Prometheus has Landed

/ Ridley Scott's addition to the Alien franchise has finally hit theaters following a fantastic marketing blitz. Prometheus is a good, but at points flawed, predecessor to his own 1979 start to the franchise. One of my more anticipated films of the year, I found it to be a decent film, living up to my somewhat lowered expectations, and certainly one that I'll watch again.

Ridley Scott's addition to the Alien franchise has finally hit theaters following a fantastic marketing blitz. Prometheus is a good, but at points flawed, predecessor to his own 1979 start to the franchise. One of my more anticipated films of the year, I found it to be a decent film, living up to my somewhat lowered expectations, and certainly one that I'll watch again.

Prometheus follows a lot of similar formula as that of Aliens, with some notable differences. An archeological team comes up with a series of star maps that points the team to a distant world with extraterrestrial life. An interstellar expedition is assembled and financed, and sent off to a moon designated LV-223 in a far off system. Overseen by a robot overseer on the 200 day trip, the crew lands on the moon, and discover an unnatural feature. Suiting up, the scientific contingent set off to find what message might have been left behind. Helmets come off, people get lost and suddenly, chaos ensues as the relics infect the crew.

The key to enjoying Prometheus seems to be ignoring that the film is connected to the Alien universe. While it's not as good as Alien, I did enjoy it a bit more than Aliens, and when compared to your average summer blockbuster, Prometheus comes off rather well.

What's notable for Prometheus is how absolutely gorgeous it is: the design of the world is one of the best that I've seen, a spaceship that looks practical and well-rooted in the modern world, much as the Nostromo likely felt back when it was first released. Outside of the ship, the film is treated to a phenomenal opening credit scene, and continues to put together some wonderful planetscapes and general images. It's a slick, great movie, visually. Even the 3D, which I normally can't stand, worked exceptionally well throughout the film - there were none of the flat sections where the film reverts back to 2D outside of the action sequences. Here, it's seamlessly in the background, where it's never intrusive.

Prometheus's story is where the film begins to stumble, while also attempting some very ambitious things. There's a lot that Scott's tried to pack into the movie, ranging from overarching themes of science verses faith, the idea of maker-gods who have helped along the human race, to the responsibilities of science and technology. It's easy to see where the ideas are, and where they're attempting to go, but it's lost in a bit of a muddle. While watching the film, I got the distinct impression that there was quite a bit cut out of the movie to keep the run time under a certain level, and I can't help but wonder if somewhere down the road, we'll get the bits that were cut out, which will hopefully help to reinforce some of the characters and overarching themes.

Beyond that, some of the letdowns come with some of the really stupid things that the characters do throughout the movie. Characters take their helmets off at every point, even when it seems like it might be a really bad idea, quarantine protocols are ignored, and everything that should be done to keep a trillion dollar mission on schedule and safe really isn't done. This is where Prometheus is a disappointment: there's a lot of potential that's lost in the characters and their actions.

The characters frequently have their moments to shine: Charlize Theron does a fantastic job as Meredith Vickers, the Weyland Corporation rep, while Noomi Rapace's Elizabeth Shaw finally finds her legs towards the end of the film, after she's been pushed to the brink. Most notable, however, is David, portrayed by Michael Fassbender, the ship's robot who has some considerable issues when it comes to his maker, Peter Weyland. Frequently though, each of the characters are drawn with too broad a brush and the often come off poorly. Other characters, like Captain Janek and the bridge crew, have great appearances - Benedict Wong especially, but just little enough to make us want more.

Where the story really does work is looking at the big ideas, and I applaud the film for really trying something, rather than simply mirroring the audience's expectations. The idea of an alien race bringing their technology to seed a world, only to find that they've made a mistake is a rather epic idea, and I'm thrilled to see the ideas there: I simply wish that they'd been followed up on a bit more. The ideas of religion and science that come out of those ideas are similarly brought up, and not fully explored. While that's not great, I can't really think of the last major science fiction movie that put together interesting ideas with a dramatic story, (Maybe Inception?) and I'm happy to see a film at least try to do something a bit different.

Weirdly, this film felt very optimistic throughout: focusing on exploring and learning about our surroundings, it's an interesting change from many of the reactionary (and still excellent) science fiction out there, even up through the end. Where Alien was purely a horror film set in space, Prometheus feels more like a space opera film, with quite a few horror elements.

Looking back, the film is stymied by its lack of focus: there's several subplots, focusing on David/Weyland, the Engineers, and corporate intentions, all of which try to share the space with each other. The film never quite meshes in the way that it should have, and coupled with the extraordinarily high expectations set forth by the film's marketing contingent; it's no wonder that the film has received such mixed reviews. In a lot of ways, the film would have likely fared better if its connections to Alien had been completely severed, with it released as a stand-alone science fiction adventure. Here lies the major problem when attempting to bring back a well-worn franchise with an established fanbase: it's almost impossible to capture what everybody loved about it, and entrenched expectations really prevent the filmmakers from really innovating. Prometheus is able to get away from this a bit: I'm sure that continuity hounds and nitpickers will argue for a long time about this, but Scott really is able to pull out a good movie out for his return to the genre.

But, despite all of the issues with the film, I really enjoyed it. I'm a sucker for great imagery in the genre, and Prometheus certainly delivers here. But beyond that is a film that, once some of the extra baggage is ignored, is a decent film when you look at it against the lesser Alien films, or even the broad canon of summertime blockbusters. It doesn't quite stack up as high as Blade Runner and Alien do in the greater picture, but it's a good film that should have been great. I can live with that.

Over on the Kirkus Reviews Blog, I've written up a short sketch of Ray Bradbury's life,

Over on the Kirkus Reviews Blog, I've written up a short sketch of Ray Bradbury's life,

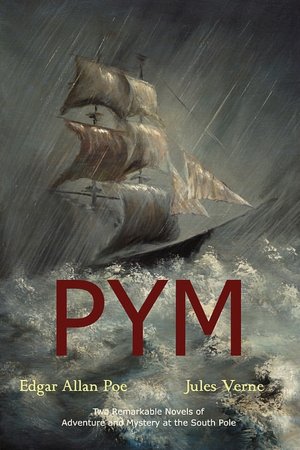

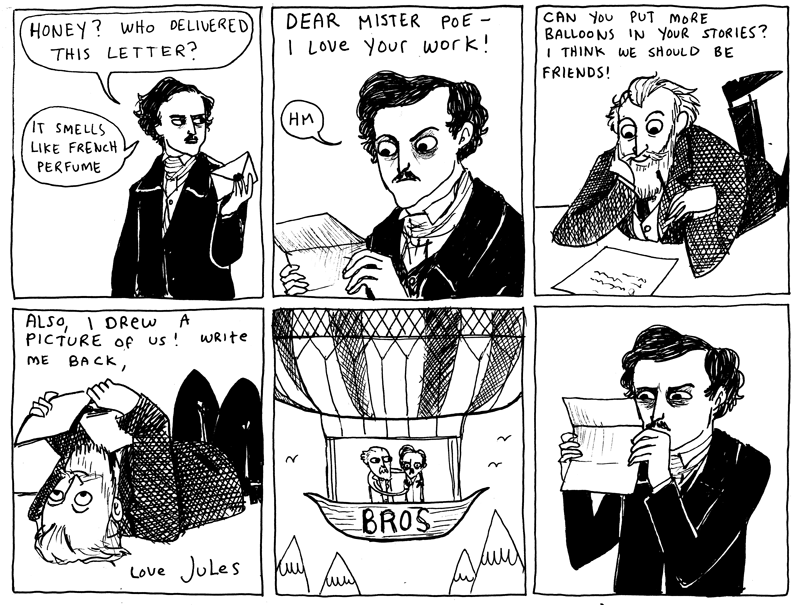

My latest column for Kirkus reviews has just been posted! While doing some reading on Edgar Allan Poe, I came across an interesting point: Poe only wrote a single novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, which was later picked up upon by legendary science fiction author, Jules Verne in An Antarctic Mystery. In a large way, it was one of the first works of fan fiction!

My latest column for Kirkus reviews has just been posted! While doing some reading on Edgar Allan Poe, I came across an interesting point: Poe only wrote a single novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, which was later picked up upon by legendary science fiction author, Jules Verne in An Antarctic Mystery. In a large way, it was one of the first works of fan fiction!

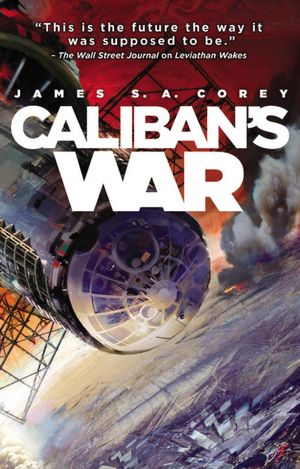

Caliban's War, James S.A. Corey's follow-up to the Hugo-nominated Leviathan Wakes takes readers back to the well-realized world of The Expanse. It's an all guns blazing thrill-ride that ups the stakes in the Expanse and keeps me wanting more.

Caliban's War, James S.A. Corey's follow-up to the Hugo-nominated Leviathan Wakes takes readers back to the well-realized world of The Expanse. It's an all guns blazing thrill-ride that ups the stakes in the Expanse and keeps me wanting more.

This past weekend, the Hugo award nominations were announced, with some great things on the ballot. The full list can be found

This past weekend, the Hugo award nominations were announced, with some great things on the ballot. The full list can be found

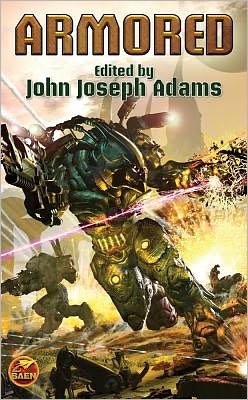

Tomorrow, John Joseph Adam's latest original anthology, Armored, hits stores. I'm pretty excited for this one, because I've read most of it already. Last year, the book was announced, and I got to help out a bit with some of the behind the scenes work in getting the book up and running: slush reading, some recommendations, and thoughts that I had about the stories that I read.

Tomorrow, John Joseph Adam's latest original anthology, Armored, hits stores. I'm pretty excited for this one, because I've read most of it already. Last year, the book was announced, and I got to help out a bit with some of the behind the scenes work in getting the book up and running: slush reading, some recommendations, and thoughts that I had about the stories that I read. I've sold a new article to the Norwich Record, titled Out of the Ashes: How an Irish Episcopal Priest Saved Norwich University. This was one of the projects that I was working on last fall, and shortly after the start of the New Year, I submitted my final draft. The research phase was interesting: going through archives and piecing together a rather interesting and diverse man that was a central, but forgotten figure in Norwich University and local Vermont history.

I've sold a new article to the Norwich Record, titled Out of the Ashes: How an Irish Episcopal Priest Saved Norwich University. This was one of the projects that I was working on last fall, and shortly after the start of the New Year, I submitted my final draft. The research phase was interesting: going through archives and piecing together a rather interesting and diverse man that was a central, but forgotten figure in Norwich University and local Vermont history.

This past weekend was Boskone 49, a science fiction / fantasy literature convention down in South Boston. After great experiences at ReaderCon the past couple of years, I decided to head down and partake in the fun for the spring, hitting up a bunch of panels and getting to meet up with people that I've largely talked to online over the past couple of years.

This past weekend was Boskone 49, a science fiction / fantasy literature convention down in South Boston. After great experiences at ReaderCon the past couple of years, I decided to head down and partake in the fun for the spring, hitting up a bunch of panels and getting to meet up with people that I've largely talked to online over the past couple of years. Every year, the 501st Legion goes to the polls to elect new leadership for the group. This year, my friend Mike Brunco and I decided that we were going to run for the leadership roles, with Mike taking on the Commanding Officer position, and with me taking on the Executive Officer post.

Every year, the 501st Legion goes to the polls to elect new leadership for the group. This year, my friend Mike Brunco and I decided that we were going to run for the leadership roles, with Mike taking on the Commanding Officer position, and with me taking on the Executive Officer post.

During a campaign stop in Florida in advance of the next Republican Primary, former speaker of the house Newt Gingrich

During a campaign stop in Florida in advance of the next Republican Primary, former speaker of the house Newt Gingrich