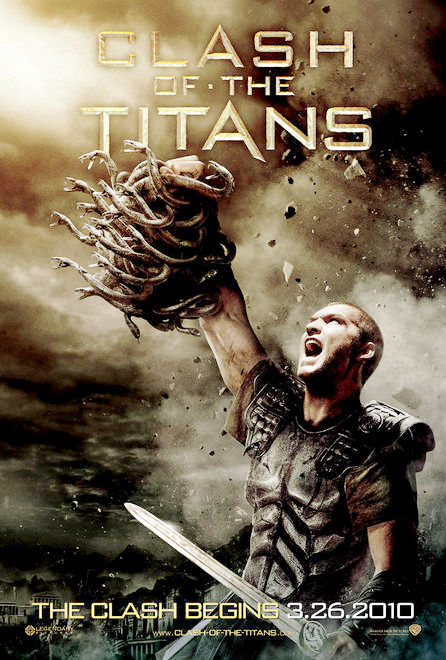

The Clash of the Titans

/

For Christmas last year, my girlfriend bought me a copy of Jason and the Argonauts, the 1963 Don Chaffey film that featured a number of technical innovations, the coolest of which was the skeleton fight scene. We both really enjoyed the film, including its fairly decent special effects, which I found to hold up quite well with the test of time. I've long been a fan of the various Greek and to a lesser extent, the Roman mythology. As such, I was really looking forward to the recent remake of Clash of the Titans.

This is not a movie that I had any major expectations of, and in that way, it completely met my expectations by being the film equivalent of a big, dumb Labrador. Very nice to look at, and quite a lot of fun, but really, really dumb. Clash of the Titans is a big, dumb movie. But quite a bit of fun to watch. The film had the requisite amount of action, some very nice lighting with a couple of the epic looking scenes that really scream 'Epic'. Where the film really succeeded though was where the production design and overall look and feel of the film: it looks like a concept artist's dream project. As the heroes set out from Argos to track down Medusa, they venture through forests to deserts to volcanoes, and there's quite a bit of really good scenery and setting here. What impressed me more was the crossing of the river Styx and the ferryman Charon. There was a large amount of detail there, with little touches that really made that stand out for me. Other scenes, such as the background of Argos and the Underworld itself worked just as well. Along the same lines, the Djinn, Sand-Demons with magical powers, which brings the film far more into the realm of fantasy than over any sort of adaptation of myth, were particularly fun to watch - constructs of dark magic and wood.

The action also really was a lot of fun to watch, with any number of monsters, soldiers and people waving swords at one another and attempting to kill each other. The camera work was good, and I have to say that the battle against the giant scorpions was something that kept me at the edge of my seat. The film presents itself as a completely over the top thrill that really is one of the few reasons to actually watch: it doesn't feel like it's taking itself seriously, from beginning to end, which I appreciated.

Still, I couldn't help but think that there were things that could have been done far better. The acting from some very good actors, such as Ralph Fiennes and Liam Neeson was abysmal throughout, and Sam Worthington continues his trend of fairly lack-luster performance from Avatar into the ancient times. The acting element was something that I wasn't too annoyed with, but at points, the story itself could have been tightened up quite a bit more, particularly when it came to the relationship between Zeus and Hades, which has essentially been likened to a Christianity-themed relationship, with Zeus taking on the part of God, and Hades, Lucifer. I can't really think of a good reason as to why this was done, but it's certainly a major departure from the mythos of the characters. (However, I have to continue to remind myself that this move as a whole is a major departure). What bothers me the most though, is that this film could have gone both ways, either a serious retelling of the myth, or a complete pulp version. Clash of the Titans as a whole falls somewhere in between. It's fun, but not as much fun as it could have been.