Machine Man, Max Barry

/ Max Barry released a video trailer for his latest novel, Machine Man, which completely and utterly sums up the tone of the entire novel. It's bitterly comedic, which is something I've come to expect from the writer.

Max Barry released a video trailer for his latest novel, Machine Man, which completely and utterly sums up the tone of the entire novel. It's bitterly comedic, which is something I've come to expect from the writer.

Machine Man is easy to sum up in a single sentence: it's about a man who cuts off his own limbs to replace them with parts he makes himself. It's one of the few examples of cybernetics in fiction that I can think of readily (Robocop also comes to mind), and it's a fun, easy look at some of the problems associated with identity and of making one's self better.

Charles Neumann is a scientist for a major company that has its fingers everywhere, and after locating his missing cell phone, he accidentally looses his leg. After working on recovering, he builds his own prosthesis, and finds that he'd like a matching pair. The company is more than willing to accomodate him: he's able to build some incredible technology, and the team that he's assembled goes through breakthrough after breakthough, building all types of things to make people *better*.

The story is somewhat predictable, and Neumann begins to lose some of his humanity as he replaces more and more parts, putting his relationship with Lola in risk as he circles the drain.

I liked this book: it's a quick, fairly easy and immersive read, and I found myself going through a hundred pages a sitting before finishing it. Written as an online serial to complete the first draft, the book feels remarkably consistant, although there are points towards the end where it begins to drag and slow down a bit.

Machine Man is also very funny, something I remembered enjoying from the other book I have from Barry, Jennifer Government. It's a blistering satire at times, jumping right out of the gate with the problems associated with a missing smartphone that sets Charles down the path of becoming more machine than man. Anyone who's owned an iPhone knows exactly what I'm talking about, and Barry brings up some good points between the two characters: Lola has mechanical parts in order to survive from day to day (an artificial heart), while Charles simply feels like he's a robot anyway, and wants the convinience and advances that robotics would bring him.

While it's funny, pithy and sarcastic, it feels like there's a good point to be made here: with everything that technology allows us, how much is too much, but more importantly, would we be able to recognize our overdependance on technology if we even realized that we were depending on it too much? This isn't a case of Barry standing on the front porch yelling for kids to get off his lawn, but one of rationing and realizing that there can be too much of a good thing, and the book balances a fine line between cyberntic fight scenes and morality, telling a straightup tale of human nature.

It's a little frustrating at points for me personally, especially running up to the end, when it's clear that most of the characters, despite their tendencies to make clear and rational decisions, to continue making the same choices, despite what it's cost them. It's pointed out to Lola that she has had problems recognizing a person's character and getting too involved with their struggle, even to her detriment, something that largely happens again when she meets Charlie. The same is true for Charlie, who keeps building pieces of himself, no matter what it costs. It's a relevant message, one that bears paying close attention to.

At the end of the day, Barry's put together a solid, fun science fiction thriller that doesn't feel like a science fiction story: it feels contemporary (and, much to my annoyance, it's shelved as such, which made it difficult to find in Barnes and Noble), and highly realistic, as if it's a future that we're living in right now.

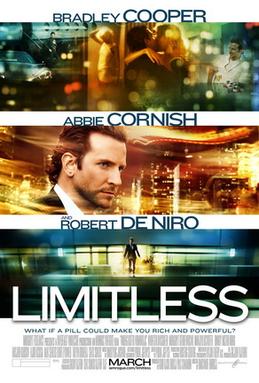

We all want to be smarter, faster, improvements upon ourselves, the 2.0 version of our percieved out of date opeating systems. Like the best science fiction stories, Neil Burger's 2011 film Limitless is a film that looks to the very basics of human life, and watches where people inevitably mess it up with our own flaws. Based off of a 2001 book, The Dark Fields, by Alan Glynn, the film looks at what people do if they can operate with nothing holding them back.

We all want to be smarter, faster, improvements upon ourselves, the 2.0 version of our percieved out of date opeating systems. Like the best science fiction stories, Neil Burger's 2011 film Limitless is a film that looks to the very basics of human life, and watches where people inevitably mess it up with our own flaws. Based off of a 2001 book, The Dark Fields, by Alan Glynn, the film looks at what people do if they can operate with nothing holding them back.

A disclaimer: a copy of this book was provided by Blake, who had consulted me at one point about the military elements of the story.

A disclaimer: a copy of this book was provided by Blake, who had consulted me at one point about the military elements of the story.

This morning, I pulled out of my driveway and angled down U.S. Route 2, shifting onto VT Route 12 and through the hills of Berlin and Northfield to work. Tonight, I’ll likely make my way back on the same route, but I very well might take I-89N up from Northfield to Berlin. Never once, in any of the hundreds of trips that I’ve made along that route, have I ever seriously wondered where the roads came from. They’ve always been there, for better or for worse, and they make up the foundation upon which our modern lives exist. Earl Swift’s latest book, The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways, is a grand story that I’ve long wanted to read about: the development of the American highway and interstate system.

This morning, I pulled out of my driveway and angled down U.S. Route 2, shifting onto VT Route 12 and through the hills of Berlin and Northfield to work. Tonight, I’ll likely make my way back on the same route, but I very well might take I-89N up from Northfield to Berlin. Never once, in any of the hundreds of trips that I’ve made along that route, have I ever seriously wondered where the roads came from. They’ve always been there, for better or for worse, and they make up the foundation upon which our modern lives exist. Earl Swift’s latest book, The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways, is a grand story that I’ve long wanted to read about: the development of the American highway and interstate system. This year has seen several novels that I've come to with high expectations, only to be let down by a poor story, characters and writing. M.M. Buckner's latest novel, The Gravity Pilot, falls into this trend. Despite a strong premise and interesting world, the book is a lack-luster read, one that left me frustrated and awaiting for the final chapters.

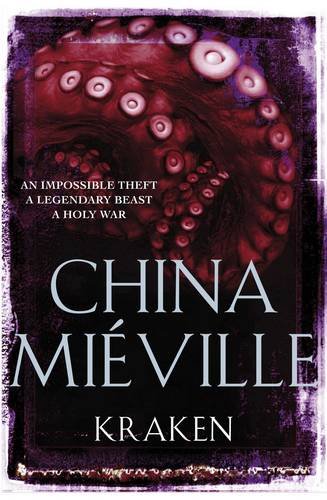

This year has seen several novels that I've come to with high expectations, only to be let down by a poor story, characters and writing. M.M. Buckner's latest novel, The Gravity Pilot, falls into this trend. Despite a strong premise and interesting world, the book is a lack-luster read, one that left me frustrated and awaiting for the final chapters. China Miéville has been on a bit of a tear to explore every genre through his books. With Embassytown, he turns from his earthbound adventures of late (The City and The City and Kraken), and goes into deep space, for a truly alien world.

China Miéville has been on a bit of a tear to explore every genre through his books. With Embassytown, he turns from his earthbound adventures of late (The City and The City and Kraken), and goes into deep space, for a truly alien world.

On the airplane over to Europe, I was a bit puzzled by the screening of X-Men 3: The Last Stand, but because I couldn't sleep, I watched it, and remembered just how bad it was. Where the first two X-Men films were fun, and fairly well done, the third felt rushed, overcooked, with no cohesive storyline, characters and action that didn't make sense, but with some definite promise to it. It's unfortunate that it was such a train wreck, and it put me off from the follow-up Wolverine film, which I've still not seen. Thus, the news that there was another X-Men film coming out simply didn't register, until it became fairly clear that this was going to be a film that was somewhat different.

On the airplane over to Europe, I was a bit puzzled by the screening of X-Men 3: The Last Stand, but because I couldn't sleep, I watched it, and remembered just how bad it was. Where the first two X-Men films were fun, and fairly well done, the third felt rushed, overcooked, with no cohesive storyline, characters and action that didn't make sense, but with some definite promise to it. It's unfortunate that it was such a train wreck, and it put me off from the follow-up Wolverine film, which I've still not seen. Thus, the news that there was another X-Men film coming out simply didn't register, until it became fairly clear that this was going to be a film that was somewhat different. In Will McIntosh's debut novel, Soft Apocalypse, the world as we know it ends with a whimper, not a bang. The end of America and the rest of the world comes out of our over indulgence, use of resources and all of the problems in society reaching a dull roar that tears down the world as we know it. This story takes a small cast of characters and looks at them over a much longer point of time than more novels, providing a unique perspective on what the future might hold.

In Will McIntosh's debut novel, Soft Apocalypse, the world as we know it ends with a whimper, not a bang. The end of America and the rest of the world comes out of our over indulgence, use of resources and all of the problems in society reaching a dull roar that tears down the world as we know it. This story takes a small cast of characters and looks at them over a much longer point of time than more novels, providing a unique perspective on what the future might hold.

Climate change is here to stay. It’s a bit of a foregone conclusion at this point, given the rise of human industrialized society and the scientific evidence that is increasingly supporting the idea that we’ve influenced how we have changed our climate to the point where it’ll cause problems for life as we know it. As such, it’s a little surprising that there isn’t more of an impact in the science fiction realm. I think that’s about to change, as that reality sinks in a little more, and it seems that there are a growing number of books that are starting to come out about the topic, which I’m rather happy about. In 2009, Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Windup Girl was released to great acclaim, set in a post-oil world, and is something of a novel that demonstrated what type of story really works.

Climate change is here to stay. It’s a bit of a foregone conclusion at this point, given the rise of human industrialized society and the scientific evidence that is increasingly supporting the idea that we’ve influenced how we have changed our climate to the point where it’ll cause problems for life as we know it. As such, it’s a little surprising that there isn’t more of an impact in the science fiction realm. I think that’s about to change, as that reality sinks in a little more, and it seems that there are a growing number of books that are starting to come out about the topic, which I’m rather happy about. In 2009, Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Windup Girl was released to great acclaim, set in a post-oil world, and is something of a novel that demonstrated what type of story really works.

If you like Space Opera, this will be the book for you: Leviathan Wakes, by author James A. Corey (a collaboration between Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck). Spanning much of our solar system, it's an epic story in a reasonably near future, with an excellently conceived of environment and a fun story that is both action packed and thoughtful. Leviathan Wakes is the embodiment of what good space opera should be: there's a bit of a scientific background that helps to inform the plot, but the focus of this story is on the characters and major events that blast the story forward.

If you like Space Opera, this will be the book for you: Leviathan Wakes, by author James A. Corey (a collaboration between Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck). Spanning much of our solar system, it's an epic story in a reasonably near future, with an excellently conceived of environment and a fun story that is both action packed and thoughtful. Leviathan Wakes is the embodiment of what good space opera should be: there's a bit of a scientific background that helps to inform the plot, but the focus of this story is on the characters and major events that blast the story forward. St. Patrick’s day is a good day to listen to one of my absolute favorite albums, Carbon Leaf’s Echo Echo. Released in 2001, this was one of my early introductions to the band, alongside their first major record label album, Indian Summer (also quite good). Amazon.com had released the album as a free download while I was in college, and the album became a regular on my rotation of songs on my iPod and computer playlists. Interestingly, it’s remained there since, and one of the few albums that I return to again and again.

St. Patrick’s day is a good day to listen to one of my absolute favorite albums, Carbon Leaf’s Echo Echo. Released in 2001, this was one of my early introductions to the band, alongside their first major record label album, Indian Summer (also quite good). Amazon.com had released the album as a free download while I was in college, and the album became a regular on my rotation of songs on my iPod and computer playlists. Interestingly, it’s remained there since, and one of the few albums that I return to again and again.

Last year, finally picked up my first China Miéville book, The City and The City, and was blown away by the story and world building that set the story in such an interesting location. At the same time, I’d picked up his latest book, Kraken, which had promptly been picked up by my girlfriend, who’s urged me to read it since. Kraken turns out to have been a very different book from Miéville’s prior work, and was one that sucked me in with his elegant prose and fascinating take on an alternate, hidden London.

Last year, finally picked up my first China Miéville book, The City and The City, and was blown away by the story and world building that set the story in such an interesting location. At the same time, I’d picked up his latest book, Kraken, which had promptly been picked up by my girlfriend, who’s urged me to read it since. Kraken turns out to have been a very different book from Miéville’s prior work, and was one that sucked me in with his elegant prose and fascinating take on an alternate, hidden London.