I dipped my toe into the world of Chinese science fiction over the course of this summer, as i did a bit work on my home. To keep myself on track and entertained, I began listening to a string of Clarkesworld Magazine’s podcasts — their fantastic translations from China. (In particular, “The Wings of Earth” by Jiang Bo, “Farewell Doraemon” by A Que , “Your Multicolored Life” by Xing He, and “To Fly like a Fallen Angel,” by Qi Yue) I’ve read stories from the China before: I wrote a post for Barnes and Noble about the history of Chinese science fiction, and through Ken Liu’s anthology, Invisible Planets, and of course, Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem (which I reviewed for Lightspeed Magazine a couple of years ago.)

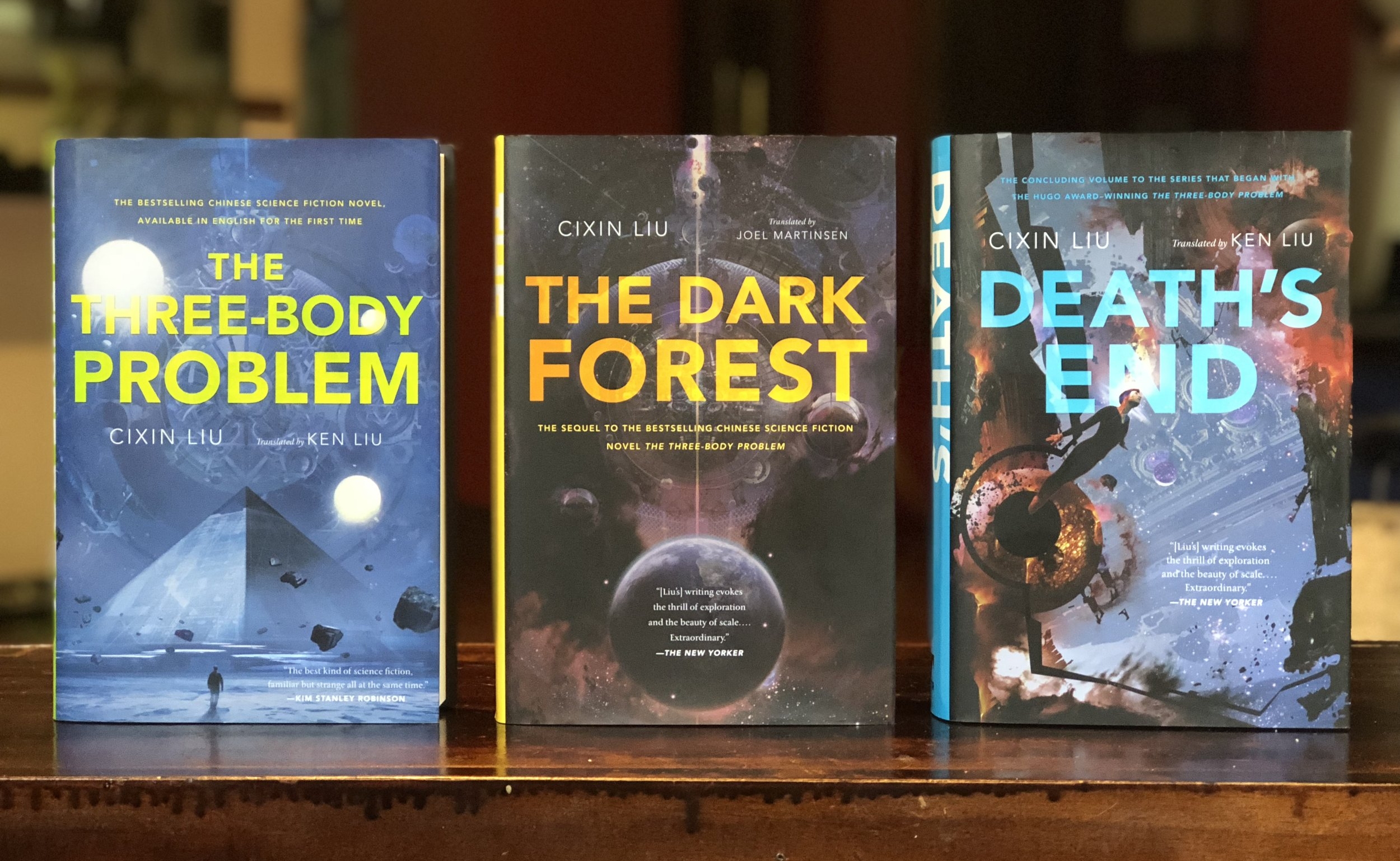

I’ve begun work on a new project for The Verge, and along with the stories that I had been listening to, I decided to go back to The Three-Body Problem and its sequels, which had been sitting on a shelf for a couple of years, books that kept telling myself that I’d pick up eventually. So, after I reviewed Liu’s novel Ball Lightning for The Verge, they were books that I picked up right away, to revisit that world. I blew through each of the three books in the trilogy, and I’m kicking myself for not reading them earlier.

The most impressive thing that I found with the trilogy as a whole was the scale that Liu was writing at. Reviews and blurbs for the series teased that it spanned the entire future: from the 1970s all the way to the heat death of the universe, and he manages to do that, in a really interesting way. Spoilers ahead.

The Three-Body Problem begins in the midst of China’s Cultural Revolution: a woman named Ye Wenjie watches as her father is killed during a riot. She’s sent first to a labor camp and then to an isolated scientific facility, where she’s able to put some of her astrophysics training to work. While there, she conducts some research, and ends up testing a way to amplify a radio signal to beam into the cosmos. She’s surprised, eight years later, when a representative of an alien civilization, the Trisolarans, contacts her, warning her not to respond to any further messages. Fed up with the human race, and with the treatment that she’s endured, she responds, allowing the Trisolarans to locate Earth.

Trisolaris, it turns out, is a harsh world: it orbits three stars in an unpredictable pattern, destroying civilizations over and over again. Now, the system knows where a stable, habitable planet is, and they’re bent on traveling to it. It’ll take them 450 years to reach Earth, however, and to prepare, they form a fifth column of like-minded Humans to prepare for their arrival. The Three-Body Problem jumps back and forth between various time periods, and in the present day, the Trisolarans send along a device called a sophon — a multidimensional supercomputer that interferes with advanced physics research, effectively stalling scientific progress to counter the Trisolarans.

In the first novel, humans uncover the Trisolaran plot, but are left with a conundrum: anything they do to prepare will be seen instantly by the Trisolarans. The next installment, The Dark Forest, we follow Earth’s various efforts as they work to counter the alien invaders, electing four individuals with immense resources to act as “Wallfacers,” who are tasked with formulating plans that only they know, in order to prevent the plans from falling into enemy hands. The book largely follows Luo Ji, a scientist who initially refuses, and after taking advantage of the resources, formulates a plan to “cast a spell” on a star — testing to see whether or not there are other observers in the galaxy. It turns out that there are, and it forms the basis for a sort of mutual self-destruction pact between Earth and the Trisolarans.

In the final book, Death’s End, the Trisolarans and Earth reach an uneasy balance during what comes to be known as the Deterrence era. This book largely follows a woman named Cheng Xin, who finds herself in the role of Swordholder — someone who maintains the deterrence that keeps Earth safe. When that fails, we follow as humanity prepares to take whatever means it can to ensure its survival.

That summary is just a tiny, thumbnail sketch of the entire series: Cixin covers an incredible amount of territory over the course of the trilogy. The Three-Body Problem is the most straight-forward of the trilogy. The Dark Forest and Death’s End each deal with incredible jumps in time as characters enter hibernation, and as society makes its own leaps and bounds technologically. Earth’s society swings between incredible austerity and poverty to utopian-like periods of high technology, and beyond. There’s really everything in this book, from massive space battles, political intrigue, and social commentary embedded in here. The books as a whole are a bit uneven: Cixin likes to devote a lot of time to exploring futuristic technologies and infodumps (which I don’t mind, but some people complain about), and there’s a lot of tangents that give me the impression that the entire trilogy could be tightened up quite a bit. But the adventure is in the ride, and that awesome scale really plays well here.

One of the biggest points that Cixin makes in this series is a grim answer to the nature of life in the universe: in all probability, there’s life beyond Earth — there’s just too many planets out there for us to be alone. Cixin’s world is teeming with life, and everyone is quiet. He likens the galaxy to a Dark Forest, in which there are many people, hidden from one another. The rise of one planetary civilization means a potential, existential threat others, and the moment that one becomes visible, they’re immediately in danger. The Trisolarans are certainly one threat, but Luo Ji realizes that there’s likely others, and that lighting up one’s location for the rest of the cosmos to see would mean a quick response from another, more powerful neighbor.

This actually happens — Death’s End has an gripping, and utterly horrifying example of what that looks like. It’s a brilliant scene, and it’s part of a larger culmination of the trilogy as a whole.

But what Cixin is doing is playing against the larger body of science fiction. There’s plenty of stories throughout the genre’s canon that imagines peaceful (and sometimes not so peaceful) coexistence with other aliens out there — the world of Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers and John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War come to mind, but those don’t come close to the grim world that Cixin portrays. With a veneer of hard physics limiting the characters, everyone in the galaxy is essentially moving around this dark forest, trying to avoid being spotted, for fear of being wiped out. In many ways, I think this series helps set a tone for science fiction that will follow: a new way to look at and conceptualize the universe around us.

This, to me, is big. There’s always been a sort of argument between the hard-SF crowd and the softer space opera circles between how to realistically portray the harsh nature of space, and Cixin’s trilogy essentially finds a newish way to look at the cosmos, somewhere between awe and wonder, while also recognizing that we’re an incredibly small part of the universe.