Substance vs. Style in Science Fiction

/Producer Jesse Alexander just wrote up an interesting guest column on website io9 recently, (which you can read here), where he talks about a couple of subjects that I've been thinking about lately: the vast difference between substance and visual appeal of the science fiction genre, particularly in movies.

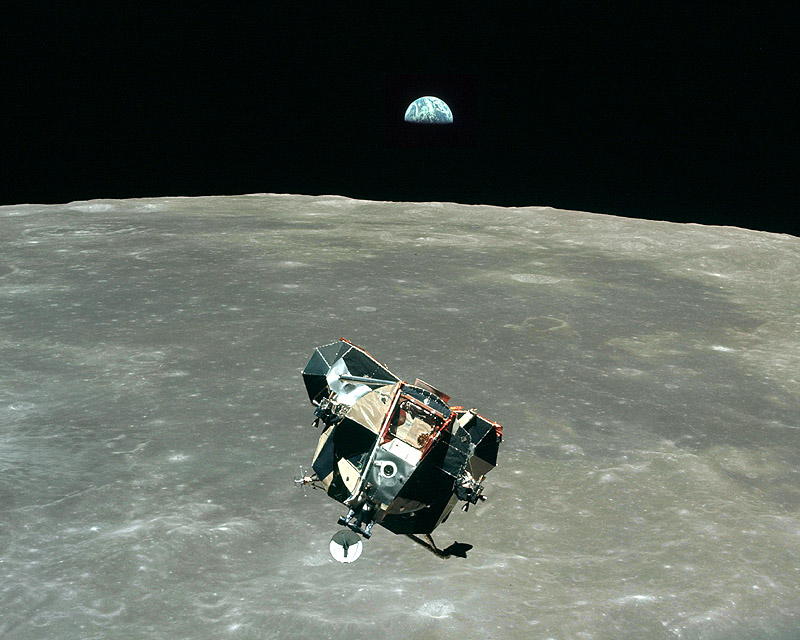

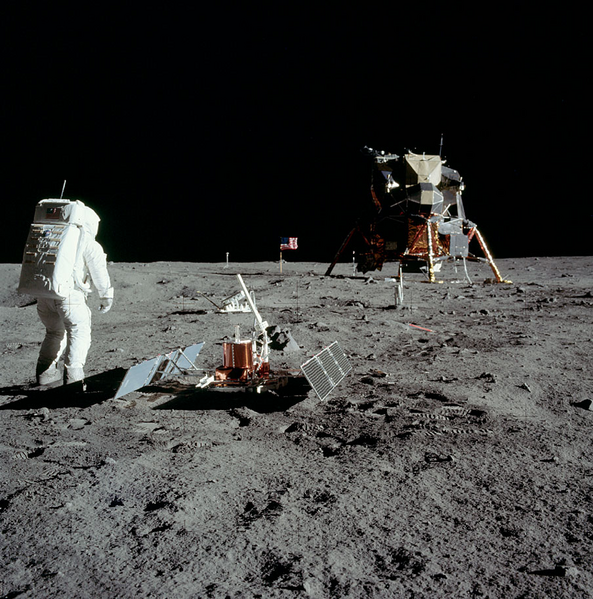

In his piece, he notes that CGI-laden blockbusters have really taken over the movie theaters over the summer season, almost completely. This past summer, we've had Terminator 4, Transformers 2, GI Joe, Star Trek, and Harry Potter all costing in the hundreds of millions of dollars to produce from beginning to end, none of which were really all that great, while the two standout movies in the SF genre were Moon and District 9, both of which cost $5 million and $30 million to create, respectively. This begs the question, as Alexander does, where did these two films succeed where the others failed.

The above films all did really well at the box office, grossing back quite a bit of money (although Terminator: Salvation did pretty poorly, but it will warrant a sequel, if the rumors are to be believed) but of everything that was released this summer, only Moon and District 9 really captured the essence of science fiction on all levels. They were wholly original, influences aside, and are the ones that have come out of this summer that will be remembered for a long time as solid entries in the genre's film side of things.

One of the things that charges are laid against is the use of CGI in films, which has become far more sophisticated and prevalent in films, especially science fiction films. I'm not totally sure that CGI is really the thing to blame here, but the effect that it has on filmmaking and the entire process. CGI is a fantastic tool for filmmakers, especially in the science fiction field. The problem comes when the glamor and expanded visual field overtakes the story in terms of importance.

For me, story is everything with a film or television show, and the Science Fiction genre is a fantastic place for any number of possible stories. There have been a number of fantastic films out there that I can put forward as an example for good storytelling: Minority Report, The Prestige, Serenity, The Fountain, Pan's Labyrinth, and of course, Moon and District 9. These movies utilized special effects throughout, but did so in a way that didn't jeopardize the story to the extent that other films might have. A couple of television shows, such as Battlestar Galactica and Firefly have followed much the same philosophy with their approaches to CGI: the visuals are placed in the film/show to support the events in the story.

My favorite example is 2005's release of Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith and Serenity. Both films with significant fanbases, but with very different approaches to the stories. Serenity was a much smaller film, with a killer story to finish up the Firefly TV series, while Revenge of the Sith was a far more bloated and cumbersome film that cost a significant amount of money to produce. Given the financial troubles and uncertainty of the next couple of years, I would bet that that type of filmmaking will continue, but there will be a rise in films such as Moon, Serenity and District 9. Each of these films received a large amount of critical favor, and while none approached the same amount of money that these larger films pulled in, they didn't cost as much as the much larger films.

One thing about these huge CGI films that I noticed is that the ones this summer were already part of a larger storyline or franchise - there were a lot of numbers after the titles, and I have to wonder if that is part of this empty storytelling trend that Science Fiction seems to have picked up over the past couple decades. I don't mind sequels - There's a number of stories out there that I love seeing more of. But, when does a good franchise become a cash cow, with more of the same to it? Transformers was reportedly like that, even up to the director's level, where more of the same, but just more intense was better. Harry Potter has largely been like this from day one, and Star Trek wasn't all that impressive after you started thinking about it. This, to me, is a sad thing for the genre, one that I've always seen as being far more creative than most of the other genres out there, if only for the exotic subject matter.

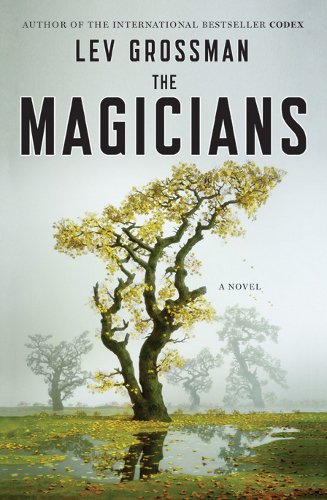

There are a couple of things that bother me about this sort of thing, mainly that people are more than happy to take any sort of mind-numbing entertainment and expect nothing more. While this is a bit of a leap, it seems like this is a problem that extends far beyond the entertainment realm, from education to politics. Moon and District 9 worked brilliantly together this summer because they were two films that had intelligent plots, good characterization and an unconventional way of presenting the stories. Despite that, I read a number of reviews that noted that the plots didn't make sense, that there weren't enough explosions and the like. These sorts of reviews usually bother me, as they did with reviews about Lev Grossman's The Magicians, where people just didn't, or couldn't understand what the stories were about, and because they didn't like them, refused to think any more about the subject.

What I am hoping will come out of this is that smaller, cheaper, genre films will become more popular, with producers who are willing to take a little more of a gamble. The films this summer proved that filmmakers could get around expensive effects, by using models, preexisting locations and actors who might not necessarily be as well known. If there are any lessons to be learned from this summer, it is that when a good story is in place, the film can succeed toe to toe with any of the big blockbusters. For me, I'm happy that there's something out there that's a little different, a bit challenging and above all, something that makes me think about what I'm watching.