My Top 10 Games

/There’s a tweet going around about the games that are your personal top 10 video games of all time. It’s been fun to think about, especially as I’ve never really been a huge gamer. But looking back, there have been a bunch of games that have been a huge influence on how I’ve thought about stories and speculative fiction over the years. Here’s my personal top-10 list.

10. Titanfall 2

I really wanted to like the original Titanfall, but I really don’t like online games. It’s just not an experience I enjoy. But Titanfall 2 was fantastic. I love the story, love the gameplay mechanics, and I REALLY love the fantastic mechs. I’m bummed that there doesn’t appear to be a third game on the horizon. This feels like a world that could really challenge Halo, and I’d love to see more of this world.

9. Mario Kart / Super Mario Odyssey

When I bought my Nintendo Switch, I quickly bought Mario Kart on Megan’s advice. It quickly became a good game that we could all play as a family, and something that we could cart along on family trips for when we had downtime or something. I also picked up Super Mario Odyssey, which we’ve also played quite a bit. I haven’t beaten this game, but I’ve had a lot of fun watching Megan and Bram play it.

8. Diablo 2

When I worked at Camp Abnaki, there was one year where we had a shared computer in the equipment room. It was an easy assignment that left a lot of time for playing, (or playing after hours), and I spent a lot of hours at Camp, and later, when I got my own computer, playing through this. I’m not sure that I ever actually beat the game, but I did have a lot of fun leveling up my character.

7. Sim City 2000

Who doesn’t love Sim City? I love building epic cities in this, and all the fiddly bits that it requires, from raising / lowering taxes to playing with crime rates, roads, and zoning. I’ve played a bunch of mobile apps, but none of them really compare to this one.

6. Age of Empires

When I got my first computer, one of the games I got hooked on in high school / college was Age of Empires. That shouldn’t be a surprise — I studied history, and loved this take on it, building up civilizations and destroying my neighbors. I haven’t been able to play it for years, but I’ve been thinking of taking out my old computer to give it a spin.

5. King’s Quest VI

My friend Laura Hudson’s game list reminded me of this one, and it brought back a flood of memories. I’m pretty sure that this game came with our first Compaq computer in the mid-1990s, and I spent hours and hours exploring the Green Isles and reveling in its mashup of mythologies and fairy tales. I recently went and watched a play-through on YouTube, and was struck at how funny and clever it is. This was a hard one — it took me forever to finish it.

4. Pokémon Go

I missed the boat on Pokémon when I was a youth. Kids at summer camp played it, but I thought it was kind of dumb — I only played serious games like Dungeons & Dragons (where we accidentally exploded a moose). But when Bram got into the franchise via friends at daycare and school, I started playing the game with him, and it’s been a good motivation to get out and walk around quite a bit more.

3. Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening

This was probably the first video game that I ever really played, aside from the occasional visit to friends’ houses. My parents bought me a Game Boy, and it came with Zelda. It took me an embarrassingly long time to beat it, but I loved the game, and cried when I finally finished it. I went and replayed it just before Breath of the Wild came out, and it holds up nicely. I’d wanted to see a BOTW-style remake, but I’ll certainly be playing the 3D remake that’s coming later this year.

2. Halo / Halo: Reach / Halo: ODST

Halo was the first time I really got into gaming. It came out when I was a summer camp counselor at Camp Abnaki, and every summer for years, I played with my friends while we had downtime. I love military science fiction, so the power armor and FPS thing works for me, but the controls and gameplay were intuitive, the design was great, and it’s a neat story in a much larger narrative. I’ve since really gone on to love Halo: ODST for its story, as well as Halo: Reach for enriching the backstory. I’m a bit more lukewarm on Halo 3, but I do really enjoy Halo 4, especially its guns. Halo 2 and 5 are a hot mess, though.

1. Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

I can’t begin to imagine just how many hours I’ve spent playing this game. Not just in beating the main story, but just wandering around and exploring. This is a game that rewards curiosity, and walking, running, and riding across this fantastic version of Hyrule never feels like wasted time. I played this a lot with Bram, who watched and helped me with the puzzles and shrines, an experience that I’ll treasure forever. On top of that, the design and artwork is stunning, the gameplay is incredibly good, and the shrines and quests are wonderful.

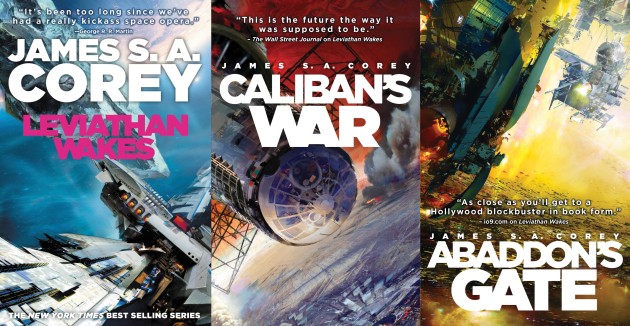

So, there's this book series that I've really enjoyed - The Expanse. I read the

So, there's this book series that I've really enjoyed - The Expanse. I read the

Over on Barnes and Noble's SciFi & Fantasy blog, I've got one of the biggest articles I've ever written: the Evolution of James S.A. Corey's series, The Expanse. This has been in the works for several months now, and it's really exciting to see it hit the light of day.

Over on Barnes and Noble's SciFi & Fantasy blog, I've got one of the biggest articles I've ever written: the Evolution of James S.A. Corey's series, The Expanse. This has been in the works for several months now, and it's really exciting to see it hit the light of day.