The second presentation in the Colby Symposium at Norwich University was titled 'Afghanistan: America's Second Vietnam or its First Victory over Al Qaida?', by Jack Segal. Segal is the Chief Political Advisor to the NATO Joint Force Command Commander, General Wolf Langheld. He is a distinguished figure, having served two tours in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division during the Tet Offensive and again with the 25th Infantry Division, where he earned the Bronze Star and Meritorious Service Medal. Since the war and subsequent education, he's held numerous posts in the US Diplomatic service, playing key roles in the negotiations with the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the US and the USSR, and was named the first US Consul General in central Russia in 1994 and became the Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Lynn Davis in 1995. Following that, he worked with the National Security Council at the White House as the director for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, and worked with the White House's Kosovo group. in 1999, he became the NSA Director for Non-Proliferation, and joined NATO in 2000. He is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the US National Defense University. To say that he's had a distinguished and important role in foreign affairs is a bit of an understatement.

The second presentation in the Colby Symposium at Norwich University was titled 'Afghanistan: America's Second Vietnam or its First Victory over Al Qaida?', by Jack Segal. Segal is the Chief Political Advisor to the NATO Joint Force Command Commander, General Wolf Langheld. He is a distinguished figure, having served two tours in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division during the Tet Offensive and again with the 25th Infantry Division, where he earned the Bronze Star and Meritorious Service Medal. Since the war and subsequent education, he's held numerous posts in the US Diplomatic service, playing key roles in the negotiations with the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the US and the USSR, and was named the first US Consul General in central Russia in 1994 and became the Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Lynn Davis in 1995. Following that, he worked with the National Security Council at the White House as the director for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, and worked with the White House's Kosovo group. in 1999, he became the NSA Director for Non-Proliferation, and joined NATO in 2000. He is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the US National Defense University. To say that he's had a distinguished and important role in foreign affairs is a bit of an understatement.

His talk looked to the history of Afghanistan, and the roots of the conflict that we are currently in. He opened with a couple of comments about the present affairs: he noted that he always asks soldiers that he meets a question that his father asked him while he served in Vietnam: "Are you making any headway?". When his father asked him in the 1960s, he said that he had sat on the question for a month while he tried to figure out the answer. He said that he's gotten a variety of responses from soldiers currently serving in Afghanistan. The war is complicated, he noted, politically, and geographically. One question he's fielded from politicians is that the Afghanistan border needs to be secured, to which he's replied that it's the equivalent of attempting to seal the US Border from Maine to Key West: it's a lot easier said than done.

Segal then turned to history, starting with the Buddha statues that had recently been destroyed by the Taliban, speaking to a long, troubled history with religious connotations. The statues were destroyed because they went against some of the tenents of Islam: deities aren't permitted to be represented in human form. It was an interesting example as to the lengths to which they will go to protect their faith.

Afghanistan was once part of the 'Great Game', between Persia, Russia and the United Kingdom, who went and divided up the country amongst themselves. The UK had extensive colonial interests in India, and were worried about the Russian ambitions in the region. In 1839, the first Anglo-Afghan war began at Ghazni, and while it had begun in favor of the British, by 1842, the entire British army, save for a single person, was massacred at the Khyber Pass. The UK attempted to invade twice more, with similar results, before the region was divided up politically by the major powers in the region, resulting in instability in the future. [As an aside, a good book on the British experiences in India and Afghanistan is Saul David's 'Victoria's Wars'.] The British relinquished control on August 19th, 1919. For part of the 20th century, the country went through several rulers, who made great changes in the nation, working to bring it out of isolation. The monarchy was abolished in 1973, and Afghanistan was declared a Republic.

Segal talked extensively about the Soviet invasion of 1979. On December 24th, the Soviet military deployed a large ground, air and special forces mission in the country, and installed their own Soviet-friendly leader. Thousands of people were killed under this regime. Over the next ten years, a million Afghans were killed, another 1 million internally displaced, and a further 3 million refugees. It was a major disruption to the country. The Soviet Union played out their interactions as a protection from the Mujahedeen, and sought to remove Islamist ties with the country, preferring their own atheistic model - an easy sell to the USSR. This created opportunity for enemies of the USSR: A good example is the events of Charlie Wilson's War, as the US began to funnel money and weapons into the country. At the start of the invasion, the US handed over around $1 million. By the end of the occupation 10 years later, that money ballooned to over a billion dollars.

During this time, Osama Bin Laden enters the picture in Afghanistan to help oppose the Soviet occupation and agenda: he attempted to create a holy war to kick them out. At the same time, Stinger missiles were introduced to help counter the tactical advantages that the Soviets had with their helicopters. They were wiped out, and soon, weren't able to fly. By 1989, over 16,000 Soviet soldiers were killed, a lot more wounded, and following the Soviet withdrawal, Afghanistan's Soviet placed leader, Najibullah, remained for three years before the country dissolved into Civil War, which lasted until 1996, when the Taliban game into power.

Segal pointed out that Taliban is a plural term: the singular is Talib, which essentially means 'Student of Islam'. He noted that when we say that we're fighting 'The Taliban', it comes across that we're fighting the students of Islam, a mistake that has further molded their expectations of what we intend to do in the country. Around this same time, Osama Bin Laden has returned to the country with Al Qaida, after his citizenship was revoked by Saudi Arabia and he was kicked out of Sudan. He was welcomed by the Taliban government, and he began to set up training camps, training about a thousand people a month.

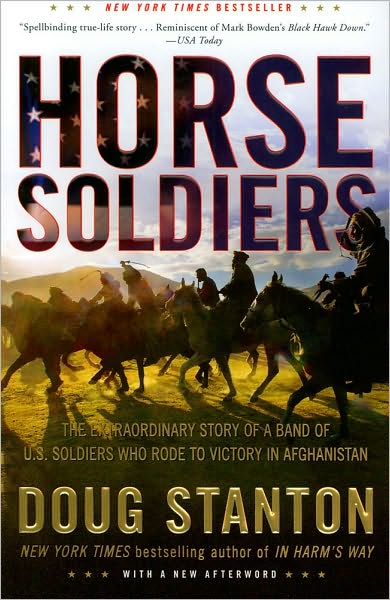

In 2001, he helped to orchestrate the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and US response was swift, with an invasion of Afghanistan by US Special Forces. (A note, Doug Stanton, who also presented at this Symposium, talked extensively about this) By 2004, the warlords were back in control of the country, but Taliban rule has resisted between 2002 and 2006. As of 2009, a number of new players have entered the field: businesses, criminal groups, religious groups, and so forth, resulting in a splintered country. Now retired General Stanley McCrystal issued a report in 2009, stating that the situation in Afghanistan was serious, under resourced and deteriorating. A major change in strategy would be needed to turn the war around. He proposed a population centric, regional strategy, although he and Karl Eikenberry were split on what to do. As of right now, 132,000 soldiers are in Afghanistan, while there's only around 100 Al Qaida in the country.

Segal noted that there are significant problems, and a disconnect in the nation's strategy towards the country. The original mission was to disrupt the operations of Al Qaida, not the Taliban, and that two concurrent strategies, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency don't necessarily work as well together at points.

He also told the group that the situation on the ground is incredibly complex, with a network of tribes, sub tribes and conflict between other groups throughout the country. There were situations where interpreters working on behalf of the US were from an enemy tribe during sensitive interactions, causing problems. Networking, Segal said, is important, and understanding the networks and the people is vital to the success of the Afghanistan mission. He noted that we're doing good things right now: building roads, and bridges, as well as a police and military force. However, money is becoming a problem, with the costs up to around $600 million a day.

A key element to understand in the country is that Islam plays a key role in how people live their lives. In 33 out of the 34 provinces in the country, the Taliban maintain a shadow government, and are able to provide what the people want: security, and adjudication of civil disputes: they are legitimate in the eyes of a lot of people, because it is so closely linked to their beliefs. Segal said early in the talk that the thing that he learned the most was how people in the 14th century lived: the mindset it similar, because of the extreme isolation of the country. At points, US troops were asked if they were Russian, because villagers simply didn't realize that the USSR had left.

This, coupled with a lack of clarity as to what the US is working to achieve, cause problems when working to conduct a war and to justify the costs and sacrifices in the country. When asked what the conditions of victory were, he simply stated that there was no victory: just success, a self-sufficient government that could stand on its own. This brings up some issues, especially when it's realized that neither side is willing to budge or compromise on their values: the subject of women’s rights is a particularly tough one, given how ingrained some of the beliefs are in the country: the people who believe what we believe exist, but aren't in the majority.

At the end of the day, Afghanistan is a country that has proved formidable throughout its history: both the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union were driven out after long, grueling wars with high numbers of casualties. While the US doesn't have to follow this same path, there's a number of things that need to be understood about the country's history, to avoid some of the things that caused problems before.

The first is to understand the complexity of the situation on the ground, and the extensive networks and social structure in Afghanistan. Uniting the country is difficult at best, with a plethora of rivalries and grudges from group to group. Along the same lines, it's important to understand and to not underestimate the importance of Islam in the culture. The Taliban are seen as legitimate because it is very similar to what the people believe, and that the Taliban is able to provide what they want in a government: security and social adjudication. These elements need to be included, because both sides seem to be unable and unwilling to change or compromise their beliefs.

The second element to understand is the mission itself: originally, it was to disrupt Al Qaida, and to prevent them from carrying out threats against the United States: however, with a ratio of over a thousand to one, this mission seems to require rethinking. When Segal asks soldiers what headway they've made, the answer is unclear, because people involved are unclear as to the mission and the overall objectives in the country: if it's to root out Al Qaida, that's one thing, but complete and utter nation building is another mission altogether, especially when one considers the complications involved with the current conflict in Libya, and the one winding down in Iraq.

The future is unclear for Afghanistan, and it will depend greatly upon the the changes in stance, strategy and attitude towards the ongoing operations in the country.

This past weekend while at ReaderCon, I finally completed George R.R. Martin's first novel in his Song of Ice and Fire series, A Game of Thrones, something I've been trying to do since I first bought the book in 2007. Epic fantasy doesn't do much for me: I'm annoyed at the sheer complexity of most of the stories, (most of it unnecessarily so) and while that's put me off from Martin's books for a long time, I'm coming to understand some key differences between his books and the others that I've often read. At the same time, I've been following along with the HBO adaptation of A Game of Thrones, which helped me visualize which characters were which, along with the various storylines.

This past weekend while at ReaderCon, I finally completed George R.R. Martin's first novel in his Song of Ice and Fire series, A Game of Thrones, something I've been trying to do since I first bought the book in 2007. Epic fantasy doesn't do much for me: I'm annoyed at the sheer complexity of most of the stories, (most of it unnecessarily so) and while that's put me off from Martin's books for a long time, I'm coming to understand some key differences between his books and the others that I've often read. At the same time, I've been following along with the HBO adaptation of A Game of Thrones, which helped me visualize which characters were which, along with the various storylines.

This morning, I pulled out of my driveway and angled down U.S. Route 2, shifting onto VT Route 12 and through the hills of Berlin and Northfield to work. Tonight, I’ll likely make my way back on the same route, but I very well might take I-89N up from Northfield to Berlin. Never once, in any of the hundreds of trips that I’ve made along that route, have I ever seriously wondered where the roads came from. They’ve always been there, for better or for worse, and they make up the foundation upon which our modern lives exist. Earl Swift’s latest book, The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways, is a grand story that I’ve long wanted to read about: the development of the American highway and interstate system.

This morning, I pulled out of my driveway and angled down U.S. Route 2, shifting onto VT Route 12 and through the hills of Berlin and Northfield to work. Tonight, I’ll likely make my way back on the same route, but I very well might take I-89N up from Northfield to Berlin. Never once, in any of the hundreds of trips that I’ve made along that route, have I ever seriously wondered where the roads came from. They’ve always been there, for better or for worse, and they make up the foundation upon which our modern lives exist. Earl Swift’s latest book, The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways, is a grand story that I’ve long wanted to read about: the development of the American highway and interstate system. This year has seen several novels that I've come to with high expectations, only to be let down by a poor story, characters and writing. M.M. Buckner's latest novel, The Gravity Pilot, falls into this trend. Despite a strong premise and interesting world, the book is a lack-luster read, one that left me frustrated and awaiting for the final chapters.

This year has seen several novels that I've come to with high expectations, only to be let down by a poor story, characters and writing. M.M. Buckner's latest novel, The Gravity Pilot, falls into this trend. Despite a strong premise and interesting world, the book is a lack-luster read, one that left me frustrated and awaiting for the final chapters.

China Miéville has been on a bit of a tear to explore every genre through his books. With Embassytown, he turns from his earthbound adventures of late (The City and The City and Kraken), and goes into deep space, for a truly alien world.

China Miéville has been on a bit of a tear to explore every genre through his books. With Embassytown, he turns from his earthbound adventures of late (The City and The City and Kraken), and goes into deep space, for a truly alien world.

On the airplane over to Europe, I was a bit puzzled by the screening of X-Men 3: The Last Stand, but because I couldn't sleep, I watched it, and remembered just how bad it was. Where the first two X-Men films were fun, and fairly well done, the third felt rushed, overcooked, with no cohesive storyline, characters and action that didn't make sense, but with some definite promise to it. It's unfortunate that it was such a train wreck, and it put me off from the follow-up Wolverine film, which I've still not seen. Thus, the news that there was another X-Men film coming out simply didn't register, until it became fairly clear that this was going to be a film that was somewhat different.

On the airplane over to Europe, I was a bit puzzled by the screening of X-Men 3: The Last Stand, but because I couldn't sleep, I watched it, and remembered just how bad it was. Where the first two X-Men films were fun, and fairly well done, the third felt rushed, overcooked, with no cohesive storyline, characters and action that didn't make sense, but with some definite promise to it. It's unfortunate that it was such a train wreck, and it put me off from the follow-up Wolverine film, which I've still not seen. Thus, the news that there was another X-Men film coming out simply didn't register, until it became fairly clear that this was going to be a film that was somewhat different.

Historian Dr. Michael Robinson, of the University of Hartford, opened his talk with a William Falkner quote that helped frame the

Historian Dr. Michael Robinson, of the University of Hartford, opened his talk with a William Falkner quote that helped frame the

I vividly remember the events of September 11th. I was at my high school’s library, on one of the computers when I came across the news on a news site, and over the course of the afternoon, we learned that it was no accident, but a deliberate attack against the country. I remember being concerned that we didn’t know who did it, until the news began to shift over the next couple of days to the Middle East. In my 10th grade history class, we listened to the radio. The road was dead silent as the commentators spoke about the event. That day has defined the existence of my generation, in every single facet of life, as we’ve watched the towers tumble into two wars across the world, while our domestic society has undergone major shifts and changes that we’ve gone along with in the name of security and safety. One man changed the world, and he’s now dead.

I vividly remember the events of September 11th. I was at my high school’s library, on one of the computers when I came across the news on a news site, and over the course of the afternoon, we learned that it was no accident, but a deliberate attack against the country. I remember being concerned that we didn’t know who did it, until the news began to shift over the next couple of days to the Middle East. In my 10th grade history class, we listened to the radio. The road was dead silent as the commentators spoke about the event. That day has defined the existence of my generation, in every single facet of life, as we’ve watched the towers tumble into two wars across the world, while our domestic society has undergone major shifts and changes that we’ve gone along with in the name of security and safety. One man changed the world, and he’s now dead. In Will McIntosh's debut novel, Soft Apocalypse, the world as we know it ends with a whimper, not a bang. The end of America and the rest of the world comes out of our over indulgence, use of resources and all of the problems in society reaching a dull roar that tears down the world as we know it. This story takes a small cast of characters and looks at them over a much longer point of time than more novels, providing a unique perspective on what the future might hold.

In Will McIntosh's debut novel, Soft Apocalypse, the world as we know it ends with a whimper, not a bang. The end of America and the rest of the world comes out of our over indulgence, use of resources and all of the problems in society reaching a dull roar that tears down the world as we know it. This story takes a small cast of characters and looks at them over a much longer point of time than more novels, providing a unique perspective on what the future might hold.

Each year, the Colby Symposium awards the Colby Award to a first notable book from an author that deals fundamentally with the nature of warfare and contributes substantially to the field. During the awards dinner this year, executive director and Norwich University Alum, Carlo D'Este said that it was rare that the entire committee universally agrees on a single book, but that this was the case for the 2011 prize, going to Karl Marlantes, with his first acclaimed novel, Matterhorn.

Each year, the Colby Symposium awards the Colby Award to a first notable book from an author that deals fundamentally with the nature of warfare and contributes substantially to the field. During the awards dinner this year, executive director and Norwich University Alum, Carlo D'Este said that it was rare that the entire committee universally agrees on a single book, but that this was the case for the 2011 prize, going to Karl Marlantes, with his first acclaimed novel, Matterhorn. The third talk of the Colby Symposium featured author Doug Stanton, author of the widely acclaimed New York Times bestseller

The third talk of the Colby Symposium featured author Doug Stanton, author of the widely acclaimed New York Times bestseller  The second presentation in the Colby Symposium at Norwich University was titled 'Afghanistan: America's Second Vietnam or its First Victory over Al Qaida?', by Jack Segal. Segal is the Chief Political Advisor to the NATO Joint Force Command Commander, General Wolf Langheld. He is a distinguished figure, having served two tours in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division during the Tet Offensive and again with the 25th Infantry Division, where he earned the Bronze Star and Meritorious Service Medal. Since the war and subsequent education, he's held numerous posts in the US Diplomatic service, playing key roles in the negotiations with the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the US and the USSR, and was named the first US Consul General in central Russia in 1994 and became the Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Lynn Davis in 1995. Following that, he worked with the National Security Council at the White House as the director for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, and worked with the White House's Kosovo group. in 1999, he became the NSA Director for Non-Proliferation, and joined NATO in 2000. He is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the US National Defense University. To say that he's had a distinguished and important role in foreign affairs is a bit of an understatement.

The second presentation in the Colby Symposium at Norwich University was titled 'Afghanistan: America's Second Vietnam or its First Victory over Al Qaida?', by Jack Segal. Segal is the Chief Political Advisor to the NATO Joint Force Command Commander, General Wolf Langheld. He is a distinguished figure, having served two tours in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division during the Tet Offensive and again with the 25th Infantry Division, where he earned the Bronze Star and Meritorious Service Medal. Since the war and subsequent education, he's held numerous posts in the US Diplomatic service, playing key roles in the negotiations with the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks between the US and the USSR, and was named the first US Consul General in central Russia in 1994 and became the Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Lynn Davis in 1995. Following that, he worked with the National Security Council at the White House as the director for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, and worked with the White House's Kosovo group. in 1999, he became the NSA Director for Non-Proliferation, and joined NATO in 2000. He is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the US National Defense University. To say that he's had a distinguished and important role in foreign affairs is a bit of an understatement.

Climate change is here to stay. It’s a bit of a foregone conclusion at this point, given the rise of human industrialized society and the scientific evidence that is increasingly supporting the idea that we’ve influenced how we have changed our climate to the point where it’ll cause problems for life as we know it. As such, it’s a little surprising that there isn’t more of an impact in the science fiction realm. I think that’s about to change, as that reality sinks in a little more, and it seems that there are a growing number of books that are starting to come out about the topic, which I’m rather happy about. In 2009, Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Windup Girl was released to great acclaim, set in a post-oil world, and is something of a novel that demonstrated what type of story really works.

Climate change is here to stay. It’s a bit of a foregone conclusion at this point, given the rise of human industrialized society and the scientific evidence that is increasingly supporting the idea that we’ve influenced how we have changed our climate to the point where it’ll cause problems for life as we know it. As such, it’s a little surprising that there isn’t more of an impact in the science fiction realm. I think that’s about to change, as that reality sinks in a little more, and it seems that there are a growing number of books that are starting to come out about the topic, which I’m rather happy about. In 2009, Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Windup Girl was released to great acclaim, set in a post-oil world, and is something of a novel that demonstrated what type of story really works.