two books that are among my favorites, but Ringworld has long been the best of the lot. It's vivid, funny, exciting and so forth. Reading it again recently in preparation for this column, I was astounded at how well it's held up (as opposed to Foundation) in the years since it's publication, and I can't wait to read it again. Plus, that cover is just beautiful.

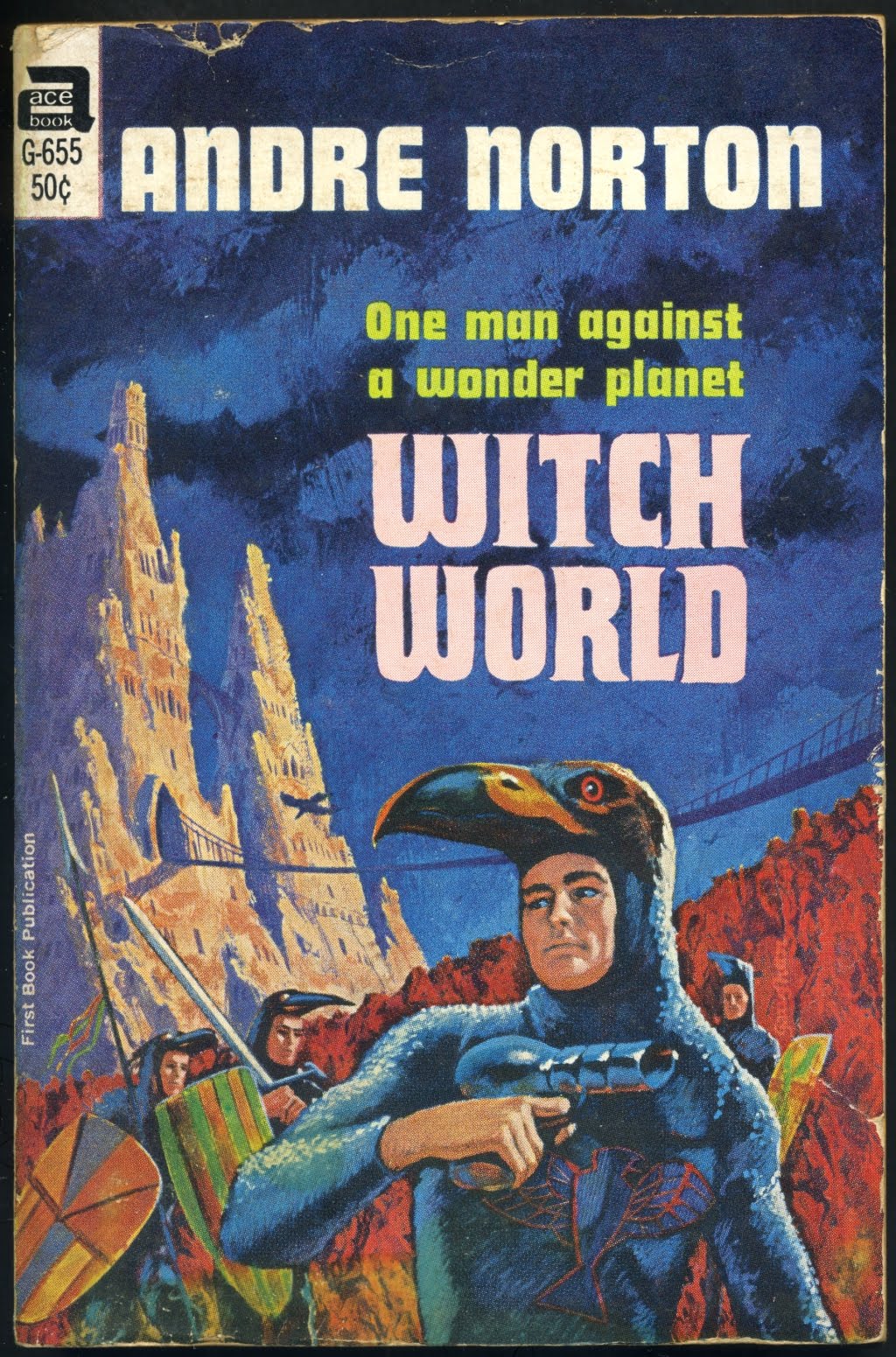

Ringworld is a novel that's always stuck with me. I picked it up alongside authors such as Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Robert Heinlein, and other authors from that point in time. Foundation and Dune are two books that are among my favorites, but Ringworld has long been the best of the lot. It's vivid, funny, exciting and so forth. Reading it again recently in preparation for this column, I was astounded at how well it's held up (as opposed to Foundation) in the years since it's publication, and I can't wait to read it again. Plus, that cover is just beautiful. When I worked at a bookstore (the now defunct Walden Books), I had a co-worker that loved Andre Norton. I'd never read any of her books throughout High School, although I was certainly familiar with her name. I wish now that I did.

When I worked at a bookstore (the now defunct Walden Books), I had a co-worker that loved Andre Norton. I'd never read any of her books throughout High School, although I was certainly familiar with her name. I wish now that I did. As I've been writing this column, I've realized that there's points where I have to move ahead and skip authors, or, after some reflection, research and writing, that I missed someone critical. Over the last couple of months, I've been realizing that not covering L. Frank Baum has been a drastic oversight, and that at the next available opportunity, I need to cover him and his wonderful world of Oz.

As I've been writing this column, I've realized that there's points where I have to move ahead and skip authors, or, after some reflection, research and writing, that I missed someone critical. Over the last couple of months, I've been realizing that not covering L. Frank Baum has been a drastic oversight, and that at the next available opportunity, I need to cover him and his wonderful world of Oz.

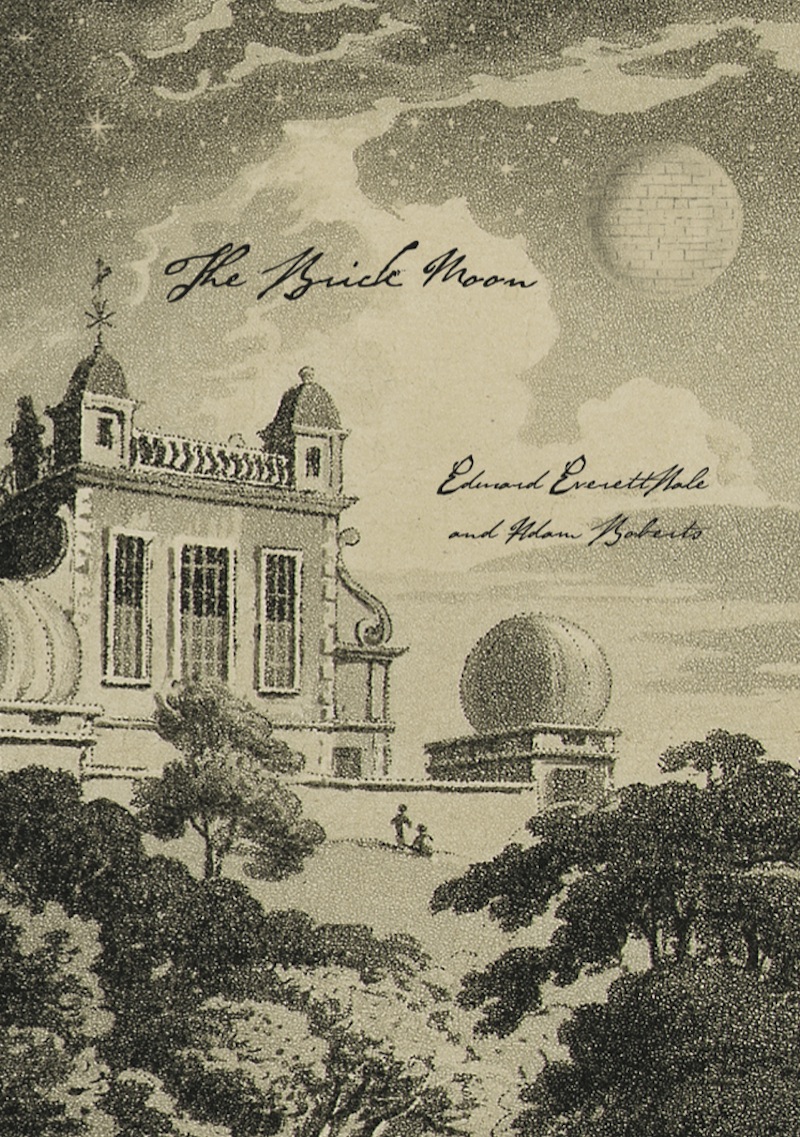

I've got a bit of a bonus installment for my column on SF History. I've got a limited amount of space that I've got to work with for Kirkus, and as such, I've had to blow past a couple of things. Fortunately, with Jurassic London's new release of The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale, I've had the opportunity to circle back and write about this particular novel.

The Brick Moon is the first science fiction story that uses the idea of an artificial satellite, and it's an excellent example of what science fiction is: extrapolation into the near future. In this instance the need for a navigational beacon in the skies. It's a cool premise, and in one fell swoop, Hale comes up with the idea for a satellite, communications satellite and space station. (Yes, Clarke came up with the idea as well. His invention is notable because it wasn't in SF, but a non-fiction speculation).

I've got a bit of a bonus installment for my column on SF History. I've got a limited amount of space that I've got to work with for Kirkus, and as such, I've had to blow past a couple of things. Fortunately, with Jurassic London's new release of The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale, I've had the opportunity to circle back and write about this particular novel.

The Brick Moon is the first science fiction story that uses the idea of an artificial satellite, and it's an excellent example of what science fiction is: extrapolation into the near future. In this instance the need for a navigational beacon in the skies. It's a cool premise, and in one fell swoop, Hale comes up with the idea for a satellite, communications satellite and space station. (Yes, Clarke came up with the idea as well. His invention is notable because it wasn't in SF, but a non-fiction speculation).

I've had a passing fascination with McCaffrey's books over the years, even as I never really dabbled in them. (I owned one book, Dragonflight, years ago.) I was always somewhat intimidated by the sheer size and scale of the series, and I was always more interested in SF than I was Fantasy (although now, I realize that that was a bit misguided.) Anne McCaffrey was always an author I was aware of: one of the female authors alongside the Asimovs, Herberts and Heinleins in my high school library.

I've had a passing fascination with McCaffrey's books over the years, even as I never really dabbled in them. (I owned one book, Dragonflight, years ago.) I was always somewhat intimidated by the sheer size and scale of the series, and I was always more interested in SF than I was Fantasy (although now, I realize that that was a bit misguided.) Anne McCaffrey was always an author I was aware of: one of the female authors alongside the Asimovs, Herberts and Heinleins in my high school library.

I've been a fan of Game of Thrones since I first caught it a couple of years ago, and I've been impressed with the HBO series as I've continued to watch. When Season 1 hit, I pulled out my copies of A Song of Ice and Fire and started the first book, alternatively reading and watching the show. I've found the books to be a trial to get through, but I've ultimately enjoyed them.

I've been a fan of Game of Thrones since I first caught it a couple of years ago, and I've been impressed with the HBO series as I've continued to watch. When Season 1 hit, I pulled out my copies of A Song of Ice and Fire and started the first book, alternatively reading and watching the show. I've found the books to be a trial to get through, but I've ultimately enjoyed them. In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history.

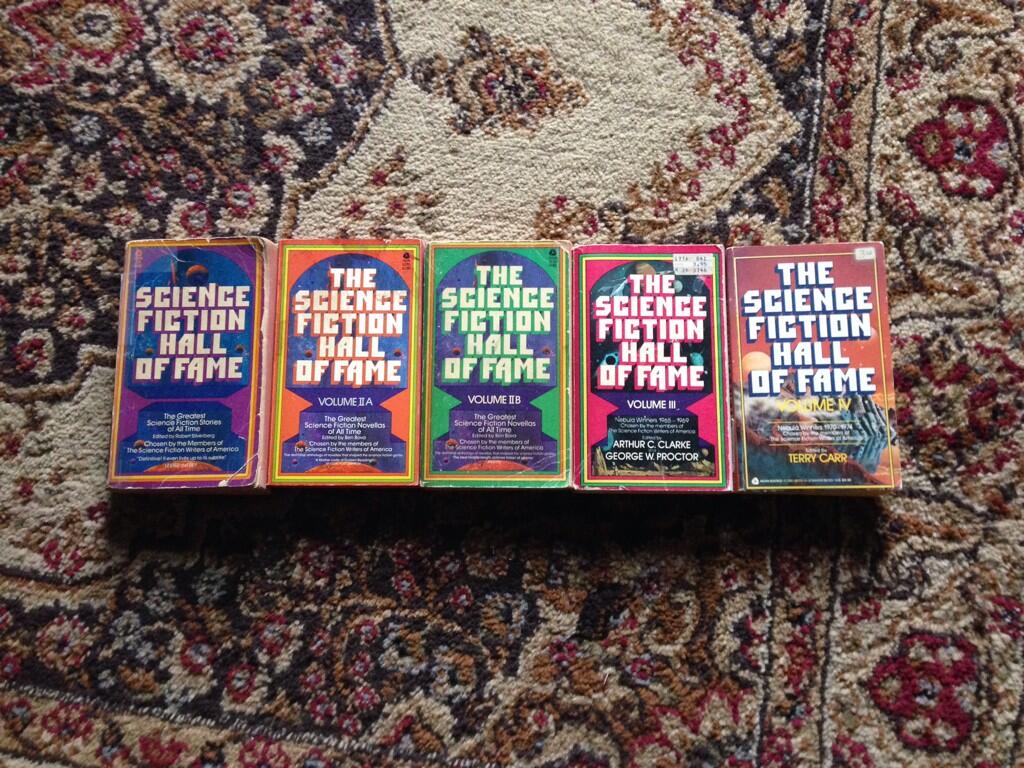

In my day job, I work with MBA students, and in the time that I've been doing that (and working at my regular job), I've gained a certain appreciation for how businesses function. When it comes to researching the column, looking at how a business functions has a certain appeal, especially since a major, unspoken element of SF History is really a sort of business history. One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him.

One of the stories that remains a favorite for me is Theodore Sturgeon's "Microcosmic God", which I tore through when I received a copy of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame way back in High School. Sturgeon became an author that I'd turn to pretty quickly whenever I picked up another anthology, and I've generally enjoyed all of the stories I've read from him. My Facebook wall blew up this morning with the following news: Star Wars author Aaron Allston collapsed at a

My Facebook wall blew up this morning with the following news: Star Wars author Aaron Allston collapsed at a