So, the iPad?

/

The Borders Blog for Science Fiction and Fantasy had a post up around wanting to split up Science Fiction and Fantasy stories. It's an interesting discussion, but it misses a lot on the mark about the types of stories that are around in the genre, while also completely missing the entire point about genres in the first place (which makes this really funny for a major bookstore blog), which is to say that genres are purely a marketing tool that are designed to put a certain product into a clearly defined audience: the speculative fiction fan.

Books in a bookstore are marketed based on the elements of the story, and are essentially grouped together based on what the characters experience, rather than the story type. Thus, bookstores are all predicable marketed as Mystery, Speculative Fiction (which is a horrible term that pretty much encompasses... everything in fiction, but really stands for Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror novels), Romance, Literature (upper tier fiction / classics), sometimes Christian Fiction, sometimes poetry (although that's sometimes lumped into classics), sometimes Westerns, and then all the various nonfiction categories, which are arrayed by topic. Beyond the marketing element, genres are essentially meaningless constructions that should have no impact on the reading of the book.

There is not a whole lot that separates the two genres from one another, which makes this argument somewhat confusing. Splitting Science Fiction and Fantasy apart simply because there's a perceived, and false, notion that science fiction authors hate fantasy, is a ridiculous notion, because it's overly simplistic and not something that I think has any bearing on the actual books in the respective genres. From every author that I've ever read, spoken to, or listened to, there is an understanding that fiction is primarily about storytelling and the characters within said stories. Very few authors, I think, will set out specifically to write a book because it will fall within the science fiction genre. They might have a good story that falls specifically within the science fiction or fantasy genre, however, and the distinction is that the stories and the genres themselves aren't uniform blocks of good and bad. It's a pretty shortsighted statement to say that you hate a genre as a whole, simply because it has magic or other fantastic elements in it, or for any other reason. Looking at other genres, it's highly unlikely that you'll find a unified block of writers that like or dislike any other genre within the general fiction heading, and undoubtedly, you will find various groups of authors and fans that dislike certain subgenres within the larger genres.

This past weekend, I attended ReaderCon, and attended a panel around interstitial fiction, which primarily defines the stories that fall within the genres. It was an interesting talk, and largely boiled down to: there are simply some stories that are indefinable, because the stories have elements that move between both genres. There are major, general trends within science fiction and fantasy, especially concerning their outlook on the world, but these are not universal, and ultimately, the definition simply defines where the book is placed in a bookstore. One panel member at the con, Peter Dube, noted: “If there is no pleasure in the text, I won’t read it.”

At the end of the day, it is those two things that define the genre: the buyer, and the bookseller. In general science fiction, fantasy, weird fiction, horror and gothic fiction and all of the others generally appeals to a similar audience, and thus, everything is marketed together, which helps both the buyer and the bookseller get what they want: a good read, and a sale.

This past weekend was consumed with a convention called ReaderCon, which was hosted down in Burlington, MA. As a member of the 501st, I've attended several different types of conventions before, but out of all of them, I think that this convention was one of the best ones that I've ever gone to, and already am looking around for comparable ones to attend. Far from the costuming and media cons that I've visited in the past, ReaderCon lives up to its namesake: it's all about speculative fiction literature.

Never was this more apparent when I arrived on Friday morning and picked up my badge. Patrons in the lobby were engrossed in books, reading away, waiting for the first day's events to start. There was quite a few panels and discussions throughout the weekend, and I was particularly interested in a select number of these, for the content of the panel, but also because of some of the people that were attending: Blake Charlton, Paolo Bacigalupi, Allen M. Steele, Samuel Delany, Charles Stross, Elizabeth Hand, Brett Cox (My Gothic Lit professor) and Nora Jeminsin, just to name a couple. The entire participants list numbered over two hundred people, but those names were ones that I had particular interest in meeting, as I've read all of their books.

Over the course of the weekend, I attended a number of panels: New England: At Home to the Unheimlich, about the propensity of horror writers to be influenced by the region, Influence as Contagion, about films and expectations, Citizens of the World, Citizens of the Universe, Global Warming and Science Fiction, about new directions for the genre to take, New And Improved Future of Magazines, Folklore and its Discontents, Science for Tomorrow's Fiction, How I Wrote The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, and How to Write for a Living, to speak nothing of the hours that I spent in the bookstore looking over what was for sale, and carting away my own, large, expensive pile of books.

The highlight though, was getting to meet a couple of authors whom I've befriended or talked to as I've worked for SF Signal and io9 over the past year or so, Blake Charlton, Paolo Bacigalupi and Nora Jeminsin. These three authors were ones who have just delivered their first novels, recieving quite a bit of acclaim (Bacigalupi has already received the Nebula award, the Compton Crook and Locus awards for Best First Novel, and apparently, is on the short list for the John Campbell Award for his book The Windup Girl) Meeting these guys was just amazing, because not only did they sign my books, I got to talk to them extensively about their books and science fiction, and generally have a good time. Along the way, I also met SF/F author David Forbes, whose book I picked up at the conference, as well as geek musician John Anealio, whom I've talked to online (I was on his podcast at one point) and who's music I really like.

This convention seemed to be much in line with what the science fiction scene seemed to be back in the 1970s when there wasn't much beyond the literature scene for science fiction and fantasy materials. That's largely changed with the introduction of blockbusters, with major Comic Cons springing up all over the place, which get a little tiring beyond the autographs and vendor tables. ReaderCon offered a stimulating experience for me, with a number of panels and opportunities that really got me thinking and interacting with a lot of other fans of the genre.

After six years, Lost has finally come to an end. What started out as a surprising beginning, ABC's surprise hit was a show that defied tradition, genre and storytelling to create what is possibly one of the better television shows to have ever been released. After a hundred and twenty one episodes, the show has long remained a favorite, even when it was having its off moments, because of the detailed storytelling, characters and references within the show. Lost is a novel, simply put, and no singular part really takes away from that as a whole. Because of this, the lackluster finale that finished off the show really doesn't ruin anything for me.

Since the beginning of the show, when Jack awakens in a field, it's been fairly clear that there's quite a bit more to this show than most others out there. The large ensemble cast, the strange events and discoveries and obscure references to mythology, literature, religion and free thought have grown significantly over the drama's run on television. One moment stood out for me in the first season, when John Locke, teaches Walt how to play backgammon, holding up a white and a black stone.

This has long been a cornerstone of the show, opposites, balance, good vs. evil and chaos vs. order, and it has been embodied in a number of different elements throughout the show, in the personalities of the characters, the actions that they take, and the events that have occurred on the island. Within this larger theme and storyline, the survivors of Oceanic 815 wage their own stories and struggles, which in turn fits into the story of the island, and all that it embodies. Lost is a very literary show, one that is both intelligent and well structured, only hampered in its execution.

The finale, The End, was underwhelming at best. There was no great reveal that helped to tie up storylines, and nothing that fundamentally changed the characters beyond what had happened in the show already. Essentially, the last two hours was the combined momentum from the show coming to a halt. While this was to be expected, it did so in a lackluster and uninspiring way. Throughout the show, a conflict has arisen between Jack Shepherd and John Locke, who respectively represented empirical science over emotional religion (or something similar), with an eye towards logic over chaos and presumably, good over evil. There has been some absolutely terrific storytelling, and a very cool reversal of roles between the two characters over the course of the season. While an ultimate conflict was building over the entire show, the end, with a quick fight, and with Locke being shot in the back by Kate Austen, there was little significance or even forward movement for any of the characters.

Furthermore, a big answer for one of the more pertinent questions regarding the nature of the island was discovered much earlier on, when Jacob explained that the island was essentially a cork, holding back a great evil, and his job, as a gatekeeper, helped keep the world in balance. Indeed, the visual symbolism between he and his brother is marked by the clothing that they wear, and the personalities that they have, which mirrors what Jack and Locke exhibit. In a very cool way, the characters fill roles that are much larger than themselves, fitting into fates that are beyond their control, and with plenty of literary significance to have continued discussion over for years to come.

What the finale did do was put a couple of the show’s elements at odds with one another. On one hand, it becomes clear that the story is somewhat preordained, that everybody will end up where they end up because of an afterlife or fate, or some invisible hand, while on the other hand, the show is one that is largely driven by the actions that the characters take throughout the show, which allows for one side to be disappointed – which may very well be the point – when fate wins out, or the characters beat their fates. Lost does bounce between the two, but ultimately comes down on the side of fate, which is more disappointing, because ultimately, the characters, while they might have improved themselves, they ultimately don’t affect any change on the world that makes their struggles worthwhile.

However, it is the character’s journeys that make the show worthwhile, and in the end, it’s not the end that matters, but the way in which they got there. Every character present in the show has changed somewhat – they arrived at the island broken people, and ultimately, the island healed them, allowed them to find closure, all the while providing them, and the viewer with a series of complicated, interesting stories that range from alternative history, philosophy, science fiction and quite a lot more. Lost has been quite a ride from beginning to end, and the lackluster finale to the show serves as more of an epilogue, rather than anything that is directly related to the story, and is something that provides a bit of an ambiguous, thought provoking ending, which is probably the best thing the show could have hoped for in the first place.

As noted earlier, I’m part of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Masterworks Review blog, and they’ve come up with an interesting meme, how many of these have been read? What I've bolded are books read and italics means I own it, but I’ve been meaning to read it. This list also includes new Masterwork releases coming out later this year and the first section of roman numerals of the list are a special run of hardcovers in the series, which are also in the numbered series.

I - Dune - Frank Herbert II - The Left Hand of Darkness - Ursula K. Le Guin III - The Man in the High Castle - Philip K. Dick IV - The Stars My Destination - Alfred Bester V - A Canticle for Leibowitz - Walter M. Miller, Jr. VI - Childhood's End - Arthur C. Clarke VII - The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress - Robert A. Heinlein VIII - Ringworld - Larry Niven IX - The Forever War - Joe Haldeman X - The Day of the Triffids - John Wyndham

1 - The Forever War - Joe Haldeman 2 - I Am Legend - Richard Matheson 3 - Cities in Flight - James Blish 4 - Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? - Philip K. Dick 5 - The Stars My Destination - Alfred Bester 6 - Babel-17 - Samuel R. Delany 7 - Lord of Light - Roger Zelazny 8 - The Fifth Head of Cerberus - Gene Wolfe 9 - Gateway - Frederik Pohl 10 - The Rediscovery of Man - Cordwainer Smith

11 - Last and First Men - Olaf Stapledon (Will be reviewing) 12 - Earth Abides - George R. Stewart 13 - Martian Time-Slip - Philip K. Dick 14 - The Demolished Man - Alfred Bester 15 - Stand on Zanzibar - John Brunner 16 - The Dispossessed - Ursula K. Le Guin 17 - The Drowned World - J. G. Ballard 18 - The Sirens of Titan - Kurt Vonnegut 19 - Emphyrio - Jack Vance 20 - A Scanner Darkly - Philip K. Dick 21 - Star Maker - Olaf Stapledon 22 - Behold the Man - Michael Moorcock 23 - The Book of Skulls - Robert Silverberg 24 - The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds - H. G. Wells 25 - Flowers for Algernon - Daniel Keyes (Will Be reviewing) 26 - Ubik - Philip K. Dick 27 - Timescape - Gregory Benford 28 - More Than Human - Theodore Sturgeon 29 - Man Plus - Frederik Pohl 30 - A Case of Conscience - James Blish

31 - The Centauri Device - M. John Harrison 32 - Dr. Bloodmoney - Philip K. Dick 33 - Non-Stop - Brian Aldiss 34 - The Fountains of Paradise - Arthur C. Clarke 35 - Pavane - Keith Roberts 36 - Now Wait for Last Year - Philip K. Dick 37 - Nova - Samuel R. Delany 38 - The First Men in the Moon - H. G. Wells 39 - The City and the Stars - Arthur C. Clarke 40 - Blood Music - Greg Bear

41 - Jem - Frederik Pohl 42 - Bring the Jubilee - Ward Moore 43 - VALIS - Philip K. Dick 44 - The Lathe of Heaven - Ursula K. Le Guin 45 - The Complete Roderick - John Sladek 46 - Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said - Philip K. Dick 47 - The Invisible Man - H. G. Wells 48 - Grass - Sheri S. Tepper 49 - A Fall of Moondust - Arthur C. Clarke 50 - Eon - Greg Bear

51 - The Shrinking Man - Richard Matheson 52 - The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch - Philip K. Dick 53 - The Dancers at the End of Time - Michael Moorcock 54 - The Space Merchants - Frederik Pohl and Cyril M. Kornbluth 55 - Time Out of Joint - Philip K. Dick 56 - Downward to the Earth - Robert Silverberg 57 - The Simulacra - Philip K. Dick 58 - The Penultimate Truth - Philip K. Dick 59 - Dying Inside - Robert Silverberg 60 - Ringworld - Larry Niven 61 - The Child Garden - Geoff Ryman 62 - Mission of Gravity - Hal Clement 63 - A Maze of Death - Philip K. Dick 64 - Tau Zero - Poul Anderson 65 - Rendezvous with Rama - Arthur C. Clarke 66 - Life During Wartime - Lucius Shepard 67 - Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang - Kate Wilhelm 68 - Roadside Picnic - Arkady and Boris Strugatsky 69 - Dark Benediction - Walter M. Miller, Jr. 70 - Mockingbird - Walter Tevis

71 - Dune - Frank Herbert 72 - The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress - Robert A. Heinlein 73 - The Man in the High Castle - Philip K. Dick 74 - Inverted World - Christopher Priest 75 - Kurt Vonnegut - Cat's Cradle 76 - H.G. Wells - The Island of Dr. Moreau 77 - Arthur C. Clarke - Childhood's End 78 - H.G. Wells - The Time Machine 79 - Samuel R. Delany - Dhalgren (July 2010) 80 - Brian Aldiss - Helliconia (August 2010)

81 - H.G. Wells - Food of the Gods (Sept. 2010) 82 - Jack Finney - The Body Snatchers (Oct. 2010) 83 - Joanna Russ - The Female Man (Nov. 2010) 84 - M.J. Engh - Arslan (Dec. 2010

So what's my count? 15 read, with a couple that I own. Hopefully, I’ll be getting to the two books of my own, Flowers for Algernon and Last and First Men, soon, after I finish up a couple of other things, but when they’re done, they’ll be up on the SF and Fantasy Materworks Reading Blog.

Bit of an edit here, 6 or more months on. I never actually ended up getting around to finishing or reviewing either book that had been my assignment - something I've been unhappy about, but more pressing matters have come up. Hopefully though, I'll be able to get to some of them at some point in the future!

I think most people will agree with me that this is a celebration that is well overdue and long anticipated by our respective families.Dan, Kate, you pocess something that has long been sought, but rarely known or experienced amonst those who strive for true love.In the eight years that I have wittnessed the two of you together, I've watched your love grow and mature with age. Love is not a singular collision of emotion and chemistry; it is a journey, one that must be taken with care and exploration together.Your marriage tonight is not the top of the mountain, but yet another starting point, a great milestone in your lives.Dan, Kate, you are facing a future of uncertain surroundings. With the love that you have for one another, you are the steady footing on which you march forward. It will help you through the best of times, and those that are most trying; it is the bright point that has brought you, and your families here together tonight, and may it shine brightly far, far into the future.

Fireworks and cookouts, along with the Red White and Blue that symbolizes our country, characterize July 4th of every year. At the same point, it serves as a good time for reflection on the creation of the country in which we live. The founding of the country is one that is becoming shrouded in myth, with its own set of misconceptions and happenings that are relatively unknown, which makes the constant 'Happy Birthday America' status and twitter updates that I've seen all along be somewhat of humorous statement.

When looking at the founding of the country, the 4th is an obvious holiday to look at, for it was the signing of the Declaration of Independence that formally succeeded the United States from the United Kingdom, and represented the first time that the colonies became a country that stood on their own. However, the founding of the country is something that has happened numerous times throughout our history, and at points, I wonder if the 4th is really a celebration of the beginnings of America, or something else entirely.

If looking at the founding of the country, it is also best to remember that the Europeans who came to the country weren't the first here. The numerous tribes of native Americans have been on this landmass for thousands of years, presumably since the end of the last ice age, when the glacier sheets receded and isolated the continent. They came down through North America and into Central and South Americas, creating their own vast civilizations. The Vikings landed in Newfoundland, Canada around 985-1008 by Lief Eriksson, but later abandoned the settlement. It was not until 1492, on October the 12th that Christopher Columbus, with the three ships under his command, the Santa Maria, the Nina and the Piñta, discovered the Bahamas, believing that he reached the Indies, before continuing down towards Cuba and Haiti. Return trips were planned in the years following his expedition, and soon, Europe was traveling to the newly discovered landmass in larger expeditions. In 1499, the new world was named 'America', after Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, who discovered that the new world was not Asia, but a large landmass in between the two. The first European to reach North America was commissioned by Henry VII of England, John Cabot, while others discovered more and more of this new world.

Looking forward three hundred years, the secession of the United States was preceded by decades of events and mismanagement by their British overlords, who taxed the colonies to help offset the massive expenditures of war and government abroad. Various taxes, such as the Stamp Act, Molasses Act Quartering Act and the Tea Tax fanned the flames of irritation against the British government, inciting riots and protests. The famous Boston Tea Party occurred in 1773, as the British government aided the failing East India Tea Company, bringing about the Tea Act, prompting a riot and protest on the part of the Boston merchants. War began a couple of years later in 1775, but clearly, the seeds of discontent had been laid far earlier, bringing about the declaration of independence from the colonies. On August 22nd 1775, the colonies were declared to be in rebellion, and by October of 1781, the British surrendered, and opted to not continue the war by March of the following year, and in November, the United Kingdom recognized the independence of the United States.

In March of 1781, the Continental Congress, began to work on a permanent form of government to lead the country, with plans stretching as far back as 1776, and by the time the war ended in 1781, the Articles of Confederation became effective, setting up a government that granted responsibilities, but almost no authority to maintain those responsibilities. There was a current of distrust in a stronger central government that ultimately crippled the Congress, for it could not regulate commerce, negotiate treaties, declare war or raise an army, create a currency, maintain a judicial branch, and no head of government that was separate from the Congress. While there were upsides to the government, it was unable to effectively govern, and a series of crises arose that threatened the stability of the nation. Shay's Rebellion provides a good example of this, when western Massachusetts went into open revolt in 1786 when the legislature failed to provide debt relief. This was but a singular example of the times, and there were more advocates of a stronger centralized government, where a revision to the Articles of Confederation were demanded, for a government that could regulate interstate and international commerce, raise revenue for the country and raise a single army to confront threats. The Constitutional Convention that arose sparked numerous debates over the rights of the state vs. the federal government (antifederalists vs. federalists, respectively). Despite the intense debate, the Continental Congress closed down on October 10th, 1788, and on March 4th, 1789, the new congress elected George Washington (who believed that the Constitution would only last about 20 years), and a new federal government was born. In a every way, this was the date in which the United States that we know today was formed.

This story of the birth of the United States and 'America', the concept, are important ones to remember, for not only the sequence of events that built upon the last, but their significance in relation to one another. Current ideology amongst popular culture nowadays seems to contort many of the lessons that can be learned from this period of formation within the U.S.. The United Kingdom was thrown off because of an apathetic and overbearing monarchy that failed to represent the interests of the colonies, rather than simply because of the taxes that were levied upon them. To hear senators and public representatives speak that the colonists rebelled simply because of a tax upon tea belies the complicated nature of American independence, and the lessons that were learned in the years afterwards of the failure of a weak centralized government, but also the simple fact that the Constitution of the nation was not the direct product of the American Revolution, but that it was a work in progress, of sorts. America itself, however, has had a series of births and rebirths, and the Declaration of Independence was but one such moment in the history of the nation, concept and location. Still, July 4th is a good of a time as any to celebrate the process, and the existence of the nation itself.

While I was overseas in England, I came across Gollancz's Science Fiction and Fantasy Masterworks series, a dedicated series of distinguished books in the genre, each with some very cool covers and a good list to start with for anyone looking to get into the genre, or at least, read through some of the fundamental reads. While it is not perfect - like any list, it's missing a number of books, and is heavily male-dominated (there are very few female authors represented, something that will hopefully change with future additions), and there's always personal preferences and new authors that will likely be added up at some point in the future.

I've joined with ten other book bloggers from around the internet blogosphere, under the direction of Patrick, who runs the book blog Stomping On Yeti, who conceived of the project after realizing that he owned all of the books, but had yet to read the hundred and twenty-three in the series, save for a handful. After a call went out to the various corners of the internet, a small group has been assembled to read through the entire list, contributing reviews on the books in the series, hopefully providing a good resource for speculative fiction fans.

I'm looking forward to helping out with this project, having read several books represented in the series, but with a couple of books that I have yet to read set to go, Flowers for Algernon, by Daniel Keyes and The Last and First Men, by Olaf Stapledon. Thus, the project provides a good opportunity to read several books that I haven't had a chance to get to, but also a good opportunity to reread some books in the near future that I haven't read for a couple of years.

Furthermore, the project is a cool crowd sourcing style project that brings together the writing abilities and expertise of a number of writers who largely look at new and upcoming books within the speculative fiction genre. There have been some larger literary projects, such as 1 Book, 1 Twitter, which has recently been moving through Neil Gaiman's American Gods, which brings together thousands of people reading the same book at the same time, and this one brings together a much more qualified group to look over an entire series of books as a whole.

Ultimately, I hope that there will be some good discussion not only about the books and their merits (or lack thereof), but also of the series, the selections, and multiple viewpoints on similar books to get a very comprehensive look at the books and series, but also at the underlying idea of what is Science Fiction and Fantasy, as larger genres. Finally, the last question that can hopefully be addressed is what books should be included in any sort of masterworks list? Given that a number of the contributers look to new and upcoming books, it will be interesting to see what has come out recently that will be considered a classic.One of my books is currently being read, and I'll hopefully have my reviews up and running soon enough.

The site can be found here: http://sffmasterworks.blogspot.com/

This summer’s entry in the Todd Lecture series at Norwich University was Pulitzer Prize winning author Rick Atkinson, former reporter for the Washington Post and author of several of books, most notably, An Army at Dawn, about the Invasion of Africa (which won him the Pulitzer in history), and more recently, The Day of Battle, about the invasion of Italy, both part of his epic trilogy on the events of the Invasion of Europe. In an already cluttered field of works on the Second World War in Europe, Atkinson’s books stand out immensely as some of the best books about the conflict, and the third book, of which he’s completed the research for, and is now outlining and writing, will be out in a couple of years, and will undoubtedly be a gripping read.

Atkinson spoke about an important and relevant topic to the history graduates before him: the value of narrative history, and more specifically, the need for a writer to recognize the value of a story within the heady analysis and synthesis of an argument. Personally, I find the division and outright snobbery of most academic circles to be frustrating, especially when it comes to popular and commercial non-history. Within history is a plethora of stories, values, themes and lessons to be breathed, learned and valued, and an essential part of education is bringing across the message to the reader or general audience in a way that they can comprehend and relate to the contents of any historical text.

Commercial nonfiction has its good and bad elements to it. Bringing anything to a general audience can water down an argument, and the balance between good stories and good history is one that has to be balanced finely. Some authors do this well, and from what I’ve read of Atkinson’s books, he has done just that.

Mainstream history is important. It is what helps to bring the lessons and analysis of the past to the people, and a population that reads and learns from their historians is a population that can intelligently call upon the past to make decisions for the future by comparing their current surroundings to similar happenings in the past. More than ever, this is important, and Atkinson’s talk and follow-up questions help to drive this point home.

Atkinson’s books are in the unique category of bridging the divide between academic and popular reading, and he noted that the failed to believe that history needed to be dry, uninteresting and irrelevant. History does not need to be relegated to only the academic circles, but it should be something that is in the foremost thoughts of the American population.

History is important, not just because of the lessons that are learned from it, but because of the mindset that is required to comprehend it. History is not a record of events gone past, but of the interpretation and story that those events tell. What is required from those who examine the field is an understanding of how a large number of events, political and societal movements and individuals all come together in a sort of perfect storm to create the past. Much of this is cause and effect, and contrary to popular belief, the past holds no answers for the future: it is the understanding of how said events occur, within their individual contexts that allow for the proper mindset to understand how similar happenings might happen in the future and how to prepare for what is to come.

Atkinson’s talk was a good one for students to hear, and different approaches to history are simply the nature of the field. The Military History students who graduated last week were ones that have a large number of options open to them, and Atkinson’s talk (and his own stature as a historian) demonstrated that a doctorate isn’t the only way to make a living at this.

You can watch Mr. Atkinson's talk here.

In a world with sparkling vampires and an abrupt popularization of the genre, the 2010 film Daybreakers comes as a welcome addition to the genre, blending science fiction, dystopian thriller and vampire lore into a neat, exciting film that had a sensible story with a great visual sense. The most interesting thing is that it's really not about vampires at all: it's about oil.

In 2009, an epidemic raged across the world, killing almost everyone and turning them into vampires. There are no new innovations here: the vampires avoid sunlight, wooden stakes cause them to explode in a bloody mess, and, of course, they drink blood. By 2019, society moves along like it always did, just during the nighttime hours. Ethan Hawke portrays Edward Dalton (hopefully better than the other vampire Edward...), a sort of vegetarian vampire who lives off of pig blood, who works for Bromley Marks, a pharmaceutical company looking to make a replacement for the rapidly dwindling supply of human blood. Dalton comes across a member of a human resistance movement, who knows about his work, and brings him together with someone who had cured himself of the aliment.

Daybreakers is remarkably well thought out, from the story to the background elements. Happily, the film takes much of the traditional vampire lore and shifts it into the future, holding onto only what is strictly necessary, and adapting everything else to what the story requires. Cars are fitted with shades and external cameras, sidewalks are moved underground, soldiers wear protective clothing, and houses have alerts for their owners to know when there's a risk of sunlight. Everybody is immortal, and it seems like it could be a very good life.

What really works well in this film is the attention to detail, on a story, visual and background level: the film doesn't feel like, nor is it, fluff. There's a good amount of attention to the story, which moves along briskly, with quite a bit of action, encompassing a number of elements, all along with a really striking visual sense that helps the film really stand out from most of its compatriots. Particularly striking was the lighting, with dim grays and blues for a lot of the vampire scenes, but also bright and solid yellows for the humans, creating a sort of unconscious divide between the characters and their respective storylines when they showed up. This has been done to great effect in other films, such as Pan's Labyrinth and the television show Firefly.

The main problem that faces vampire society is that there is a critical shortage of human blood. Humans, only numbering around 5% of their original population, or around 342 million, have been captured in massive blood banks for the likely population of 6 billion vampires. As the human population declines, the vampires transform into is a horribly mutated one that looks a bit like an oversized, insane bat (a subsider), which an entire populate is at risk of transforming into, and understandably, there is quite a lot of panic in the streets, and the very problem that Dalton and the Bromley Marks company is trying to avoid. Dalton comes across problems as he comes up against corporate interests, who are only interested in the status quo, with the ability to sell pure human blood to the highest bidders, while keeping their form, as opposed to the complete reversal of the condition that everybody is afflicted with.

This conflict is at the center of the film, and at the heart of it, it's really not about Vampires, but it's about the modern world's complete dependence upon oil. Oil, which helps hold the world together as we have become increasingly globalized, is a resource that will eventually run out, and will leave much of the world in a state of decline, due to short sighted business interests who only are interested in pleasing shareholders. The same holds true in the film, and given that there was a decade of vampirism on earth, it seems somewhat astonishing that they would have completely squandered their lifeblood (literally) until you realize that that's exactly what is being done at the moment, with any number of things. The film gets a good message throughout the film, fulfilling some important aspects of what the genre should be doing for its audience.

Ultimately, the environmental storyline is the strongest component in the film. There are good attempts at a personal story and some work towards the characters, but ultimately, after watching the film, it feels like there was a lot missing: tantalizing hints, such as Dalton's transformation and his subsequent relationship with his brother are largely left up in the air, as well as a couple of similar storylines that involve some of the other characters in the film (Sam Neill's character, Charles Bromley, and his daughter, for example), all add to a fascinating background and world that has been constructed for this story, and at points, it feels like there is elements or scenes that are missing that would really flesh out the film, such as the introduction of a vampire senator who harbors human sympathies. The film would have been further strengthened to better sort these out, and it's certainly possible that a director's or special cut would rectify this sort of thing.

Ultimately, Daybreakers isn't totally sure of what it should be: character or political drama with the coverings of a genre film, or something else. As it stands now, the film is a very good one, covering much ground and providing a nice addition to a fairly crowded speculative fiction genre. The film holds a good message, and has all of the right elements going for it, making it a really good, worthwhile film to buy, but it falls just short of being a really fantastic, must see watch.

One of the best moments in Hellboy II: The Golden Army occurs when Hellboy and Abe Sapien walk up to a little old lady, burnishing a canary towards her, prompting her to open up a door to allow them into the Troll Market. The scene itself it laced with humor, a sense of weird paranormal happenings and quite a bit of fun. The scene ends when Hellboy punches the lady (who's really a troll), and the audience knows right then and there that the movie isn't a serious affair, but something that the director and cast clearly had quite a bit of fun with.

The film, which follows up 2004's Hellboy, is an adaptation of Mike Mignola's comic book by the same name. Like the first film, it plays off of some of the stories, but is creatively seperate from the books. In this regard, director Guillermo del Toro is possibly one of the best directors to take on the franchise, and brings his own vision to the screen.

I've been a fan of the comics, particularly because of Mignola's unique artwork and the rich gothic and paranormal elements to the issues that I've read. It's a very fun comic, and one that has a lot of depth and meaning to it. The first film was a decent adaptation of the films, but by far, Hellboy 2 feels more at home in the world that Hellboy and the BPRD team inhabits.

For all intents and purposes, Hellboy: The Golden Army could be Hellboy: BPRD, for most of the team from that particular line of comics is present: Liz Sherman, Abe Sapien and Johann Kraus, who investigate an event at an auction house, which brings them into a plot orchestrated by Prince Nuada, who seeks war against humanity. He intends to reactivate the 'Golden Army', a race of mechanical warriors that had been stood down before. Hellboy and BPRD travel around, from the Brooklyn Bridge to Ireland.

There's some truly great moments here in this story. The Troll Market hidden under the Brooklyn Bridge far surpasses any of the magical and fantastic that's been seen in Harry Potter or similar films, and recalls del Toro's prior film, Pan's Labyrinth, with it's subtle elements. Ever since watching that film, I've been enamored of his vision of the world, and he's really the perfect person to take Mignola's own work to the screen.

Visually, the film is quite a bit of fun, although at points, I felt that the story was a bit lacking. The narrative gets off the rails for some of the character moments, and at points, the film doesn't know what it really wants to be about: Hellboy's own relationship with Liz Sherman, his out of place nature with the world and his own destiny and the story at hand. Between the three, the story feels somewhat stretched, especially as some of the same ground has been covered already in the first Hellboy film.

The only other thing that really bothered me was Johann Klaus. He's a very interesting character from the BPRD side of the house, but in those comics, he's really a consultant, not the leader that we see in the film. His character, coupled with a suit that was just a little too dynamic (hissing vents, really?), fell largely flat, given my expectations from the comics. Still, this is an adaptation, and as such, I'm not expecting the entire thing to be exactly like the comics.

Still, the film is quite a bit of fun, and a worthy addition that leaves the story somewhat following what's happened in the comic books (to my knowledge - I'm not overly familiar with the entire storyline - something that I'm looking to correct.) It'll be interesting to see if a third film is followed up, because the first two really set up some elements towards that end. However, my preference remains with the comics and their unique art and stories.

In 1983, the term Cyberpunk was born, with a story by the same name by author Bruce Bethke in Amazing Stories #94. The term is defined as a "[S]ubgenre of science fiction that focuses on the effects on society and individuals of advanced computer technology, artificial intelligence and bionic implants in an increasingly global culture, especially as seen in the struggles of streetwise, disaffected characters. (Prucher, Jeff, Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction, 30). The word itself comes from the meshing of 'cyber' and 'punk', which to me has always seemed as an electronics rebellion. Certainly, the subgenre is one that presents drastically different stories and meanings than what had traditionally been science fiction, and in a way, the style represents a degree of cutting edge thinking that really belongs to the first on the scene, with the truly unique and original thoughts that go against the grain. I think of cyberpunk as the books that are out looking for a fight, ready to cut those unprepared with what they have to say.

My main issue here is two-fold. The first is that with that in mind, it's hard to apply that sort of label to any sort of science fiction after the term is pushing 30 years old, much as it's hard to take someone seriously who's been involved in the punk scene for a comparable amount of time, with several records under their belt to a major record label. The surprise and edge vanishes after a while, and in a way, the 'Cyberpunk' term has become a label that's synonymous with electronics and dystopia. At the same time, the suffix '-Punk' seems to be added onto any number of themes and styles of science fiction literature. Steampunk is a ready example, both visually with film, photography and costuming, but also with such books as Cherie Priest's Boneshaker, where there is a blend of dystopic and steam-powered technology. The problem that I see is that the idea behind 'punk'-style music, video, literature is that it's something that ultimately rebells against a label, and in science fiction's field of vision, -punk is the marketing term to rally behind in creating a subgenre, undermining or missing what the word in the meantime really means.

The term itself came at a time of globalization and a rise of technology around the world, and has since become a label for any number of stories that correspond to a use of technology, with dystopic and near-future themes. Promoted by Gardiner Dozois, the term has largely been used to describe books by William Gibson, Philip K. Dick, Bruce Sterling, Neil Stephenson, and many more. Neuromancer really cut in close at a time before the Internet and home computing, creating a vision of the future that was wholly unique, interesting and edgy. In a large way, the term really did apply to a lot of these earlier books. (This is not to say that modern books in the 'cyberpunk' genre are bad - far from it. This isn't a specific criticism at the books within, just at the association and labeling that they're saddled with). Like observing a quantum event, you change the picture simply by looking at it, and in effect, calling something 'punk' undermines the meaning of the term, and ultimately, does the books labeled as such a big of a disservice. In this day and age with computers and virtual worlds becoming the norm, computers and electronics aren't necessarily that edgy, and any book written in the genre will most likely be compared to Neuromancer in some way or form.

At the same time, I've long been irritated by the Steampunk genre as a concept. According to Brave New Words, the term was coined just four years later by K.W. Jeter in a letter, noting that he believed that stories set in the Victorian era will become the next big thing, and suggested the term Steampunk, most likely in relation to the same edgy connotations that '-punk' gave the word 'cyber'. Once again, the idea of the word 'punk' being used as a label, especially a label right out of the gate, goes against all of the rebellion and fire that the term really should hold for that which it describes. Steampunk is a subgenre that is really beginning to grow a bit more, but doesn't feel new or edgy as far as its content goes: much of what you can see in the stories has long roots in the genre: the stories of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, for example, could easily fall well within the common definitions of Steampunk, and they did it when the concepts were really new and punkish in their own right. (Wells, especially, went across the grain in his literature and his personal life). Thus, a lot of this current steampunk fad is a retread over old ground, with stories that tell drastically different things this time around. Cherie Prist's latest book, for example, isn't so much about technology as it is about character inter-relations in a steampunk-styled environment, one that I'd really label as alternate history over Steampunk. The same goes for recent books by K.J Parker with Devices and Desires, Christopher Priest's The Prestige and Ekaterina Sedia's The Alchemy of Stone. I've long believed that the term science fiction, fantasy and speculative fiction in general really transcends the content and goes far more towards the themes, plotline and characters of each work.

Still, there seems to be a tendency for new genres to be bestowed with the '-punk' suffix to differentiate various groups of works by content and theme to perfectly define its own little sub-genre and capture a specific audience. In a large way, it's a good move on the parts of publishing marketing departments to better make their books sell: define an audience, and target them. In some cases, it's warranted. The stories of Paolo Bacigalupi, for example, such as The Windup Girl, The People of Sand and Slag and The Calorie Man, all exist within stories that are defined by their environmentalism-styled stories, ones that have a clear and defining message within a near future, influenced by current events. I've seen others, and called them myself, bio-punk, because in a way, they are some of the more raw, unique and though-provoking stories that I've yet seen. I'm sure that there are other stories, (including the upcoming story at Lightspeed Magazine called Amyrillis, by Carrie Vaughn), that looks at the environmental future and the speculative elements of the next several decades, at the same level of intensity as the early Cyberpunk stories. At other points, I've seen a tendency to apply the label to other things that really don't warrant it, and I can't help but wonder if '-punk' has just become synonymous with 'subgenre' or 'cool'. With the rise of steampunk and cyberpunk, what's to say that there won't be a major movement like 'biopunk', but alongside such things as woodpunk, ironpunk and stonepunk, each with their own style of stories, each more ridiculous than the last? In this possible future, Homer's Iliad, Odyssey and the entirety of the Greek myths will be re-categorized as 'Bronzepunk', and the Apollo-era of space stories will be titled 'Vacuumpunk' (which will most likely be re-titled for ironic effect, vacuum pump fiction).

The main question behind all this is that if the term '-punk' becomes an expected title for any style of sub genre, does it really convey the same meaning as it did in those early days, when? I think that it doesn't, because the idea behind the term is that the fiction is unexpected and raw, and placing the label on it becomes an effective, safe bandage that soothes what shouldn't be. The fiction isn't at fault, it's the hype behind it. Ultimately, speculative fiction as a whole is done a disservice by the constant subgenres, which separates out everything into miniscule categories that are ultimately meaningless, governed and sold based upon their superficial elements, but not the central themes that ultimately make a story worth reading. Punking a genre seems to be the epitome of posing, especially if the term is simply applied to a brand of stories for the simple purpose of finding a market for them.

One of the films that I've watched lately that's become a real favorite of mine is 1982's TRON, which told what I feel is one of the better stories about artificial intelligence and the future of computers. The movie is a dated one, given how much computers have changed in the past thirty years, but I feel that it holds up extremely well, even in the modern computing age. Given the craze in Hollywood over the past decade for sequels, it comes as no surprise that a sequel for TRON will be released later this year. What is surprising is just how long it's taken (28 years!) to make a sequel. Except for one thing: the film has already been remade with another hit: The Matrix.

I saw The Matrix first, about a year or two after it was first released, and really enjoyed it. The combination of martial arts, cyberpunk and gothic themes blended together into a genuinely smart science fiction thriller worked extremely well, even extending into the sequels, which I thought were decent (although they certainly suffer from the 'More is Better' mentality that sequels are often saddled with), especially with some of the themes that were introduced in Reloaded and Revolutions.

When I watched TRON this past fall, I was astonished at some of the marked similarities between the two films. The Matrix is a film that plays homage to a number of films that influenced the Wachowski Brothers early on, and it's easy to assume that much of what is consistent in The Matrix is influenced from TRON. Some of these similarities are in the form of the visual nature of the film - the opening title sequences are nearly identical, as are some camera angles and scenes. Moreover, the story idea of a person entering a completely digital world is a major similarity between the two, and is certainly not something that's tied only to TRON. (William Gibson's fantastic thriller Neuromancer comes to mind) But in the visual arts, it's clear that there's quite a bit of TRON in The Matrix.

What made Steven Lisberger's film so interesting to me was the real depth to the story, and the religious connections that were placed there between the programs in the computer systems, and the mythical users who created them. Like any good story set in a speculative fiction universe, the story extrapolates from the fantastic and has several themes that are relatable to the audience watching the film. Here, there is a link between the cold and analytical electronics, with an element of the supernatural to the beliefs of the programs. Moreover, it changes the viewpoint of a program to something that's highly relatable, as people with fairly specific purposes within the innards of a computer, while the user, a creator of programs, is akin to a god in the machine.

The Matrix incorporates some of these elements in TRON, where Neo proves to be an exceptional person within the programming of the Matrix, someone who can ultimately conceptualize and realize the full extent of his abilities within the Matrix - he's able to alter the reality around him in order to accomplish extraordinary things. Neo is essentially superman within the computer, with a number of religious connotations surrounding him throughout the story.

With the coming Tron: Legacy film coming in December, the question has to be asked: is it necessary? In the follow-up Matrix films, we see that there's an environment that is very similar to the world that TRON presents, with programs acting on their own in their own little world. This seems to be where the next TRON is exploring, with a new world with better graphics (literally in both cases), but in a way, the Matrix films acted as a reboot to the 1982 film in their own way. The hope with film producers is that this new TRON film will become the start to a new franchise of films, with a trilogy and television series planned (at least that's the rumor). There's a number of ways that this story can go, and it will be very interesting to see just which direction can be taken with the future films and productions.

When it comes down to it, however, The Matrix is really a highly stylized, slightly different version of TRON. The protagonists in each film are largely the same: challenge a malevolent computer program and overlord within ambitions to control humanity. There are some differences here between the two, but for all intents and purposes, the Matrix has a similar enough story and had the same impact as its predecessor.

Hopefully, the upcoming TRON film will fare better than its counterparts in the Matrix trilogy, providing an interesting and thought provoking sequel to a film that really sparked that in the first place. Both the Matrix and TRON were excellent films that arguably changed the genre of science fiction film.

Author Michael Williamson recently came across my article on io9, and posted up his own response. He makes some good points, but I wanted to address some of the areas where I disagree.

I have a couple of counterpoints to this that I'd like to address. I haven't had a change to read through all of the comments and address them individually, but I'll try and point out a couple of things that I think need corrected from the article above and my own on io9.

The first, major point is that no, I don't want Clausewitz to write science fiction. After reading his works for my Military Thought and Theory course (I've received an M.A. in Military History from Norwich University. For my own disclosure, I work for the school and that specific program as an administrator for the students, but the Masters degree really pushed me in terms of what I knew and how I understood the military), I think he's one of the more dry reads that I've yet to come across, and that while there is a lot of outdated information in the book, given the advances and changes in how militaries operate, there are some elements that I feel work well, conceptually.

The main point in the article wasn't written to say that military science fiction had to be more like a Warfare 101 course in how future wars should be fought - far from it - but that military science fiction could certainly benefit from a larger understanding of warfare. As you note, there's a lot of military themed SF stories about the people caught up in warfare, ones that examine how they perceive warfare, and how warfare impacts the individual in any number of ways. This comes in a couple of ways, one story related, the other more superficial.

There are very few (I can't recall any that specifically look to this) military SF novels that look at warfare in the same context. While I agree that stories are about characters, it's also the challenges and the subsequent themes that embody their struggle that makes a story relevant and interesting to the reader. This, to me, as a reviewer and reader, is the element that will set up a book for success or for failure. Characters, the story/themes/plot, and the challenges that face him all work together to form the narrative. What the characters often learn from their challenges is what the reader should also be learning, and this, to me, is a missed opportunity for some elements of military science fiction. A majority of the Military SF/F stories out there have the characters impacted, but warfare is generally painted as a element of the narrative, not something in and of itself that can be learned from.

Superficially, wars are incredibly complicated events, and often, I don't feel that they're really given their due in fiction. There are a couple of points that I want to make in advance of this – this doesn’t mean that I want or require more detail on every element of warfare, from how the logistical setup for an interstellar war might be put into place, or how the X-35 Pulse rifle is put together to best minimize weight requirements in order to be effectively shipped through lightspeed. Those sorts of details aren’t important to the character’s journey in this, and they add up to extra fluff, in my opinion. Weapons and systems put into place for warfare are great, they sound great, and the same arguments are put into place in politics today. What makes the better story, in my opinion, is a better understanding of the mind behind the sights, from that individual soldier’s motivations to his commanding officer’s orders and training, and how war is understood on their terms. In a way, world-building for any story should firmly understand just what warfare is, or at least come to a consensus within the author’s mind as to how it will be approached.

Oftentimes, generals are accused of fighting the wars gone by. That’s certainly true in the ongoing conflict in Iraq/Afghanistan, and why there was quite a bit of resistance in shifting the military’s focus over to a counter-insurgency war, rather than one of armored columns and maneuvers: generals fight with what they have, and what they’ve trained for, and changes come afterwards. Starship Troopers, The Forever War and Old Man’s War all do the same thing, and that’s not really what I’m arguing against – the authors wrote what they knew – Heinlein, undoubtedly from his experience with the Second World War, Halderman from his own experiences in Vietnam, and Scalzi from observation and research. Science fiction looks to the future, but unless you’re a dedicated expert in a think tank, there’s really no expectation that these books will be predictors of the future, but also aren’t necessarily going to be good at the military thought and theory behind the battles on the pages. Will the individual soldier know anything about logistics and engineering solutions? Probably not, but those things certainly will influence how that soldier is operational on the battlefield, which will undoubtedly affect his view and outcome on the battlefield. While these elements might not surface in the text, they should be understood.

Art is formed within the context of its formation. I don’t believe that a book written in the Post-WWII world should be really in depth on theoretical warfare on the character level, nor should it look beyond what the audience and writer really understands. However, as times change, context changes, and books are understood differently. There is no doubt in my mind that we will see science and speculative fiction stories in the next decade that are directly impacted by our understanding of the world since 9-11 and the warfare that has come as a result, because the current and budding writers are also changing their views on the world.

I see most military science fiction like I see some types of military non-fiction. Stories like Starship Troopers are like Band of Brothers. They’re fun and good character stories, but anything by Stephen Ambrose is certainly not serious military nonfiction, and isn’t something that I would use to better understand the nature of the Second World War. Looking at a similar book, The First Men In, by Ed Ruggereo, is a better example, (one that I recommend highly, as a counterpoint), but that tells a good character story AND looks at the strategic nature of Airborne operations during Operation Overlord.

Military Science Fiction can best be summed up as soldier science fiction, with the characters learning much about themselves and society – that’s never been in dispute from me. What I would like to see someday added to a field is a novel that better understands the nature of warfare, and extrapolates some of the lessons that can be learned from it.

The shared groan that my girlfriend and I shared as the end title card for the last episode of Stargate Universe’s first season, Incursion (Part 2), has become a familiar reaction to the ending of each episode of the series that we've been watching, and reminds me of the reaction that I've generally had for the season enders for Stargate SG-1 and Stargate Atlantis, as well as Battlestar Galactica. The ending to SGU's first season was shocking, frustrating, and ultimately, a fantastic end to a really strong season for the Stargate franchise's latest television entry.

The SyFy channel has a really annoying habit of leaving a viewer hanging, and it was something that largely characterized SG-1, with a small story arc that would be resolved within the first couple of episodes of the next season, and while it's annoying, it's a good way to make people really look forward to the upcoming season - already, I'm eagerly awaiting September, when new episodes return to the small screen. The finale demonstrated that the franchise, with its much darker nature, can continue to tell a good story, but also link back to the regular Stargate franchise and storylines that had been started earlier on, something that was a welcome surprise.

The start of Stargate Universe led me to believe that much of the storylines would be somewhat ignored, pushed to the side for some background context for the characters, but that was it. As the story has progressed since that first, fantastic pilot episode last October. The show has taken a couple of hits with its characters and some of the smaller elements, but overall, it has come out the other side in good form, telling some truly fantastic stories, and leaving the audience really wanting a bit more as the story of the crew of Destiny shows that there are some pretty cool things planned.

The surprising element that I've found over the course of the show was the connections to Earth, and the recent reintroduction of older storylines that had begun to creep in at the end of SG-1's run, namely, with the Lucian Alliance. While it's pretty clear that the show is going to remain on Destiny for now, and that much of what we've seen thus far will continue, the introduction of other storylines gives this show something a bit different than what we've seen in other shows, like Star Trek: Voyager and to a lesser extent, Stargate: Atlantis. The ongoing storylines that we've seen show that some of the groundwork that was set up in SG-1 will still apply, and unlike in Atlantis, where a whole new story arc had been put into place, with some of the prior story elements coming in only occasionally. Hopefully, this new approach will work better, resulting in a series that lasts for longer than Atlantis fared. SG-1 demonstrated the lasting appeal of the show, and thus far, nothing has been able to replicate that.

Universe also shows that the franchise can move beyond SG-1 by incorporating more mature and darker elements to it. SG-1 was a fairly lighthearted affair most of the time, but Universe can be downright grim, but it maintains much of the fantastic storytelling and characters that the Stargate franchise is known for. This makes quite a bit of sense, given the prior successes of Battlestar Galactica, and that as the surrounding times change, the context for the show changes as well. The original Stargate came out in 1997, preceded by a movie, with the United States facing off against an evil empire that wanted to enslave humanity, just seven or so years after the fall of the Soviet Union, where the United States faced off against a singular power that threatened its influence in the world.

Universe seems to mirror that change in politics, with the crew of the Destiny moving into an ambiguous world where the enemy is not clearly known. While I doubt that it is an example of the show's creators explicitly going out and looking at political science and social theory to help construct the show, it is a good example of how the show, and the entertainment arts are generally influenced by the world around them. I think that this is the key element that allows for something to become relevant, notable and ultimately successful, because an audience will respond to something that they themselves can understand and perceive.

The good thing in all of this is that the show has come around full circle, leaving a lot of the familiar elements of the prior shows, where it finds itself in the middle of larger storylines that had been in progress. Universe, which had tried to largely escape from the rest of the franchise's image, has come back, serious, determined and ready to take them on. The Goa'uld ships look better than they ever have, and the villians are just as evil and ready to kill people, but without the costumes and things that made the show a little more difficult to take seriously. In short, Universe is the grown up Stargate SG-1.

As such, this was one of the strongest points of Battlestar Galactica, and with the follow up show, Caprica, and it remains a strong, if somewhat subdued element with the new show. As such, it is a good thing for the franchise, giving the show relevancy and some new ground to cover for the characters in the show. There’s absolutely no doubt in my mind: I’ll be tuning in for Season 2.

Ashes to Ashes, the follow up show to 2006’s Life On Mars, ended on a high note, finishing out the series and presumably the entire franchise, answering some questions lingering from Sam Tyler’s experiences in 1973. At the same time, Ashes to Ashes has continued an interesting story, pushing the stories to the extremes of the medium, and providing a genuinely surreal experience for the viewer.

In 2006, Sam Tyler, a Manchester DCI, was hit by a car and awoke in 1973. Discovering the reasons for his abrupt time travel, he returned to the present, only to commit suicide and return to the land of Gene Hunt and his band of lawmen. Ashes to Ashes picked up the pieces shortly after Tyler’s death, with police officer Alex Drake receiving a bullet in the head, propelling her back to 1981, where she navigates the past once again to try and figure out just what is going on.

The show had a lot to live up to: Life on Mars, likewise named for a David Bowie song, provided one of the more interesting, exciting and thought-provoking show to hit the airwaves. A gripping look at changing values in a country that has changed dramatically, the show did exactly what good science fiction should do: present a story in different contexts. In this instance, it does it quite literally, but the original show introduced an element of surrealism to the storyline, something that Ashes to Ashes has continued.

A sense of the surreal has been a larger part of Alex Drake’s storyline. A police psychologist, she was an investigating officer when it came to Sam Tyler’s case, and throughout the show, recognizes that her surroundings aren’t real, whereas in the prior show, there was an element of uncertainty to Sam’s predicament, right to the very end. Life On Mar’s finale revealed that Sam had been killed, and Ashes to Ashes does a fantastic job carrying the momentum forward, delving further into the franchise’s mythology, characters and story.

One of the best points about the show was the return of Gene Hunt (Philip Glenister), Ray Carling (Dean Andrews) and Chris Skelton (Marshall Lancaster), and newcomers Alex Drake (Keeley Hawes) and Shaz Granger (Montserrat Lombard) who brought back a fantastic performance and new direction for the storyline. Rather than repeating the successes of its predecessor, which mainly focused on procedural elements (as well as Sam trying to return home), much more of the back story to the cast is brought in, and it’s clear that Gene Hunt has remained at the forefront of the action, metaphorically and literally.

While I’m not convinced that Ashes to Ashes had a better ending than Life on Mars, it was a good one, wrapping up where Life On Mars left off, and making it clear that Life On Mars was just one story in a much larger one. Gene is revealed to be something of a main figure in a purgatory for deceased police officers, helping them settles the major problems that they all faced before releasing them from that existence. The world of Gene Hunt is one of the restless dead, and he is their shepherd, acting out all of his own flaws and insecurities in the meantime.

In the run up to the finale, the surrealistic elements really come to their proper form, as Chris, Ray and Shaz begin to realize that their lives aren’t what they seem, and the points where they watch their own deaths is an interesting one, revealing much that’s been build up around the characters over the past three seasons.

I’m rather sad to see the show go away, and with the reveal at the end, it’s pretty clear that this franchise is largely at an end, something that I both applaud and lament. On one hand, it feels as though this sort of storyline really could have used a third series to better build up the suspense and tell some interesting stories. I would have loved to have seen a series set in the 1990s (which is coming up on the 20 year mark soonish), but at the same point, the BBC has had the foresight to really end the show before running it into the ground, something that American channels do only inadvertently when they can’t figure out how to market a television show to an audience. Life On Mars is a particularly hard one to sell, and here in the U.S., it failed to garner a second season, although they did do a decent job adapting the story – until the end.

The main problem with the Ashes to Ashes ending was that we already really knew what had happened to Sam: he’d died, and returned to the sort of dream world, and the revelation that Gene Hunt was a specter of coppers deceased really isn’t the surprise that it should have been, all things considered.

With that in mind, the final episode was far more intriguing than anything that I’ve really come across in U.S. mass media, and very rarely can something as interesting and surreal (Twin Peaks, Pushing Daisies, and LOST) as Life On Mars and Ashes To Ashes come onto our television screens. It’s a real shame, but at the same time, it’s good to treasure those shows as they do come across.

Very rarely do I come across a book that literally keeps me up nights with a flashlight, reading into the late hours, just to finish one more chapter, just one more, before sleep overcomes me and I'm forced to place my bookmark in place to continue reading the next day. There are a lot of books that I'm interested in, fascinated by, but there are very few that capture me with a interesting story and a writing style that makes the pages blur as I read. Cherie Priest's 2009 novel, Boneshaker did just that over the past couple of days. Boneshaker is one hell of a story, one that left me wanting more whenever I set the book aside. Capturing a trio of geek obsessions, Priest's novel is a compelling work of alternate history that blends zombies with steampunk, villains and mad scientists, all swept together in a story that was quite a bit of fun to read. Nominated for the prestigious Nebula and Hugo awards (It lost out to Paolo Bacigalupi's The Windup Girl for the Nebula), and armed with a good number of critical praise, Priest has quite a bit to be proud of with this book. Set in an alternate past, where the American Civil War has dragged on for nearly fifteen years, the city of Seattle is dying. Sixteen years prior to the beginning of the story, a machine, designed to mine gold in the frozen Klondike, destroys part of the city, unleashing an unimaginable horror upon the city: the Blight, a corrosive gas that kills all who breathe it, and reanimating their bodies and awakening them to a hunger for human flesh. The survivors of the catastrophe walled off the infected area, and began to move on with their lives. Sixteen years later, Briar Wilkes and her son Zeke eke out a meager living, plagued by their associations with the man responsible for the disaster, Levi Blue, Wilke's former husband, and Zeke's father. Determined to clear his family name, and to get some answers for himself, Zeke descends into the broken and poisoned city to uncover clues of his family's heritage, while Briar follows. Both discover that behind the Wall, survivors of the disaster form their own living, escaping the Blight and its victims, and living under their own rules. Briar is the only one who can save her son amongst the pirates, criminals and survivors in the dead city. Boneshaker is a fun story that draws upon a number of strengths to really succeed. While the book is an incredibly easy sell to anyone marginally interested in science fiction, fantasy, horror and other speculative fictions, its strengths lie more in Priest's storytelling and world building than the zombies (or Rotters, in this instance), steampunk brass or the action. Rather, she places all of these elements within a compelling alternative United States, and populates it with characters that are both well conceived and caricatured, forced into action with a story that fits everything together nicely. I really like the alternative America that Priest sets up, especially as a historian with a background in military history. Here, the Civil War has stretched on for over fifteen wars, with the Union slowly winning. Key military leaders remained alive, and because of the continuing war, technology continued to advance. As a result, there's airships, machines and other pieces of technology that somewhat makes sense with the events of the story. In doing so, an entire world has been created, with quite a lot of background information that Priest can draw upon, not only for Boneshaker, but for other books that are forthcoming in this world, titled the Clockwork Century. Last year, I was certainly aware of Boneshaker, but personally, I'm not a huge fan of zombies or steampunk, and the entire notion really turned me off, simply because most of what I've seen of the Steampunk genre really doesn't make logical sense to me. Simply adding glass and copper attachments to something mundane for the sake of making something historical 'interesting' just bothered me, because of the historical precedent behind it. What Priest has done, however, is put the advances in technology into a historical context that makes quite a bit of sense: historically, warfare is a major incubator for new technology, generally beyond the weapons used on the battlefield, and with items that have a number of uses that can be applied to a post-war period. Duct tape, the microwave oven, jet planes and radar, all technologies that are in commonplace usage today, owe their existence to warfare as a catalyst for their development. Priest seems to understand this, and in interviews that I've read, it seems that she's done her homework. The result really shows with a fantastic world that works. With that world in place, Priest sets to work with her story. At the heart of the narrative is a story about a family, one who's been split apart by the Blight that was unleashed when Blue's "Incredible Bone-Shaking Drill Engine" ripped through part of the city. Forced out into the Outskirts, away from the Blight, people are left to their own devices. Briar and her son live their lives, but they are haunted by what had transpired before. Zeke, in particular, knows little about what had happened to his father and grandfather, and because of his mother's unwillingness to really address the problems of the past, he gets no answers from her. To find them, he ventures into the dead city to find the answers. What happens next is a sort of journey of understanding and rite of passage, where both characters must learn to adapt and accept certain things about themselves. Things are complicated when both discover that there's a lot more to the walled off portions of the city. An entire culture and society of survivors has sprung up in the sealed off buildings, where people are largely ruled by a Dr. Minnericht, who resembles Briar's former husband. This is another area where the book really shines, and that's the use of this dead city. I've long been fascinated by what happens to buildings and societies when they're left to die, and books such as World Without Us and various galleries of empty cities are things that I seek out. Her creation of her own sort of underworld, lost and forgotten by the world around it, is really neat, and while there are a couple of flaws here and there, it serves as a fantastic setting for her tale. Boneshaker does have its share of problems, from some of the caricatured characters, namely Dr. Minnericht, who is essentially posing as Briar's former husband throughout the story. Built up through most of the book, the actual character was a bit of a letdown, and his element of the story seemed rather forced in, as did a subplot about the Wall's inhabitants rising up against his rule. Zeke's characterization worked most of the time, but at points, his dialogue just annoyed me, and pulled me out of the story just a bit. In the end, though, these are minor gripes that didn't impact the overall story too much. Boneshaker proved to be a quick read for me, and it was well worth the impulse buy when I was in the bookstore the other day. With a fast-paced story, with plenty of exciting twists and turns, interesting characters and a fun story, set in a very fun world, I'm eagerly looking forward to the next installments out of the world that Priest has set in motion. This book is pure dynamite, and while I'm still rooting for The Windup Girl for the 2010 Hugo, this book is certainly deserving of the heaps of praise it's already garnered. This was a fun read, one that held me up at night, distracting my thoughts at work, waiting for my next fix. More books need to be just like Boneshaker: fun, exciting, thoughtful and interesting.

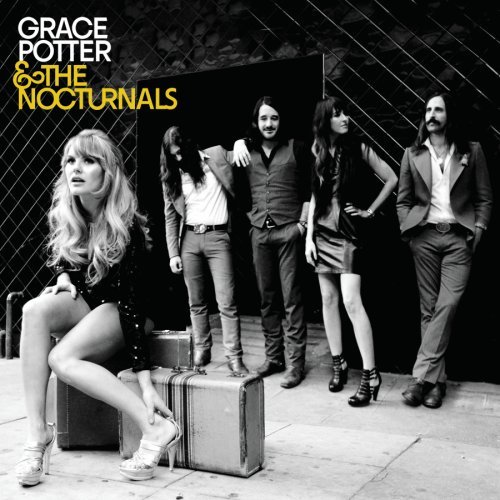

Grace Potter and the Nocturnals, the band's self-titled release jumps off a cliff with its opening track, Paris (Ooh La La), a remake of the hidden track If I Was from Paris from their prior album, This Is Somewhere. At least, that's what it feels like - a rush of adrenalin followed by fun beat that gets one moving to the song. With their fourth album, the Nocturnals have undergone some changes. Last year, the band lost its original bassist, Bryan Dondero over some creative differences, which in turn allowed the band to bring bass player Catherine Popper, as well as rhythm guitarist Benny Yurco.