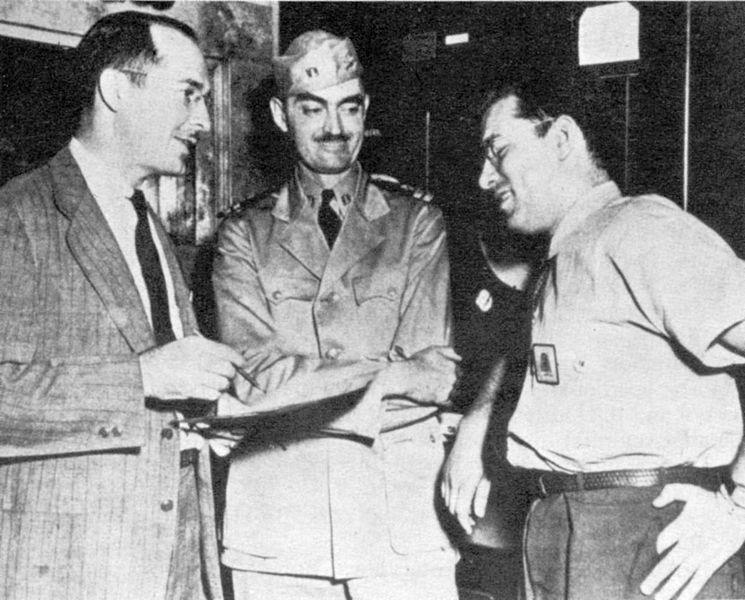

Asimov, de Camp and Heinlein at the Naval Air Experimental Station

/

I came across an interesting tidbit a while ago, while reading something about Robert Heinlein: he served as a researcher during World War II, alongside fellow SF authors Isaac Asimov and L Sprague de Camp. It's a neat intersection, and while their experiences don't yield any major works or revelations to the science fiction field, it does demonstrate the real inter-connectivity between authors working in the field.

At the NAES, Asimov, Heinlein and de Camp all worked on various experimental projects, working in the high-tech, cutting edge of R&D that's so often portrayed in the genre at the time. It's a neat story, one that tells quite a bit about each of the authors.

Read Asimov, de Camp and Heinlein at the Naval Air Experimental Station over on Kirkus Reviews.

Sources used:

I, Asimov, Isaac Asimov: this autobiography is an interesting one, and it's still just as smug and self-deprecating as his other one that I've read, It's Been A Good Life, but this one has quite a bit more when it comes to information.

It's Been A Good Life, Isaac Asimov: this is a bit redundant, but it's a decent, if annoying read on Asimov's life. The man really was a bit of a twit.

Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century, Volume 1 (1907-1948), William Patterson: This biography is astonishingly good, and incredibly detailed and dense with information. Patterson does an excellent job getting Heinlein's life (the first part!), in day by day detail.

Time and Change: An Autobiography: L Sprague de Camp: This autobiography from de Camp is an excellent one. Rich in detail, lacking the ego, and generally provides an excellent look at who de Camp was.

I came across something interesting in the last couple of years: The best of the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, was written by a longtime SF author, Leigh Brackett, who had written the film's first draft before passing away. When I had been

I came across something interesting in the last couple of years: The best of the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, was written by a longtime SF author, Leigh Brackett, who had written the film's first draft before passing away. When I had been

Last year, I largely covered the formation of the Science Fiction genre, going from some of the notable early authors, and running up to the pulp era. There's a lot that I haven't covered, and at some point, I'm going to be going back and filling in some of the holes behind me. There's an enormous number of authors and editors out there, and there's always going to be new things to add and explore.

Last year, I largely covered the formation of the Science Fiction genre, going from some of the notable early authors, and running up to the pulp era. There's a lot that I haven't covered, and at some point, I'm going to be going back and filling in some of the holes behind me. There's an enormous number of authors and editors out there, and there's always going to be new things to add and explore. Women are vastly underrepresented in science fiction circles, especially back in the pulp days. While many point to

Women are vastly underrepresented in science fiction circles, especially back in the pulp days. While many point to  For my last Kirkus Column, I talked about

For my last Kirkus Column, I talked about  I got into science fiction through my love of Star Wars. The geeky primer had already been charged with earlier stories, but George Lucas's films pushed my geeky little mind into overdrive.

I got into science fiction through my love of Star Wars. The geeky primer had already been charged with earlier stories, but George Lucas's films pushed my geeky little mind into overdrive. In the middle of November, I talked about Tolkien's WWI experiences and their impact into their writing. With the live action adaptation of The Hobbit released into theaters soon, it makes sense to look at how The Hobbit was written in the first place. It's an interesting story, with a bunch of twists and turns.

Go read

In the middle of November, I talked about Tolkien's WWI experiences and their impact into their writing. With the live action adaptation of The Hobbit released into theaters soon, it makes sense to look at how The Hobbit was written in the first place. It's an interesting story, with a bunch of twists and turns.

Go read  Sometimes, stories find you when you least expect them. I began this column thinking that I would find Tolkien's experiences in war as an almost superficial influence on his later stories, only to find the complete opposite. Tolkien went to war and underwent pure horror. He witnessed a terrible war from the front lines, and found most of his friends dead when he left. It's little wonder that he felt that his creative spirit was dampened by it.

Sometimes, stories find you when you least expect them. I began this column thinking that I would find Tolkien's experiences in war as an almost superficial influence on his later stories, only to find the complete opposite. Tolkien went to war and underwent pure horror. He witnessed a terrible war from the front lines, and found most of his friends dead when he left. It's little wonder that he felt that his creative spirit was dampened by it. With October's Horror duo over with, I decided that it was time to shift gears again in preparation for the really big fantasy event of the year: The Hobbit, and thus focus on some of the background on Fantasy literature, which I haven't really focused on thus far. Like Science Fiction, context for the development of Tolkien's works relies on an earlier look at what came before, and the notable author that I became interested in was George MacDonald, who really jump started the Fantasy genre by creating a number of modern fairy tales that inspired many fantasy authors that came before him. He's not a household name like Mary Shelley, Jules Verne or H.G. Wells, but he was no less influential in his works, which went on to inspire authors such as J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis.

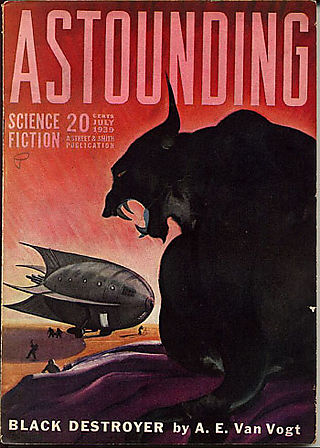

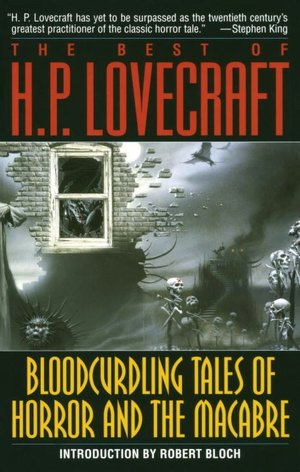

With October's Horror duo over with, I decided that it was time to shift gears again in preparation for the really big fantasy event of the year: The Hobbit, and thus focus on some of the background on Fantasy literature, which I haven't really focused on thus far. Like Science Fiction, context for the development of Tolkien's works relies on an earlier look at what came before, and the notable author that I became interested in was George MacDonald, who really jump started the Fantasy genre by creating a number of modern fairy tales that inspired many fantasy authors that came before him. He's not a household name like Mary Shelley, Jules Verne or H.G. Wells, but he was no less influential in his works, which went on to inspire authors such as J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. With October a traditionally - horror themed month capped with Halloween, it seemed appropriate to follow up Bram Stoker and Dracula with another notable horror author: H.P. Lovecraft. Hugely influential in the horror genre, Lovecraft is an author that I got into while in college, with a course on Gothic Literature. I've found Lovecraft's stories to be delightfully macabre, and living in Vermont, I can identify with his love of the sheer age of the location, and can see just why this corner of the country is so suited for horror fiction.

With October a traditionally - horror themed month capped with Halloween, it seemed appropriate to follow up Bram Stoker and Dracula with another notable horror author: H.P. Lovecraft. Hugely influential in the horror genre, Lovecraft is an author that I got into while in college, with a course on Gothic Literature. I've found Lovecraft's stories to be delightfully macabre, and living in Vermont, I can identify with his love of the sheer age of the location, and can see just why this corner of the country is so suited for horror fiction.

I had a gap in the schedule, and it seemed like a good time to start getting ready for October. Somewhere, I decided that I wanted to take a look at a broad swath of a genre, and because I was working on the pieces for October (Dracula), it seemed as good a time as any to see where Dracula fits into the larger picture. Turning to social media, I asked people what they thought were some of the more important vampire novels, coming up with an impressive list that had to be really pared down. There's not a lot of surprises on it, but I did find a couple of interesting points: many people believe that Dracula was *the* original Vampire novel, when in fact it's predated by a number of others that in turn influenced Dracula. Stoker's novel proves to be a tipping point, and there's quite a bit of variety after the publication of that book.

I had a gap in the schedule, and it seemed like a good time to start getting ready for October. Somewhere, I decided that I wanted to take a look at a broad swath of a genre, and because I was working on the pieces for October (Dracula), it seemed as good a time as any to see where Dracula fits into the larger picture. Turning to social media, I asked people what they thought were some of the more important vampire novels, coming up with an impressive list that had to be really pared down. There's not a lot of surprises on it, but I did find a couple of interesting points: many people believe that Dracula was *the* original Vampire novel, when in fact it's predated by a number of others that in turn influenced Dracula. Stoker's novel proves to be a tipping point, and there's quite a bit of variety after the publication of that book. My latest post for Kirkus Reviews is now up online. Originally, I'd planned on finishing out the Science Romances with

My latest post for Kirkus Reviews is now up online. Originally, I'd planned on finishing out the Science Romances with  Over on Kirkus Reviews, I have a bit of a roundup post that looks back over the posts that I've written, looking at the foundational stories of the genre, and how they all fit together in the bigger picture. You can read it over

Over on Kirkus Reviews, I have a bit of a roundup post that looks back over the posts that I've written, looking at the foundational stories of the genre, and how they all fit together in the bigger picture. You can read it over

This week on the Kirkus Reviews Blog, I jump ahead from some of the older stories to a very modern author:

This week on the Kirkus Reviews Blog, I jump ahead from some of the older stories to a very modern author:

My latest column for Kirkus Reviews is now online! In it, I talk about Jules Verne and his fantastic novel From the Earth to the Moon. I

My latest column for Kirkus Reviews is now online! In it, I talk about Jules Verne and his fantastic novel From the Earth to the Moon. I  Over on the Kirkus Reviews blog, I've turned my attention to one of my absolute favorite science fiction novels, The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells. One of the absolute greatest works of science fiction, it's a story that I've continually learned more about ever since I first read it so many years ago. You can read

Over on the Kirkus Reviews blog, I've turned my attention to one of my absolute favorite science fiction novels, The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells. One of the absolute greatest works of science fiction, it's a story that I've continually learned more about ever since I first read it so many years ago. You can read