A while ago, I wrote about Larry Niven and his novel Ringworld for Kirkus Reviews. In doing so, I interviewed Mr. Niven, and he was kind enough to answer my questions about the genesis of the book. Here's our conversation:

A while ago, I wrote about Larry Niven and his novel Ringworld for Kirkus Reviews. In doing so, I interviewed Mr. Niven, and he was kind enough to answer my questions about the genesis of the book. Here's our conversation:

Andrew Liptak: You're well known for your 'Known Space' stories. What prompted you to link them together as you wrote, and how did this affect the stories as you wrote them?

Larry Niven: Heinlein and Anderson and others had done linked stories. It seemed an obvious labor-saving move. Equally obvious: if the story idea didn’t fit my universe, build another for it.

Often the effect was that a story written for its own sake generated more stories.

Lately the various series are generating stories in other minds.

AL: How did you come to open up Known Space to other authors?

LN: James Patrick Baen suggested doing that. I told him that Known Space was mine and I wouldn’t share. Five minutes later I was saying, “We could open up the Man-Kzin Wars. I don’t do war stories.” It all derived from that: fifteen volumes of the Kzinti, and then five written with Ed Lerner.

AL: Ringworld is arguably one of your best known novels: what can you tell me about how this story was conceived and written? What was the writing, submission and publication process like?

LN: I was gearing up to terminate the Known Space series when I thought of Ringworld. I think I did the obvious but at this late date I’m no longer sure. The obvious: take the equator out of a ping-pong-ball Dyson sphere—the only useful part—spin it up and terraform the inside.

I was visiting bibliophiles when I borrowed a text and got the formula for spin gravity. Otherwise I’d have used bad math to write bad scenery.

I was at Madiera Beach at the Knights’ writers conference, when I thought of the Eye Storm. I tried to describe it to Betty Ballantine. Maybe it got through.

I wrote the ending as quick as I could. It felt like the book was getting huge.

That cover was done from my sketch, but by someone who just didn’t get it. I’ve seen much better Ringworld illos since.

AL: How did your background in mathematics help you with writing and describing the book and Ringworld?

LN: I don’t think the math helped as much as the mathematician’s way of thinking. Building logic towers from premises wrung out of thin air. Mathematics is a game.

AL: Ringworld won the Hugo and Nebula in 1971, Ditmar in 1972 and placed 1st in the Locus poll that year: what was the winning streak like for you?

LN: Unique. I haven’t won a Hugo since 1976. I only won the one Nebula. You should know that I worried about Ringworld. I was afraid it would be laughed off the stage.

AL: What do you think appealed to readers for such a reaction for the book?

LN: The Ringworld is a wonderful mental plaything. THE INTEGRAL TREES is better science fiction, but it’s not as easy to play with the ideas.

AL: You note in your introduction that you never planned to continue the Ringworld story, but fans prompted you do continue. How did you go about putting together Ringworld Engineers from there?

LN: It kind of shaped itself. Beginnings are difficult; I started Louis Wu at the bottom of a lost career, the opposite of Ringworld. I’d been ignoring the hominid races; I began building them. It ran from there.

AL: Do you have any future plans for Ringworld?

LN: No.

AL: Your novels are considered to be 'Hard Science Fiction', and I've heard stories about your first published story, Coldest Place in reaction to that (regarding Mercury). Who were your influences when it came to writing in this particular style?

LN: “Hard” science fiction was pretty soft when I started writing. FTL, psi powers, teleportation and many other notions were fair game. These days I try to hew closer to what we think we know. My influences were Poul Anderson, Jack Vance, Arthur C. Clarke, Fritz Leiber…all the greats of that era.

AL: Were there any real-world influences (such as the space race) on Ringworld or the Known Space books? How do you think the Mercury/Gemini/Apollo missions impacted Science Fiction as a genre?

LN: I was pretty ignorant of the facts of daily life, politics, history. I didn’t get into those matters until I started collaborating. So reality didn’t have much effect on my writing early on.

AL: What can you tell me about the Galaxy Magazine pro/anti war ad?

LN: They made me decide. I chose to win a war we were already fighting. The truth may be more complicated, but they wouldn’t let me sit it out.

AL: Can you tell me a little more about this? Who made you decide, the magazine? What was their motivations for placing such an ad?

LN: Damon and Kate Wilhelm Knight gathered writers to a mutual criticism circle, once a year. One year they invited the conservatives to stay out while their like minded colleagues formed that first list advising an end to the Vietnam War. I did not appreciate being treated so, and when Poul shaped a counterattack, I joined it.

AL: What was your relationship with the Dangerous Visions anthology? (Aside from publishing a story in it - I saw that you were thanked in the acknowledgements).

LN: I loaned Harlan money. (It was paid back.) And I wrote an early story.

AL: Ringworlds have become popularized artifacts in science fiction: are you pleased to see this idea take off? Where did the idea of a Ringworld come from?

LN: Sure I’m pleased to have influenced the field, that way and others. Sometime the whole field looks like an ongoing conversation covering centuries.

The Ringworld derives from Dyson (Dyson sphere) via SF writers (who took it for a ping pong ball 93,000,000 miles in radius, with a star at the center) to the notion that you can’t have gravity generators, so you have to spin the thing, but now the air and water all cover just the equator…

AL: Are we ever going to see an adaptation of Ringworld on the big or small screen? I saw that SyFy had announced it last year, almost a decade after they originally announced it.

LN: SyFy has cancelled again.

AL: That’s a shame. Do you hope to see an adaptation made?

LN: I might not live that long.

AL: There's a critical essay out there that compares Ringworld to The Wizard of Oz. Are these comparisons accurate or intended? Was Oz an influence for you?

LN: That critic convinced me completely. Yes, I loved the OZ books when I was in grade school, but I didn’t realize I was using the plot line. It just felt right.

AL: When did you first come across science fiction? Why have you remained a reader and writer in the genre?

LN: First there were fair tales (including the OZ books.) Then, Heinlein and a bunch of other writers of juveniles.

AL: Were you a magazine fan at all, or part of Fandom before you became a writer? If so, where there any authors that were a particular influence, stylistically?

LN: I was a magazine and anthology fan, but I’d barely heard of Fandom. When I knew I wanted to become a pro writer, I tracked them down.

AL: A friend of mine who's working on her PhD in soil ecology has two questions: In Bowl of Heaven, human intentions and behavior are misunderstood by the other sentient creatures they encounter, leading to conflict that could have been avoided if both species better understood one another. Do you think this also happens here on Earth, and if so, what implications does it have for efforts to preserve ecosystems and biodiversity? How could environmentalists and policy-makers benefit from reading Bowl of Heaven? How could the ideas explored in Bowl of Heaven help set research agendas for scientists studying animal behavior?

LN: Misunderstandings have caused conflicts through the ages, but less often today. Communications are better. Today conflict arises from real differences.

Biodiversity and ecosystems should be preserved…but won’t be until someone can make that economically feasible.

Reading Bowl of Heaven will make smart people smarter. The lessons are in there. Research agendas in animal behavior? I’m not sure. Ask Greg Benford.

There's been others championing Ringworld - Lev Grossman recently published a great look over at Time.

Over the last couple of years, I've gotten more and more interested in the pulp era of science fiction, particularly of the science-horror genre, dominated by the likes of H.P. Lovecraft and his circle of fellow authors. Recently, the New York Review of Books sent me a copy of a very interesting looking omnibus, The Rim of Tomorrow, by William M. Sloane, introducing me to a new author of cosmic horror.

Over the last couple of years, I've gotten more and more interested in the pulp era of science fiction, particularly of the science-horror genre, dominated by the likes of H.P. Lovecraft and his circle of fellow authors. Recently, the New York Review of Books sent me a copy of a very interesting looking omnibus, The Rim of Tomorrow, by William M. Sloane, introducing me to a new author of cosmic horror.

There's few institutions like Astounding Science Fiction or editors like John W. Campbell Jr. Together, they are probably responsible for much of the tone and content of the science fiction genre in its formative years. Thus, during the tumultuous years of the 1960s, the changes to the magazine are an interesting example of how science fiction was changing: shedding one image and adapting, while positioning itself for the future.

There's few institutions like Astounding Science Fiction or editors like John W. Campbell Jr. Together, they are probably responsible for much of the tone and content of the science fiction genre in its formative years. Thus, during the tumultuous years of the 1960s, the changes to the magazine are an interesting example of how science fiction was changing: shedding one image and adapting, while positioning itself for the future.

I've been a bit behind on updating about Kirkus Reviews posts. I've published two in the last month, one about Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game and the other about Margaret Atwood.

I've been a bit behind on updating about Kirkus Reviews posts. I've published two in the last month, one about Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game and the other about Margaret Atwood. I have a short post up this week at Kirkus Reviews. I've been looking at writing more about some of the women who wrote in the genre, and came across one, Clare Winger Harris, who seems to have been one of the earliest, at least under her own name. There's not much out there about her, but she proves to be a really interesting subject.

I have a short post up this week at Kirkus Reviews. I've been looking at writing more about some of the women who wrote in the genre, and came across one, Clare Winger Harris, who seems to have been one of the earliest, at least under her own name. There's not much out there about her, but she proves to be a really interesting subject. The idea of genre is a helpful and annoying one: people like to identify where things fit, particularly on bookshelves, but they don't want to be constrained by it. As we've seen over the course of this column, science fiction's character has vastly changed in the centuries of its existence, transforming and splitting into its own little factions over time.

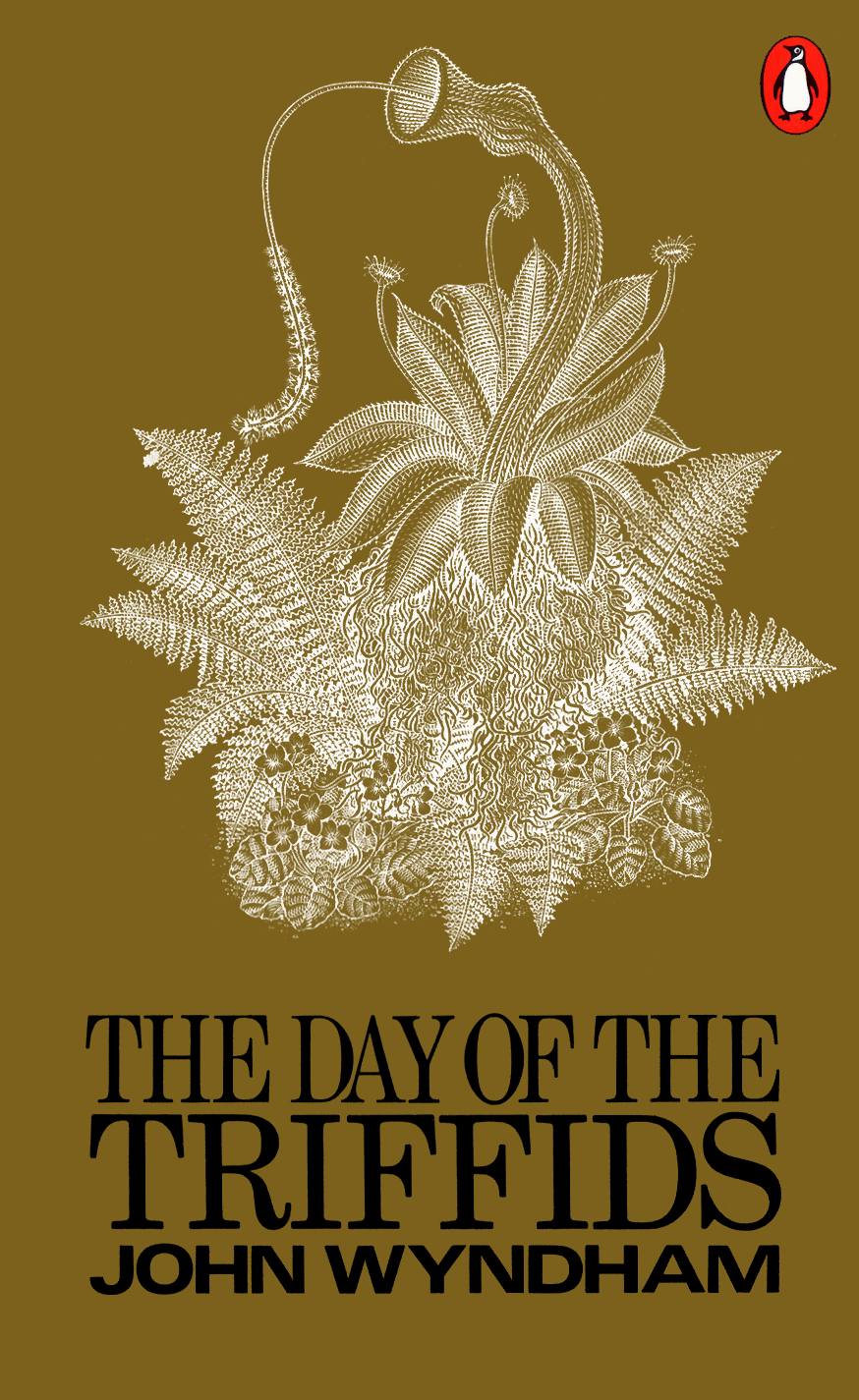

The idea of genre is a helpful and annoying one: people like to identify where things fit, particularly on bookshelves, but they don't want to be constrained by it. As we've seen over the course of this column, science fiction's character has vastly changed in the centuries of its existence, transforming and splitting into its own little factions over time. One of my favorite activities is to browse through used bookstores to see what turns up. I don't buy a lot of new science fiction novels anymore: It's worked out so that most of the books I want to read come to me for reviews (although I still buy my share of new books, usually from several of Vermont's fantastic indie bookstores), but there's something cool about an older paperback. One such recent purchase was a pair of John Wyndham novels, The Day of the Triffids and The Kraken Wakes. They're gorgeous Penguin editions with some outstanding cover art.

One of my favorite activities is to browse through used bookstores to see what turns up. I don't buy a lot of new science fiction novels anymore: It's worked out so that most of the books I want to read come to me for reviews (although I still buy my share of new books, usually from several of Vermont's fantastic indie bookstores), but there's something cool about an older paperback. One such recent purchase was a pair of John Wyndham novels, The Day of the Triffids and The Kraken Wakes. They're gorgeous Penguin editions with some outstanding cover art. I remember the moment very clearly: I was with my friend Erica at a writer's conference in 2001, when we learned that Douglas Adams had passed away. It was the first time I was really struck that an author I enjoyed would no longer write something, and we both commiserated over the book that really really loved: Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

I remember the moment very clearly: I was with my friend Erica at a writer's conference in 2001, when we learned that Douglas Adams had passed away. It was the first time I was really struck that an author I enjoyed would no longer write something, and we both commiserated over the book that really really loved: Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

Space Opera is a genre near and dear to my heart, and as I've written for Kirkus Reviews, it's clear that space opera is one of the genres that's been a central focus of science fiction: the idea of travelling through space and visiting new worlds is a particularly interesting one. Space Opera has changed over time, and one of the authors responsible for setting up some modern styling of it is Jack Williamson, who enjoyed a particularly long career as an author.

Space Opera is a genre near and dear to my heart, and as I've written for Kirkus Reviews, it's clear that space opera is one of the genres that's been a central focus of science fiction: the idea of travelling through space and visiting new worlds is a particularly interesting one. Space Opera has changed over time, and one of the authors responsible for setting up some modern styling of it is Jack Williamson, who enjoyed a particularly long career as an author. While I've written about books and magazines for this column, there's other mediums where science fiction lives: television and film. I haven't talked about that much for the column (given that Kirkus Reviews is primarily a book magazine), but there's some fascinating times when they've crossed over. One such case is one of the first science fiction television shows, which caught my interest based on the authors who wrote for it: Asimov, Clarke, Vance, and others. The show was Captain Video and his Video Rangers, and it's a neat program that forms a solid branch from the literature world to the television world, helping to bring about other major television shows that followed.

While I've written about books and magazines for this column, there's other mediums where science fiction lives: television and film. I haven't talked about that much for the column (given that Kirkus Reviews is primarily a book magazine), but there's some fascinating times when they've crossed over. One such case is one of the first science fiction television shows, which caught my interest based on the authors who wrote for it: Asimov, Clarke, Vance, and others. The show was Captain Video and his Video Rangers, and it's a neat program that forms a solid branch from the literature world to the television world, helping to bring about other major television shows that followed. My latest column on Kirkus Reviews combines a couple of things that I've been looking to talk about for a while now: how did major changes in the bookselling industry change how books were being written and sold to publishers?

My latest column on Kirkus Reviews combines a couple of things that I've been looking to talk about for a while now: how did major changes in the bookselling industry change how books were being written and sold to publishers? My latest post is up on Kirkus Reviews, this time pulling back from the trenches and looking at what my boss calls the 20,000 foot strategic picture. Throughout the column, I've largely looked at authors who've shifted the genre from point to point, but over time, I've started getting interested in the larger forces at play: the publishers and reading habits of Americans. As I work towards putting these columns towards a book, I've begun looking at some of the other influences outside of the arts world that have shaped SF.

My latest post is up on Kirkus Reviews, this time pulling back from the trenches and looking at what my boss calls the 20,000 foot strategic picture. Throughout the column, I've largely looked at authors who've shifted the genre from point to point, but over time, I've started getting interested in the larger forces at play: the publishers and reading habits of Americans. As I work towards putting these columns towards a book, I've begun looking at some of the other influences outside of the arts world that have shaped SF. Throughout my years of stalking the science fiction shelves of bookstores and libraries, there's been a trilogy of books that's always caught my eyes, but which I never quite picked up to read. They were Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy, with its distinctive covers which matched the titles of the books. I had attempted to get into Red Mars over the years, but never got very far.

Throughout my years of stalking the science fiction shelves of bookstores and libraries, there's been a trilogy of books that's always caught my eyes, but which I never quite picked up to read. They were Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy, with its distinctive covers which matched the titles of the books. I had attempted to get into Red Mars over the years, but never got very far. Last year, I was shocked to read that Iain M. Banks announced that he had cancer and was going to die within months. I had first come across him when I picked up Consider Phlebas, and several of its sequels when my Waldenbooks shut down and liquidated its stock: his books were amongst the first that I grabbed and stuck in the backroom to hold while we waited for the store to close. I really enjoyed the novel, although I've yet to really pick up any of the others. I was facinated by the depth and breadth of the Culture.

Last year, I was shocked to read that Iain M. Banks announced that he had cancer and was going to die within months. I had first come across him when I picked up Consider Phlebas, and several of its sequels when my Waldenbooks shut down and liquidated its stock: his books were amongst the first that I grabbed and stuck in the backroom to hold while we waited for the store to close. I really enjoyed the novel, although I've yet to really pick up any of the others. I was facinated by the depth and breadth of the Culture. C.J. Cherryh is an author that I've come across quite a lot, but was never one that I really ever got into. Recently, I've become more interested in her books, particularly Downbelow Station, which prompted me to take a look at her career. It's a facinating one that pulls in some of the legacies of her predecessors (such as Robert Heinlein and similar), and newer innovations that made her career different than that of her predecessors: she was primarily a novelist, rather than someone who started in the pulp magazines.

C.J. Cherryh is an author that I've come across quite a lot, but was never one that I really ever got into. Recently, I've become more interested in her books, particularly Downbelow Station, which prompted me to take a look at her career. It's a facinating one that pulls in some of the legacies of her predecessors (such as Robert Heinlein and similar), and newer innovations that made her career different than that of her predecessors: she was primarily a novelist, rather than someone who started in the pulp magazines. Joanna Russ wasn't an author I came across when I first came across science fiction: she was someone that I slowly became aware of more recently, when I started working at this on a more professional and critical level. Part of this came from friends who were interested and researching her, and over the last couple of years, I've gained an appreciation for the few works that I have read.

Joanna Russ wasn't an author I came across when I first came across science fiction: she was someone that I slowly became aware of more recently, when I started working at this on a more professional and critical level. Part of this came from friends who were interested and researching her, and over the last couple of years, I've gained an appreciation for the few works that I have read. Science Fiction publishing is full of strange characters, but there's one story that seems to really capture people's attention consistently: James Tiptree Jr., a brilliant figure who seemed to appear out of nowhere, earn a number of awards, and maintained a fairly elusive personality in science fiction circles. It wasn't until a decade of writing that it was revealed that Tiptree wasn't actually a guy: it was a woman named Alice Sheldon, with an utterly fascinating background: she had traveled the world, participated in the Second World War, worked for the CIA and had a PhD.

Science Fiction publishing is full of strange characters, but there's one story that seems to really capture people's attention consistently: James Tiptree Jr., a brilliant figure who seemed to appear out of nowhere, earn a number of awards, and maintained a fairly elusive personality in science fiction circles. It wasn't until a decade of writing that it was revealed that Tiptree wasn't actually a guy: it was a woman named Alice Sheldon, with an utterly fascinating background: she had traveled the world, participated in the Second World War, worked for the CIA and had a PhD. When I was in High School, I devoured Ender's Game and Starship Troopers, but it wasn't until I'd left graduate school that someone forced me to read The Forever War. When I did, I

When I was in High School, I devoured Ender's Game and Starship Troopers, but it wasn't until I'd left graduate school that someone forced me to read The Forever War. When I did, I  A while ago,

A while ago,